My ten-year anniversary as an indie consultant is coming up. On March 1, it will have been exactly 10 years since I quit my last job. It’s the longest I’ve ever been in any life situation as an adult. So I’ve decided to devote the next 4 issues of this newsletter to systematic reflection on the last 10 years, and to looking out at the next 10 years.

Let’s start on the base layer of the working life for everybody, whether in a job or an independent: workflows.

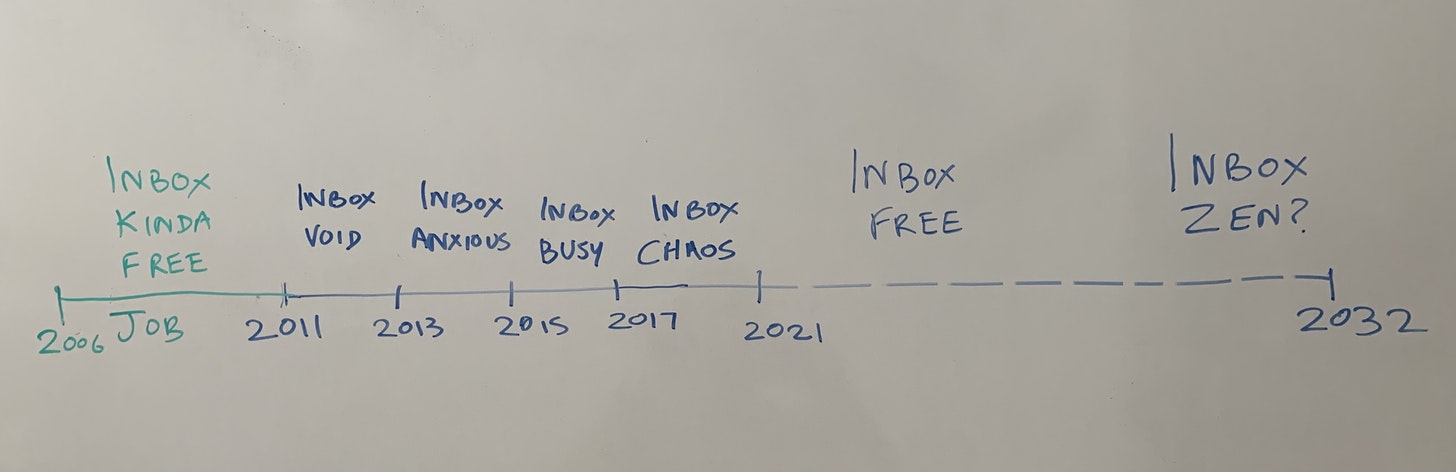

In this issue, I’m going to share a look back at how my workflow, more specifically my email inbox, has evolved over the last ten years since I quit my job. And look forward to how it might evolve in the next ten years.

This is a tale of 7 inbox conditions, marking a journey from my past workflows to my aspirational future workflows. Specifically, I want to take an inventory of the changing mental state induced by hitting Inbox Zero over the years (for the Gen Z among you, Inbox Zero is an idea most associated with David Allen’s famous GTD productivity system).

In theory, hitting Inbox Zero is supposed to make you feel mentally free, so it is an ideal best-case sampling point for your situation. How you feel when you hit Inbox Zero should reveal how free you really are.

Inbox Kinda-Free

This time, ten years ago, I had a job I had just decided to quit, leading R&D projects at Xerox.

In a job, once you’re above entry level, you’re typically on many email distribution lists. You are typically included in dozens of communication loops, whether or not you have any actionable responsibilities within them. You are expected to generally know what’s going on if you think you have — and want — a future in the company.

You have a manager and colleagues who expect specific things from you, but you’re also part of a larger corporate community that expects some general involvement from you, and gets generally involved with you in return. How you manage your involvement beyond immediate expectations is a function of your email game.

Back then, I used to be pretty disciplined about Inbox Zero.

In 2011, getting to Inbox Zero periodically with my work email, and enjoying a modest afternoon of clear-headedness every couple of weeks, was how I knew I was on top of things and at the right level of involvement with the corporate hive mind.

In the GTD philosophy, Inbox Zero is shorthand for the visceral experience of freedom. What I didn’t know then was that I hadn’t really experienced the intoxication of true Inbox Zero. Only a sort of low-alcohol-content ersatz version. As I now know, you cannot actually experience Inbox Zero at a job.

See, the thing is, at a job, your email is part of this river-like flow of the inner life of a business. Even if you happen to have nothing to do on a specific day, and are drifting between projects or bosses, you have an immersive situation awareness that you cannot turn off. Not even if you clear your inbox.

A nonzero fraction of your attention is locked up in the internal corporate stream of consciousness. Seeing, and being seen, in an open-ended way, within a shared situation awareness field, is how jobs work.

This is part of the definition of a full-time job — you commit to a mutual attention lock within the internal corporate stream of consciousness of an organization.

So even if you happen to achieve Inbox Zero at a job, in a decent-sized organization, your head never gets completely clear, because in a sense it’s not entirely your head to clear.

Inbox Zero amounts to Inbox Kinda-Free.

Your mind is not entirely your own to clear as you see fit. Other people have a certain right to peek into it and dump ambiguous things into it, generally via email (and these days via Slack and other media). A part of your head is devoted to, for want of a better term, “holding state” for the organization as a whole.

So you’re never quite free of and clear of the attention lock. Even if you hit Inbox Zero nominally, a part of your mind is always still “at work,” sharing in whatever sentiment superstate prevails in the organization at the time.

Inbox Void

On March 1, 2011, the day I left Xerox, that attention lock snapped free. And Inbox Kinda-Free turned into Inbox Void: the kind of emptiness it is terrifying to look into.

I no longer had my Xerox email account, and my Gmail was a desert.

Clearing it was trivial. But the clear state that resulted was not the Inbox Zero ideal of freedom. It wasn’t even kinda-free. Instead, it was a stark, oppressive emptiness that reminded me that I was not free. I was merely unemployed, and now newly burdened with figuring out how to make a living. My time wasn’t my own, but beholden to dollars I hadn’t yet figured out how to make, and clients I hadn’t yet landed.

Nobody needed me by default. It was no longer anybody’s job to check in on me and make sure I had enough to do. Or that I was getting paid enough to remain happy and productive.

The empty inbox was not a sign that I was on top of things, but a sign that I had nothing to get on top of, and that it was not actually a good state.

I didn’t need Inbox Zero. Inbox Zero was bad. I needed Inbox Busy. I needed a healthy flow of leads, inquiries, promising conversations for gigs, requests from clients, and so on. And I didn’t have it.

It took me perhaps another two years to get to there.

The interim was constantly stressful. The inbox would keep going to zero, with nothing to do, no leads to pursue, no obvious money-making options to simply exercise.

And there was no background stream of activity I could feel part of, to occupy my attention. At my job, even if I cleared my inbox on Sunday afternoon, I’d get up on Monday morning and face an inbox full of stuff to track, even if I was on top of my own stuff. It was like Twitter. The feed was always moving.

Early on, as an indie, I’d often clear my inbox, and it would stay clear of “work” email for days and sometimes weeks on end (not counting alerts, newsletters and personal email). Oppressively, stubbornly at zero even as the savings level slowly went down.

I’ll call this Inbox Void. A stressful kind of Inbox Zero that you don’t actually want. An empty state that oppresses rather than liberates, and can kill you if it persists long enough.

Inbox Anxious

It was probably sometime in late 2012, almost two years later, that for the very first time as an indie, getting to Inbox Zero became a non-trivial task again.

There was finally a there there to my consulting life. Enough going on in my email that getting to Inbox Zero meant doing some actual work. I had moved from Inbox Void to Inbox Anxious — activity tinged with ever-present financial uncertainty.

Multiple conversations were actually going places, email exchanges that could be called “work” were happening, contracts and NDAs were being sent back and forth. Hours were being billed, invoices were being sent out and paid (or not), context was being switched between clients.

I don’t remember the first time I had to handle two back-to-back meetings with different clients on the same day, and switch context on a dime, but at some point I noticed I was doing that sort of thing.

And suddenly it hit me: I’d gone from mostly faking it to kinda making it.

My indie consulting life felt real for the first time. It happened quickly, but not quickly enough that I noticed a sharp boundary. It wasn’t like a sudden switch being flipped.

But there was something new here. Unlike at a job, getting on top of consulting commitments and deliverables temporarily, and getting to Inbox Zero, felt different. Unlike at a job, there was no generalized background stream of corporate consciousness that would reassert itself and expand to occupy my mind via an attention lock.

This was a true zero. Once I got on top of things I owed clients, it was a kind of clear headspace with no background collective stream of consciousness at all. No attention lock within a hive mind.

But for the first few months, this state was fleeting and unstable. Impossible to sustain for more than a few minutes.

The thing is, even though there was no background stream of corporate consciousness to sink into, there was still the anxiety of insufficient gigflow, and too few leads turning into closed deals and signed contracts. Every time I hit send on the last thing I owed a client, and cleared the decks, the mild-to-medium anxiety (depending on cash runway) would flood right back in. And instead of enjoying “freedom,” I’d be thinking about how to drum up more work, or brainstorming other income streams.

This was what I call Inbox Anxious. Inbox Zero where the commitments have been cleared, but the anxiety has not, because you still haven’t acquired confidence in your ability to keep the gigs flowing. It’s better than Inbox Void, but hardly freedom.

You still haven’t learned to manage the stress of not knowing where your next billable hour will come from, or acquired the confidence that it will come, even if you don’t know from where. Part of you still itches to have a sure-fire plan for the next month’s rent. You haven’t yet shaken off the addiction to a predictable paycheck, to being needed-by-default by some large corporate consciousness.

Inbox Busy

Around late 2013 though, things began getting consistently busy enough, and I began trusting enough in things working out, that a new kind of Inbox Zero headspace became accessible.

I could turn around everything I owed clients, and I’d be in this intoxicating kind of clear headspace where I could feel really free. There was a real, reliable stream of ongoing activity to get away from — Inbox Busy — and I could actually meaningfully get away from it. Taking a busy inbox to zero meant actually being free rather than vaguely anxious.

Free of deliverables or paperwork I owed clients.

Free of background corporate streams of consciousness.

Free of immediate cash-flow anxieties.

It helped that my average savings level — or runway length — had slowly crept up over two years. The more runway you have, the more you can actually enjoy Inbox Zero when you get to it.

Initially, this kind of headspace was pretty rare. Maybe one afternoon every few months. Then I’d go through periods where I could hit that mood for an afternoon or so every week.

Those were fun times, but they didn’t last.

Between 2014 and 2017 or so, I suppose I went through some sort of consultant-market fit threshold, and almost without realizing it, landed in a condition where I typically had multiple active gigs going at any given time (right now I have 5 active gigs and 3 on the back burner), and getting to Inbox Zero started getting rarer and harder than it had been in my old job.

I had gone past being busy enough to being too busy (which is not the same thing as making too much money). I’d landed in the regime I’m in now: Inbox Chaos.

Inbox Chaos

In a single company, the corporate stream of consciousness has a sort of harmonized flow to it, so you can generally stabilize and zero-out all your active threads at once. And when you do, there is something it is like to simply be immersed in the corporate stream of consciousness. It has a direction and purpose, and an ongoing story that makes sense. For me, at Xerox, on afternoons I got to Inbox Zero, I’d land in a sort of generic Xerox headspace. I’d check in on other projects, chat with colleagues, catch up on intranet news, and generally partake of the Borg’s mind-state (or more technically, the egregore mind-state).

When dealing with multiple clients operating on very different tempos within unrelated stories, with corporate streams of consciousness in different moods, it is much harder to wrangle them all down to zero at the same time.

And when you do manage it, while you don’t have a single corporate stream of consciousness filling your head, you have this sense of being in the eye of a chaotic storm.

The thing is, the economy is a wild place, and once you’re plugged in enough to the wilderness directly via multiple varied connections, there is a sense in which you’re now immersed in the stream of consciousness of the economy as a whole.

The larger gestalt of macro forces and trends starts to seep into your consciousness. It’s not just the news. You’re not a spectator or an analyst writing trend reports from the comfort of a Gartner office. You embody the health of an economy, in the sense an indicator species embodies the health of an ecosystem.

But unlike a corporate (or even sectoral) stream of consciousness, there is nothing it is like to be in the general macroeconomic stream of consciousness. The economy, unlike a single corporation, is not an egregore or Borg-mind. There is no mind directing the invisible hand.

While more diffuse and incoherent, and more resistant to anthropocentric identification, this stream of macroeconomic consciousness is ultimately far more powerful than that inside any single company. Once you get sensitive to it, and open your mind to it, it will start to colonize your mind, unless you do something to stop it.

Sometime around 2017 I noticed that this was exactly what I was doing. I had almost unconsciously started cashing out some of the freedom of Inbox Zero moments (turned into hours and days), with the chaos held temporarily at bay, by indulging in several “freedom projects” of my own.

And that had workflow implications.

For example, I realized that I liked to save mornings for writing, and that I did not enjoy having to work on two different gigs on the same day. Back-to-back meetings with multiple clients, previously a sign of having made it, and a sort of badge of honor, now began to seem annoying and exhausting.

Almost without planning it, I started doing active load balancing, batch processing, and time management to create and maintain conditions favoring more frequent and extended Inbox Zero headspace. Hilariously enough, this was the reason I quit my job in the first place — to be able to do that. It just took me ten years after quitting to actually get there.

I was starting to identify and wall off small, fragile islands of actual freedom that I could inhabit during the more stable periods of Inbox Zero, protected from the chaos.

I began saying no more often to potential clients whose needs didn’t fit the workflow rhythms I wanted to create, preserve and protect. I began setting expectations with clients that created room for my own activities. I no longer promised aggressive turnarounds that would disrupt my own routines. Protecting islands of true freedom on my calendar began to seem more important than maximizing billable hours.

It wasn’t that I was making more money, but that I had begun to value time better. That, I think, is the beginning of getting to Inbox Free. When Inbox Zero actually feels like freedom, rather than some lesser thing.

Inbox Free to Inbox Zen

I hope where I am now is on the cusp between Inbox Chaos and Inbox Free. A state where I can periodically get to Inbox Zero, and stay predictably in a free-and-clear headspace long enough, and frequently enough, to make steady progress on my own “freedom projects.” I don’t care about maximizing revenue, and I don’t worry about “leaving money on the table.” So long as I’m making enough to pay for my life, and some savings, I’m mainly solving for freedom. It’s just taken me a decade to get to where that’s a meaningful problem with real solutions at the workflow level.

I still can’t reliably do something like block out entire weeks to make progress on some freedom project, like my much delayed science fiction novel, or the rover I am trying to build. But I can do an afternoon. And occasionally a whole day.

Progress!

Admittedly, Inbox Free seems like a distant goal now, but it no longer seems like an impossible utopia. The chaos overwhelms me more often than I am able to hold it at bay. But I’m getting slowly and steadily better at holding my own. I wouldn’t say I’m winning the battle against chaos. But I’m losing less often.

This does not happen automatically.

It takes work to create these chaos-beating conditions and maintain them. It takes cunning to turn Inbox Zero moments into Inbox Free afternoons or days. And they can be destabilized at any time by a bad quarter or year. By a gig falling through or a contract getting canceled.

Experience and a ten-year track record do not make you immune to the vagaries of the gig economy. Just because I’m a decade into the game does not mean I can’t hit a bad patch, and regress back to Inbox Anxious or Inbox Void.

But having been there before, and having climbed out more than once, I have a certain confidence in my ability to do so again. And again.

It’s not Sisyphean though. It’s more like a video game, where once you reach a certain level a couple of times, even if you get killed and have to respawn at Level 1, you know you can get back to the previous highest level again. You might even be able to speed-run there. And each time you return to your previous highest level, you have another shot at making it to a new level.

I don’t know what the next ten years hold for me. I am 46 now, and will be 56 then if I am still around. Maybe there are a few more Inbox Levels to discover with increasing levels of freedom. And maybe there’s even an end to the finite game of inboxes, when I can quit playing the high-stakes version, where I have to keep score and actively work the time-vs-money tradeoff curve.

Maybe I’ll hit the Zen mode of the game, where I’m playing to continue the game, rather than to win the current level.

One can hope.