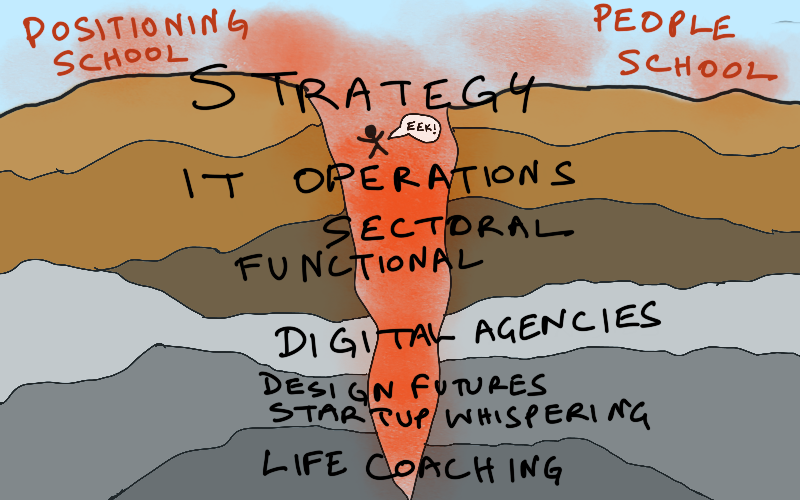

There is a fault line that runs through the consulting world. You can find it in every corner of it, from Fortune 100 strategy work and sector or function-specific work to startup-whispering and boutique design agency work.

You can even find it far from big organizations in domains like life coaching for stay-at-home housewives.

The fault line is live. It seems to propagate through completely new consulting domains as fast as they emerge.

This is the divide between the Positioning and People schools of consulting.

The essential difference between them is that the Positioning school takes its intellectual cues from economics, and uses formal models and numbers as the ultimate foundation for everything, while the People school takes its intellectual cues from sociology and psychology, and uses narrative as the ultimate foundation for everything.

If you think these big-picture schisms only matter at C-suite levels, for billion-dollar problems, think again. A life coach might adopt a spreadsheet-driven life optimization approach (this essay explains how you can do that) or one that looks more like psychoanalysis. Or take the newish field of crypto. The Bitcoin world is already exhibiting Positional school biases, while the Ethereum world is already exhibiting People school biases.

Why should you care?

You should care because great deal of energy has been building up along this fault line ever since the internet matured as an economic medium around 2000, destabilizing a 50-year old detente between these two schools. A detente that favored the Positioning school.

A war of ideas is coming, and you’re going to get caught up in it one way or another.

You should also care because because indie consulting is almost entirely People school. The converse is also true, though less strongly so: the People school is dominated by indie consultants (and smaller boutique agencies). So merely by identifying as a current or aspiring indie consultant, chances are, you’re at least unconsciously sympathetic to the governing philosophies of the People school, and unsympathetic to those of the Positioning school.

This means you’ve likely already picked a side, and it’s probably the People side.

Walter Kiechel’s excellent 2010 book, Lords of Strategy, has a good account of the history of the Positioning vs. People schism in the strategy consulting world, where the divide is clearest (here’s my review), so I won’t rehash that. Let’s skip right to the methodological differences between the two schools.

The Great Playbooks

This week’s application of the Bohr principle: The opposite of every Great Playbook is also a Great Playbook.

The Positioning school tries to operate by this Great Playbook:

-

Assume a relatively simple, predictable model of the players in a situation (example, rational actors, bounded rational actors, or legibly-biased rational actors).

-

Make some sort of standardized, relatively detailed, and data-driven map of the environment.

-

Place the simplified people models on the map.

-

Simulate possible futures, pick the best ones, and then use the player models to prescribe courses of action.

-

“Execute” the solution, and monitor the evolution of the situation with a feedback loop.

The People school tries to operate by this Great Playbook:

-

Take an inventory of actual named players in the situation, sorting them into rings by their level of agency and ability to influence the situation.

-

Make up a story to account for the recent history of the situation, using abductive reasoning, to uncover what the actual players are up to, and why.

-

Start “nudging” the situation to test your narrative, and start forming live, evolving judgments about the actual players: who matters, who doesn’t, how they align/don’t align, what futures they are working towards.

-

Pick the group of players you think is both right about the future, and capable of winning the future. Help them win. If such a group doesn’t exist, or you’re on the wrong side from them, exit the situation or switch sides.

-

Keep retelling the story and nudging the action according to the current narrative logic, monitoring the evolving situation for narrative violations and disruptions.

Of course, these are just broad predispositions. In practice, both schools muddy their own idealized playbooks a lot. Still, there is something like a grain to how problems get analyzed and solved by the two schools, an overall tendency. My playbook caricatures attempt to capture those dispositions and tendencies visible under actual case histories.

The reason there is usually a clear tendency one way or the other is that opposed Great Playbooks are based on opposed Great Truths, and people tend to swing towards one or the other.

The Great Truth of the Positioning school is that objective, external reality is everything, and subjective reality is just noise that gets in the way, but is easily tuned out.

The Great Truth of the People school is that subjective, internal realities (note the plural) are everything, and objective reality is a matter of evolving consensus and dissensus.

The resulting methodological divide between the schools is pretty unmistakeable.

The Methodological Divide

For the Positioning school, narratives, if used at all, are a matter of cosmetics and optics. A way to package, present, and influence using the conclusions of a one-size-fits-all playbook.

Positioning school practitioners are essentially wonks at heart, who believe in truth-by-spreadsheet, but sometimes make what they think of as concessions to human nature by telling stories.

For the People school, formal models and data, if used at all, are something like specialized forensic investigative tools. To be used when the process of repeatedly retelling the story while nudging it along runs into show-stopping mysteries and puzzles.

People school practitioners are essentially storytellers at heart, who believe in truth-by-narrative, but sometimes make what they think of as concessions to empiricist insecurities by including data and graphs.

These two Great Playbooks are in an eternal cosmic dance with each other.

It should be obvious that the former produces scalable, generalizable, somewhat universal solution templates for widespread problems, while the latter produces non-scalable, bespoke, hard-to-generalize solutions for specific situations.

Peak Positioning School

Great Truths are eternal and unfalsifiable. Great Playbooks never go away, they are simply rewritten for new eras through cycles of prominence and obscurity.

That doesn’t mean that all Great Truths are equally true at all times. When a Great Truth and its associated Great Playbook get too powerful, internal contradictions start to blow up. Then you get a collapse and recession, during which the opposed Great Truth rises from its own recession. So you have 2 yin-yang cycles of peaks and troughs.

The Positioning school has been on the ascendant for about 400 years, with a particularly rapid rise to near-total dominance in the second half of the 20th century. The People school, on the other hand, has been in recession for nearly as long, and is due for a resurgence.

Peak Positioning was probably sometime between 2001 and 2015. The output of the Positioning school has declined in quality if not quantity. It hasn’t had truly fresh big ideas to offer since the late 90s, and is running largely on momentum and fumes at this point.

The Lay of the Land

By my estimate, about 80% of the consulting industry (in terms of revenue and profits, but not headcount) is aligned formally or informally with the Positioning school.

It comprises relatively larger firms and institutions, including the Big 3 consulting firms (McKinsey, Bain, BCG), the Romulan Empire, and Mordor. It scales all the way down to firms of a couple of hundred. Many indie consultants who are alums of larger organizations also run the Positioning school playbook.

The heart of the Positioning world is Harvard Business School, and the Pope of sorts is Michael Porter. Other leading intellectuals of the Positioning school include Emperor Palpatine, and Saruman. Institutionally, it is organized as what Kiechel calls a literary-industrial complex, comprising prestigious publications, conferences, and a busy book-producing cottage industry to document the never ending stream of structuralist models of the world. Positioning School people wear expensive suits and fly around in business class.

The People school is much more of a fragmented grab-bag world of small firms and indie consultants. Instead of a single heart, it has a distributed presence all over the world, with small, volunteer-staffed outposts in Silicon Valley, the University of Toronto, and Tatooine. Instead of a Pope, it has dozens of contending thought leaders, such as Karl Weick, Gareth Morgan, Albus Dumbledore, Yoda, and Lao Tze.

Though we have a few of our people at Positioning School strongholds, such as Clay Christensen at Harvard, institutionally the People school world comprises a shadowy network of personal relationships, stealthy organizations such as the Order of the Yak, and a vast, hidden warren of emails lists, slacks, twitter conversations, and messaging groups. We typically wear Henleys, rarely fly business class, and often orienteer cross-country to get from Point A to Point B.

Instead of a literary-industrial complex, we have something more like a background tradition of evolving oral history with many more contending ideas and no clear canon at the core. To quote from my review of Kiechel’s book:

[Lords of Strategy] quotes one study which found that 105 experts polled for “key ideas” from the [People] school produced 146 candidates, of which 106 were unique. With that much dissent, the “People” school doesn’t stand a chance in the commercial marketplace for retail business ideas (which is why, by my reasoning, it is automatically more valuable, since fewer people understand the ideas). By contrast, in the “Positioning” school, there are perhaps a couple of dozen key ideas that everybody agrees are important, which every MBA learns, and most non-MBA managers eventually learn through osmosis.

I wrote that in 2010, when the tide was just starting to turn in favor of the People school (which Kiechel notes in his book).

Springtime is coming for the People school, and winter for the Positioning school. So congrats, you picked the right side at the right time.

Be wary though, of getting all tribal about it. Being a consultant is about staying in a state of dynamic balance, evolving your own game with the shifting balance of power between Great Truths and Great Playbooks.

The Positioning school may be headed for an extended recession, but there will still be times when its Great Truth will prevail.

The People school may be ascendant and headed for dominance in the post-digital world, but there will still be times when its Great Truth will fail.

Think of this as the difference between riding a bicycle and sailing a sailboat. A bicycle in a state of balance is upright except when taking corners. But a sailboat might lean strongly in one direction or the other, depending on the direction of the prevailing wind, and the direction you need to go.

As this war of ideas unfolds, you want to be a sailboat, not a bicycle.