One of the things free agents have to do is actively manage their psyches around work. In the paycheck economy, if you have a decent job, amateur psychology is mostly just an idle pastime built around comparing Myers-Briggs profiles for fun, and trash-talking people who score differently than you. If you’re otherwise mentally healthy and the job is not toxic, it is just harmless fun. The environment itself passively manages your psyche by being relatively stable.

But for free agents, managing your psyche can be a matter of life and death. Unhealthy attitudes can send you down a spiral of self-destruction no matter how strong your position. And healthy ones can transform even bad situations into strong positions.

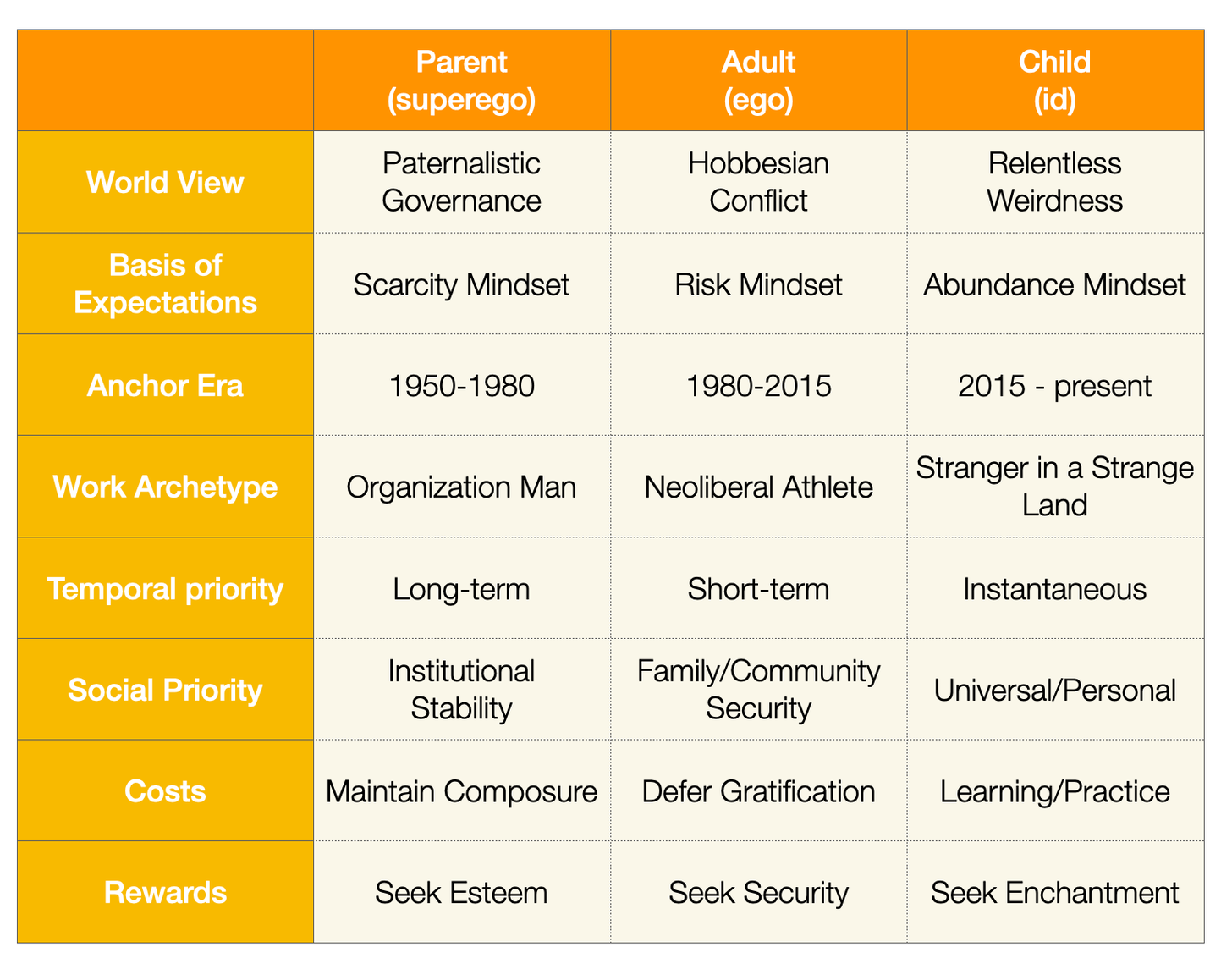

To help you reflect on how you manage your psyche, I made a table of what I think are the important dimensions free agents should periodically reflect on. I’ll explain the logic in a minute, but before you read on, just go down the rows of the table and identify whether your attitudes most align with the Parent, Adult, or Child column on each dimension. You don’t need to understand the underlying conceptual machinery to do this.

The table is based on conceptual machinery from one of my favorite DIY psychology frameworks: Transactional Analysis, or TA.

TA is a neo-Freudian approach to psychology, developed by Eric Berne, which was very popular in the Eighties. It was applied primarily to analysis of game-like behaviors in relationships (explained in Berne’s bestseller Games People Play), based on unbundling personality into Parent, Adult, and Child components (updates to Freud’s superego, ego, and id). The models were later extended to analysis of life scripts and postures (in Thomas Harris’ bestseller I’m Ok, You’re Ok).

While these basic uses of TA for game and script analysis are very useful for for the free-agent’s toolkit (client interactions are full of Bernean games), I want to suggest a different use: periodically recalibrating your relationship to the world.

Though I’ve drawn on TA models and frames to make the table above, you don’t need to be familiar with the conceptual machinery to use this table and draw conclusions from your responses.

Along the key dimensions in the table, how do you relate to the world?

-

Through your Parent, via internalized, unexamined societal attitudes and received wisdom?

-

Through your Adult, via conscious, reasonable, competent, reality-grounded behaviors?

-

Or through your Child, via playful, exploratory, fumbling, muddling, impulsive engagement of the world?

Paycheck employees in non-executive ranks typically have a strongly Parent-dominant life posture. Executives and more mercenary 80s/90s/00s style free agents typically have a strongly Adult-dominant life posture.

Neither is, I think, well adapted to the world we are heading into; the world that has been taking shape since 2015.

Strange though it might seem, a Child-dominant life posture is actually best suited for our current world, and is characteristic of both innovative entrepreneurs and free agents who thrive.

Why?

The Biggest Risk

The thing is, the biggest risk in the weird new world is neither long-term security (which Parent-dominant attitudes solve for) or short-term survivability (which Adult-dominant attitudes solve for). Those are important, of course, but moot if you become too disenchanted with the world to even get up in the morning and do something meaningful with your day.

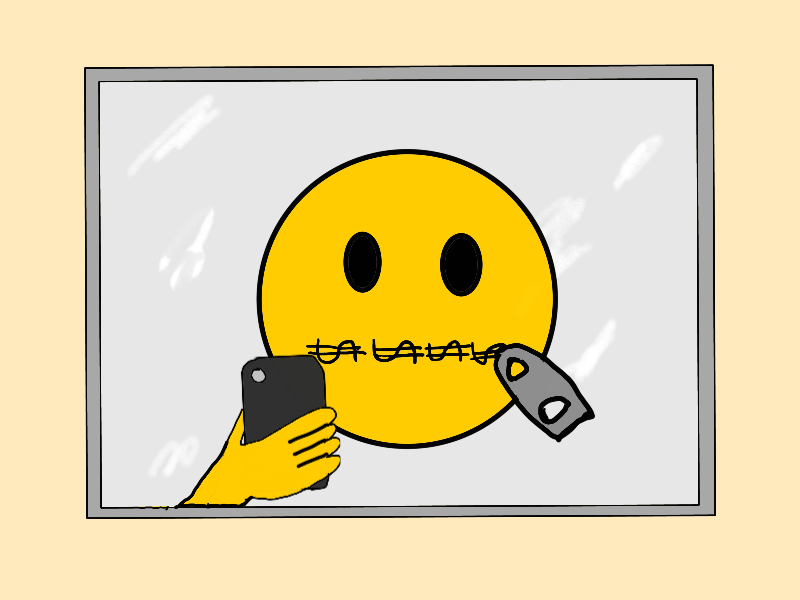

The greatest endemic risk to the psyche in 2021 is not that you’ll end up on the streets next week or fail to fund your retirement in 30 years. The greatest risk is that you’ll feel so relentlessly battered by the weirdness all around that you’ll go numb and simply disengage from the world entirely today.

Short and long-term security are moot if your life minute-to-minute is unlivable due to overwhelming weirdness. And your inner Parent and Adult have no clue how to handle the trauma of weirdness.

The evidence for this is all around us. Around the world, younger generations are reacting to coming of age (which is the same thing as reining in your Child and turning on your Adult and Parent) in a bleak world by retreating.

The Japanese phenomenon of hikkikomori is spreading. The risk of becoming so disenchanted with the world that you retreat into your parents’ basement is high. Ironic, huh? Giveupitis as the mark of growing up.

Some call this a meaning crisis. I’ve lately started thinking of it as an enchantment crisis. The primary reward your Child seeks in the world is an enchanted way of being in it. When this drive is starved, you get disenchanted, and even if your Adult remains competent at functioning in the world, and your Parent has all the right cliches on file for every situation, you lose the will to live. Because that will comes from the id, the Child.

This is becoming increasingly common. It is getting easier and easier to become terminally, fatally, disenchanted with the world and turn into one of the walking dead, a zombie assemblage of functional but pointless Adult/Parent drives, until one day you fall down and can’t get up again because you don’t want to.

See, the thing about the weirdness all around is:

-

Most Parent data (the superego is mostly data) has been undermined by recent historical developments. Your Parent is kinda out-of-touch (just as your actual parents likely are). Your hand-me-down cache of cliches to live by has been invalidated.

-

Most Adult skills (the ego in TA terms is mainly skills grounded in reason) have become overwhelmed by the sheer complexity and weirdness of our world. The formulas and algorithms don’t work. They’re thrashing. They’ve turned into delusions of competence. Adulting has turned into a non-functional LARP. That’s why you have to learn it like it’s a quaint retro hobby from 1955. If “Adulting” were actually life-critical, you’d be dead already.

-

But most Child tendencies (the id is mostly tendencies) are still pretty functional. Children are naturally present in the world as strangers in a strange land; alien beings suddenly dumped into relentless weirdness. Healthy children respond to weirdness with exploration and learning behaviors. They respond to felt incompetence with trial-and-error practice. Healthy children prioritize enchantment, not retirement funds. The worry about making this minute worth experiencing, not making rent.

Though it might seem insanely risky to let your Child lead, with your Adult and Parent biting their tongues and following, under the extreme weirding conditions of today, it’s actually the safest thing to do.

Dump the shaky preconceived notions of the Parent. Dump the flailing and delusions of competence of the Adult. Let the Child lead.

Pay Yourself First: Child Edition

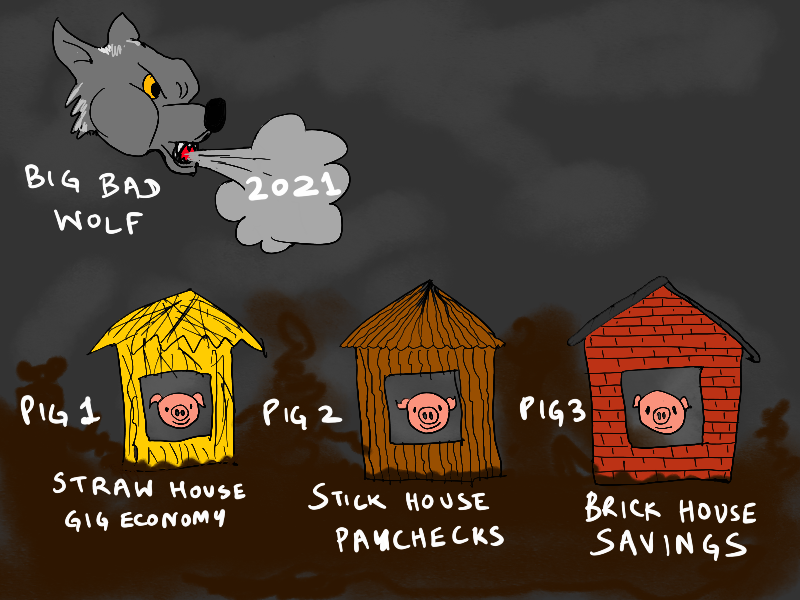

One way to operationalize this observation of the world is to reframe the classic personal finance advice, pay yourself first.

In the traditional form, the advice means paying into retirement savings before budgeting discretionary expenses.

This is classic Parent-dominant advice: long-term oriented, prioritizing social stability (of institutions that underwrite old age for all), etc. It is about saving money for future-you, while trusting that society will endure, and doing your part to make sure it does.

Between 1980-2015, this advice turned into a more Adult-dominant idea with emphasis on short-term risk management, winning in a Hobbesian neoliberal environment, and making sure your retirement was funded even if the world threatened to fall apart by the time you turned 65. It was a kind of Neoliberal Athletics competition.

But how are you supposed to pay yourself first when you are a NINJA? No income, no job or assets? Forget the defined-benefit pensions or lifetime employment of the 70s. You can’t even bet on the defined-contribution (employer-matching) or short-term stable jobs of 1980-2015.

To center the primary risk — of terminally disenchanted retreat from the world — I think of pay yourself first as being about the present-moment you, and in terms of time rather than money.

Pay yourself first in 2021 means prioritizing time for some activity that keeps you positively engaged in the world, through some enchanted mode of seeing, being, and doing that resists disenchantment and retreat to basement fantasies and LARPs. You only retreat to live in a video game world when you can’t find a way to participating in the enchantment available in the real world, no matter how weird such participation looks to traditionalists.

Pay yourself first in 2021 means aggressively nurturing and defending your primary mode of enchanted engagement with the world, even if it means forgoing some money in order to buy yourself the time to do so (something I’ve done very frequently).

Everyday Alchemy

I call this transactional enchantment both as a hat-tip to the Transactional Analysis frame that inspired it, and to point to the idea of trying to bring an enchanted perspective to everything you do, whether it is drafting an invoice, looking for gigs on Twitter, or writing a newsletter.

Enchantment is not just for game nights with friends, or whatever traditional or New Age spirituality you favor. Or something to relegate to hobbies, fiction-reading and TV-watching. It is something to infuse into everything you do.

It’s not about magic or woo. It’s about transacting with the world in a way that makes life not merely possible to live (whether in the long or short term) but worth living minute-to-minute.

What’s the point of short and long-term security if every day you wake up wishing you could just stay in bed, numbly withdrawn from the world, swaddled in blankets?

What’s the point of contributing to retirement savings if, like Bartleby the Scrivener in Melville’s short story, your attitude towards work has degenerated to “I would prefer not to,” and you’re one step away from terminal catatonia?

My own mode of transactional enchantment has been writing. Through good and bad times, cash-flow crises and flush periods, painful gigs and fun gigs, I’ve never stopped writing. I was writing through the euphoria of 1997-99, and I was writing through the Global Financial Crisis. I was writing through the halcyon GFC-recovery years of the early 2010s, and I was writing through the PTSD of the Great Weirding.

Everything I do is informed by my writing, and everything I do feeds into it. It’s where I transform the banalities of my day-to-day activities into an experience of life worth living. It’s my way of staying on top of the everyday alchemy that you simply cannot afford to get behind on. The disenchanted life is not worth living.

Writing is not the only way to achieve this kind of transactional enchantment, but it is one of the most accessible ways. It demands the least in terms of special talents. You don’t need to be artistic, musical, or good at programming to do it.

Just pick your mode (or rather, let it pick you). It’s the enchantment mode of being in the world that matters, not the medium.

If you fail at this absolutely basic housekeeping task of generating transactional enchantment in your life, minute-to-minute — literally Child’s play — everything else is moot. Your retirement fund won’t save your sanity, and LARPing Aurelian stoicism (a popular genre of Adulting) won’t make life worth living.

So pay yourself first. Make the time to stay transactionally enchanted with the world. Otherwise it’s game over.