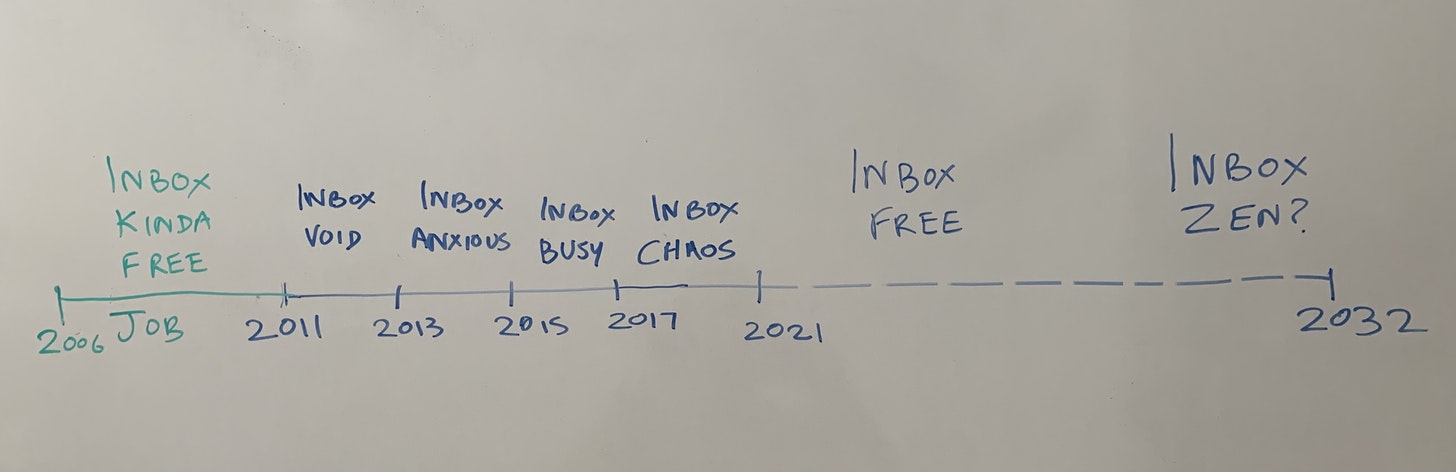

In the first three parts of my look at the evolution of the gig economy from my own 10-years-in perspective, I looked ±10 years at the 3 layers of the stack that I think of as forming the background canvas of our work: workflows, trust, and money.

In this part, I want to explore what I think of as the element between foreground and background: scenarios. Scenarios are how you imagine how evolving patterns in workflows, trust, and money coming together around big, external, non-economic forcing functions to form larger economic stories. These stories cannot be told in the form of a “view from nowhere.” They can only be told from a particular interested perspective: in our case, that of the indie consultant.

Looking out at the future is only a meaningful exercise if you look back at least as far in the past: after all scenarios that cannot even achieve consistency with the past have little hope of comprehending the future. And for telling big stories and positioning yourself within them, you have to look past the boundaries of your own chapter.

But to avoid getting trapped by a single story, you have to tell yourself multiple stories.

Four Stories

Here are 4 ways to look at the last 50 years of consulting, and corresponding ways of looking at the next 10 years. These 4 scenarios are very US-centric, but there will always be some bias in this sort of scenario construction, and US-centricity remains the best bias for telling any story of global significance. In the future, China-centricity might be the right way to develop scenarios, but we’re not there yet I think.

These are not meant to be great models of evocative storytelling, but as quick glosses of stories that seem implicit in the way significant clusters of people seem to think about indie consulting.

Story 1: A New Technocracy

Modern consulting emerged in the 1970s following the oil shocks and the rise of Japanese competition, making the MBA a sought-after degree. With deregulation, through the eighties and nineties, it continued to grow as an industry in prestige and influence, and came to be regarded as the main repository of business knowledge.

After 2000, the growth of the digital economy, and increasing perceptions of cronyism, corruption, and being out of touch began to slowly tarnish the reputation of the sector. The industry found it especially hard to make inroads into the emerging technology sector, which had a natural hostility to MBA-style consulting. Though it managed to establish a foothold, especially on the business side of the larger companies, it could not penetrate to the technological side, or down to the smaller startup scales, where much of the real action was.

Unlike in the old economy, big institutional consultants were essentially cut out of the most consequential conversations, even though they were able to access a large share of the available money. Talented young people in MBA programs read the writing on the wall, and increasingly began migrating directly to the heart of Silicon Valley, choosing to work in VC firms, directly for big companies, or even found startups. Others began migrating to Asia, establishing direct footholds and expertise in the Chinese sphere of influence.

In this environment, independent consulting began to take root, especially around boutique needs requiring deeper technical knowledge, alloyed with management experience in the new economy.

Over the next fifteen years, a large boutique industry of indie consultants emerged, offering expertise in every aspect of the new economy from SEO and growth hacking to product strategy and UX design, to database scaling and sourcing manufacturing in China. Blogs, newsletters, Twitter, and podcasts became the preferred source of business expertise, displacing traditional sources like consultant company reports, business books, or the Harvard Business Review. Private online forums began displacing old-style backroom conversations.

Through the Great Weirding (2015-20), the divide grew deeper, as the old consulting industry became increasingly out of touch, and the emerging indie sector gained credibility and professionalism rapidly.

In the next 10 years, the trend will continue, as indies organize more effectively to take on larger, more complex engagements, and offer more imaginative services at lower cost, with less focus on paper trails and manufactured justifications and more focus on fundamental problem solving. They will go beyond solo gigs to networked collaborations in larger teams.

As we head into an era defined by climate change, decarbonization, and deep reconstruction, indies will be critical to navigating events with agility and real problem-solving intelligence, since technology is the main lever for addressing the big challenges of the post-Covid world.

Sclerotic and cronyist consulting firms will be left behind and die along with the old economy they serve.

Story 2: A New Socialist Hope

Modern consulting emerged as a dark force in the 70s, as several decades of thoughtful and compassionate politics from FDR to LBJ drew to a close, and the ambitious social programs of the Great Society floundered during the Nixon administration.

An economy founded on treating workers well and fostering inclusive growth gave way to the rapacity of neoliberalism, marked by the greed of supply side economics, globalization, union-busting and deregulation. For a quarter of a century, traditional consulting served as the mercenary sword arm of capital, extracting an ever-greater share of profits from labor, and working with oligarchs and totalitarian regimes across the world to create and secure a global system of exploitation. Unions were busted, environmental and civil rights concerns were tossed aside, and sociopathic business leaders, supported by consultants, systematically stole the future from the people and made it the preserve of the 1%.

In this environment, indie consulting emerged as a boutique segment of individuals who combined highly valuable technological skills with a sense of integrity and ethics. Between 1992-2015, indies used the cheap and disruptive tools and technologies provided by the internet to gradually create and offer a systematic alternative to the corruption and cronyism of the old economy. At the same time, they pioneered a third way of work, rejecting both the role of neoliberal exploiter and exploited low-agency worker, to make their own way with dignity, using digital tools to asymmetric advantage.

Through the Great Weirding (2015-20), the contradictions of the neoliberal world order finally became unsustainable. And though Bernie Sanders did not win in 2020, the election of Joe Biden finally offers some hope for a new, more equitable future, and a return to dignity and prosperity for all has become possible.

In the next decade, indies will be at the forefront of a revitalized middle class and a socially aware and ethical response to climate change. Though unions are obsolete and beset by the same kinds of corruption that plague other neoliberal institutions, new kinds of collective action based on a new authenticity and post-capitalist modes of solidarity will emerge. Indies will be at the head of this movement.

A compassionate, socially conscious, networked workforce, supported by mechanisms like UBI and universal healthcare, will emerge to form the new backbone of the post-Covid decarbonizing economy.

Story 3: More Neoliberal Than Thou

Modern consulting emerged in the 1970s alongside fresh new ideas in economics and wealth creation. Thanks to the oil shocks and Japanese competition, moribund and inefficient American industry was shocked out of its complacency and forced to scramble to remain competitive. Decades of indulgent socialist policies had created a corrupt, bureaucratic, and inefficient economy with stagnant innovation, weak leadership, and a non-existent strategic culture.

Between 1980 and 2000, consulting played a critical role in making the American economy competitive, efficient, and innovative again, driving the greatest burst of wealth creation in history. It however, became a victim of its own success, growing complacent and corrupt in turn.

Indie consulting emerged alongside the internet as an agile, entrepreneurial, and effective alternative source of business knowledge and strategic capability that slowly began beating the traditional consulting world at its own game. Using the internet as a tool for asymmetric advantage, it slowly established itself as the go-to source of competitive advantage in the emerging tech industry. A new economy built on startups needed a new kind of consulting that was itself organized in startup-mode.

Through the Great Weirding (2015-20), the indie world finally came of age, with its own “passion economy” stack allowing it to compete sustainably. In the next decade, traditional consulting will recede and decline, and as the passion economy stack matures and grows, indies will grow along with it. Blockchain-based technologies will be especially important in this evolution.

The future will only have more and more post-industrial, post-capitalist weirdness and the unique challenges of climate change, which will not yield to business-as-usual thinking.

Indies will be at the forefront of helping the economy innovate its way through the challenges of a post-Covid decarbonizing economy with an entrepreneurial approach to big problems.

The traditional consulting industry, full of empty suits, may have started this game, but indie consultants, armed with just a laptop, internet connection, and blockchains, will finish it. The traditional consulting world will simply be unable to keep up in this accelerationist future.

Story 4: The Empire Strikes Back

Modern consulting emerged in the 1970s alongside monetarist economics and globalization. It was instrumental in creating the neoliberal world order and the great wealth that flowed from it.

When the internet economy emerged in the 2000s, the traditional consulting industry was initially caught flat-footed, but it learned rapidly and reinvented itself. It soon became an essential part of the new economy. In the first two decades, the tech sector had all the problems of emerging frontier economies. It was full of grifters and amateurs wielding outsize influence, and playing roles normally played by seasoned business veterans. Due to the small scale of much of the early-stage startup world, and the newness of the technologies being adopted rapidly, it took some time for the traditional consulting industry to catch up. But as the early tech companies grew into giant platforms that dominated the economy, consulting firms reinvented themselves for the digital age through acquisitions and building up of new tech practices. They successfully migrated from the old economy and established themselves as partners for the new economy, bringing much-needed professionalism and seriousness to the sector.

In the future, as tech matures and large companies continue to shape the future, the wild frontier of indie consultants and boutique operations will consolidate and become integrated with the traditional consulting industry. A new normal will emerge, leaving behind the anomalous dynamics of the Great Weirding (2015-20) will soon be a distant memory, like the Wild West.

As climate change and China increasingly become the priority for businesses post-Covid, the resources, scale, and deep global expertise of the the consulting industry will once more come to the fore. The wild west will be tamed, and deep expertise and institutional knowledge will come to be valued once again.

Eight Questions

Before we proceed, ask yourself these 8 questions:

-

Which scenario do you most resonate with?

-

Which one do you least resonate with?

-

What can you see with greater clarity through each story

-

What are the blindspots baked into each story?

-

What sort of indie is described by each story?

-

What sort of client is described by each story?

-

Which of these stories are best/least supported by known numbers?

-

What story threads do the available numbers not capture?

If you like, post your thoughts on these questions as comments below.

Now for some commentary.

Seeing Through Scenarios

In case it isn’t obvious, these 4 scenarios correspond roughly to the 4 quadrants of the well-known political compass:

-

Story 1, A New Technocracy is a Left Libertarian future

-

Story 2, A New Socialist Hope, is a Left Authoritarian future

-

Story 3, More Neoliberal Than Thou, is a Right Libertarian future

-

Story 4, The Empire Strikes Back, is a Right Authoritarian future

I’m probably hoping for Story 1 with some elements of Stories 3 and 2, perhaps an 70-20-10 mix, but that’s probably wishful thinking. I suspect the actual future will be about 10-20-5-30, for a total of 65%. I’d guess about 35% will be stuff nobody saw coming.

There are, of course, way more than 4 stories that can be told about the next ten years, and every way of reading the past leads to a way of reading the future. And every story offers its own way of grappling with known new elements in the landscape and unknown unknowns.

In this case, the new elements I incorporated are: Covid, China, Climate, and Crypto. The 4Cs of futurism today. They are not the only elements stories could or should be aware of, but scenario building is about making choices, since you only have so much room in a story.

The trick is to tell yourself many stories, and believe in all of them enough to become sensitized to the truths they uniquely apprehend, but be skeptical enough of all of them to avoid getting wishfully attached to, or blinded by, any of them. That is perhaps the best way to leave yourself open to the upsides of what nobody saw coming, and prepared against downsides that at least somebody saw coming.

Next week, for my 10th anniversary post, I plan to pull together this series with a grand finale exploring the most important question: what am I going to do with myself?