For a while now, several of my fellow indie consultants have been asking me to share more details about executive sparring, a style of 1:1 consulting that I’ve been developing and practicing for almost a decade now. Before I get into it, I recommend watching this short video of Mike Tyson, at age 53, sparring with his trainer, to get a visceral sense of what I’m going to be talking about.

Yes, at their most intense, executive sparring sessions can feel like the intellectual equivalent of this. Not all sessions are this intense, or this combative, but the most valuable ones — both for me and for the client — are.

Like the sparring partner in this video, an executive sparring partner would not last very long in the ring in an actual competitive bout with a high-functioning executive client. Yet a good sparring partner can provide a great deal of value in a non-bout sparring session.

At this point, I’ve worked as a sparring partner with several dozen senior executive clients (some of them for years) in organizations ranging from startup scale to Fortune 100 corporations, and across half a dozen industries. Sparring work now constitutes almost the entirety of my consulting practice. It’s a fairly demanding and intensive kind of highly personalized 1:1 support work, and is neither cheap, nor very scalable. So unlike things like training workshops, or process/capability consulting, it’s not the kind of thing you can offer at scale. You’re not going to rack up hundreds or thousands of clients in a few years. You’re not going to be sparring with an auditorium-scale audience. Writing a book about your business ideas won’t make it any more efficient. You’re not going to be automating any of it.

I estimate that a good sparring partner can support no more than half a dozen active clients in any given month without burning out. And it typically takes half a dozen meetings of 60-90 minutes across six months or so for the sessions to become truly high-value.

Most importantly, though you might be able to bill at a high rate, due to the individualized, automation-resistant, time-intensive nature of it, you’re not going to get mega-rich doing it. Sparring is an artisanal kind of consulting. You can make a decent living from it, but if you’re solving for big money from a 4-hour work week, you should look to a different kind of consulting business model.

Teaching Sparring

Earlier this week, after conducting a first informal sparring workshop for a few friends, I decided I was finally ready to write about it.

While this series is primarily going to be for consultants who want to do this for money, it should also be of value to executives, since a significant part of being a leader is serving as sparring partner to peer executives and senior reports. In fact, most sparring happens among peers within organizations or industries. Executives hire people like me mostly when they cannot find suitable sparring partners within their own organizations or its immediate institutional neighborhood — which is as it should be.

Sparring is primarily valuable for senior executives who have already risen through the ranks of individual contribution and middle management (though that journey can happen surprisingly fast in startup environments), and is an alternative to the default style of working 1:1 with executives, which is generally called coaching. Unlike in sports, the two are hard to combine for reasons I’ll get to.

A question I’ve wondered about over the years is: can sparring skills be taught, assuming a broadly suitable temperament and an aptitude for it?

I’ve been at it for 9 years, and it probably took me 3 years to get it to consistently good enough that I felt I could do it with almost anybody. Can that learning curve be shortened?

Yes and no.

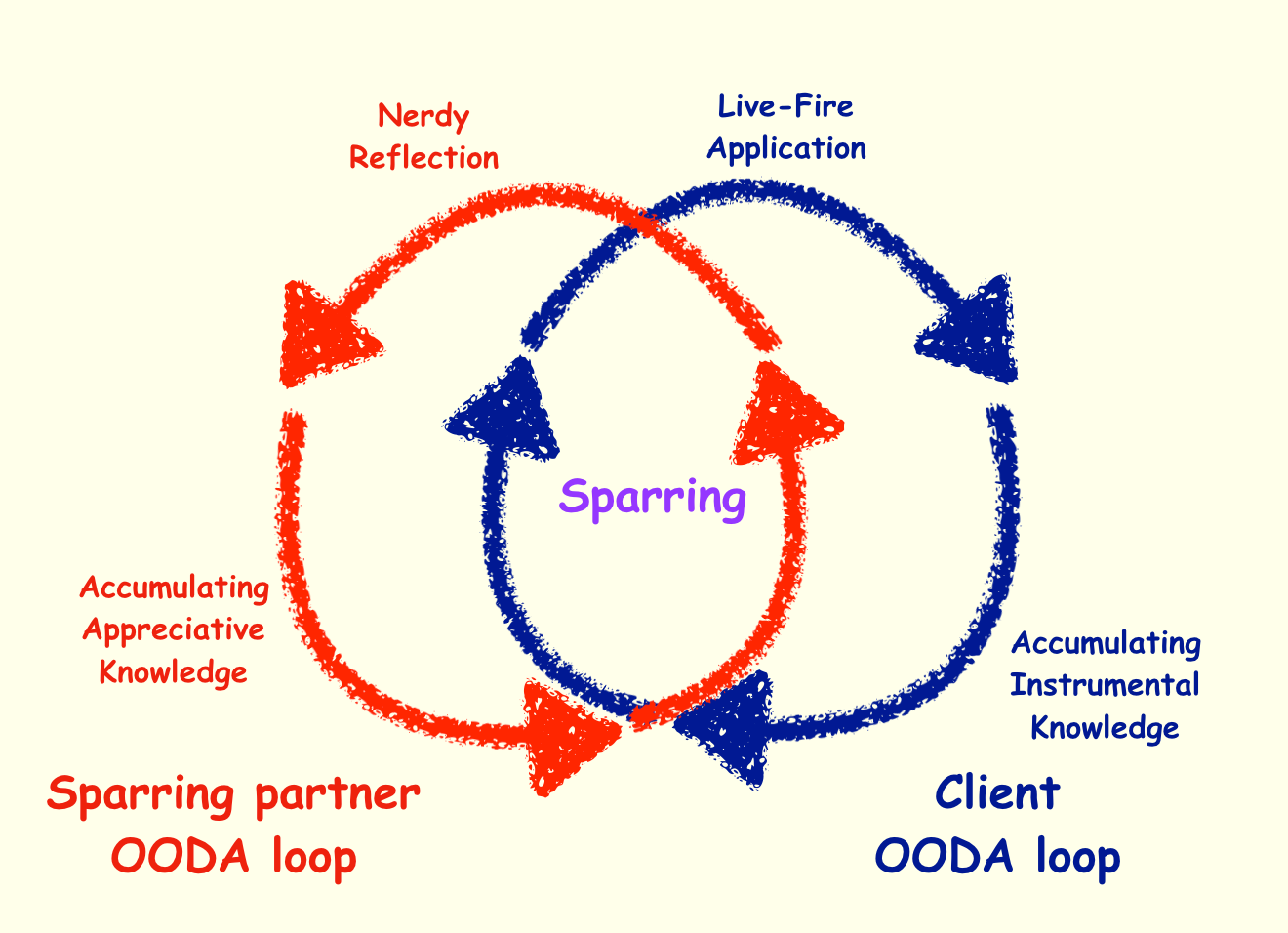

Some aspects of the skill-acquisition can be speeded up. Some things that took me years to figure out, I can probably teach in a day or two. But other elements of getting ready for the role — like reading widely and deeply about technology and business to develop an appreciative worldview of it (a sparring Weltanschauung if you will) took me decades (I’ve been reading business and technology books since I was a teenager), and I don’t think can be speeded up. I think will take anyone decades.

Fortunately, if you’re interested in developing sparring skills at all, you’ve probably already been doing the right kind of preparation anyway for other reasons, including plain curiosity. So you’re probably more prepared than you realize. It’s a question of recognizing the significance of what you’ve been doing, wax on, wax off style. But you’re probably not as prepared as you need to be.

In the pilot workshop a few days ago, I finally got a chance to try and explain and demonstrate the model to a small group of six willing guinea pigs via a small workshop. The participants were six indie consultants like myself, most of whom already had significant experience working with senior executives in a similar mode, but wanted to refine their practice and understanding of it, and make it more legible to themselves, to be able to continuously improve their practice.

The pilot workshop worked well enough that I decided this idea is actually in a teachable state, so I’m probably going to offer an improved version of it in the future, but before I do that, I decided I need to write up some of the core ideas.

So this is the first in a series of what I expect will be 4-5 newsletters covering the core ideas of sparring (the rest of the series is going to be paywalled though 😈).

In this introductory part, I want to do three things:

-

Define sparring

-

Distinguish it from other 1:1 relational practices like coaching

-

Situate it in the broader context of executive development

In the rest of this series, I will work through how to actually develop sparring partner skills, and a consulting business based on those skills.

Sparring as Live Theorizing

The goal of sparring is simple: to improve the quality of live theorizing executives do around their ongoing work.

The central insight driving the practice of sparring is that busy executives typically do not have time to do more than dip into fully formed theories of management or leadership, delivered through books, or executive education. Even the “case method” MBA students learn, which rests on live conversation/debate in groups, is too far removed from actual live situations to serve the purpose.

If you’ve ever read an HBR case study, you’ve probably had that uncanny sensation of looking at the business problem-solving equivalent of stock photography. A lot of fresh MBAs, who earned their degree perhaps too early, come across that way to me when they talk. They come across as smart, prepared, and with interesting things to say, but fundamentally lacking in serious exposure to live-fire, high-stakes executive decision making.

For strong executives, theorizing happens in a rough-and-ready form in the context of live action, working out how to act in, or respond to, specific situations unfolding now, involving specific people, constraints, and timelines.

Weak executives, by contrast, often come across as eager to avoid, sidestep, or ignore the hardest parts of the situations they are being paid the big bucks to handle. Much of their thinking happens on the sidelines, around situations that might unfold. Often their theorizing is too polished and refined — a dead giveaway that they’re far from the live-fire action.

Consider the analogous situation in boxing. A top boxer might study videos of an opponent for an upcoming title fight with their trainer, form a hypothesis about their weaknesses, and “workshop” bout strategies for that specific upcoming bout with a sparring partner. For example, Muhammad Ali famously did exactly that in preparing for his Rumble in the Jungle bout against George Foreman, abandoning the “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” style he was famous for, and adopting a “rope-a-dope” style designed to wear out Foreman. Wikipedia describes how that came about:

According to photographer George Kalinsky, Ali had an unusual way of conducting his sparring sessions, where he had his sparring partner hit him, which he felt “was his way of being able to take punishment in the belly”. Kalinsky told him: “Do what you do in a training session: Act like a dope on the ropes.” Ali then replied: “So, you want me to be a rope-a-dope?”

According to Angelo Dundee, Kalinsky told Ali: “Why don’t you try something like that? Sort of a dope on the ropes, letting Foreman swing away but, like in the picture, hit nothing but air.” The publicist John Condon popularized the phrase “rope-a-dope”.

If this anecdote is accurate, than Ali’s intellectual sparring partner, as opposed to the one in the ring, was the photographer Kalinsky. It’s weird how often this is how it ends up working. You might talk for hours, but in the end, it’s one casual phrase or thought that ends up unlocking the critical idea. My very first client said as much to me — that after twenty hours of chatting, the value I delivered all came out of one phrase I happened to drop casually in thinking through a problem: “penny auction.” Two seconds in twenty hours.

That pattern has repeated for nine years. Hours and hours of conversation and emails, punctuated by scattered moments of high-leverage usable insight — a phrase here, a 2×2 there, a particular quote or metaphor that fits the situation. It used to frustrate me a lot initially. Was there no way to cut out all the hours and just formulaically arrive at just those moments of insight? So far I haven’t found one. You have to put in the time — and learn to enjoy it.

Insights like this cannot be found in textbooks, cranked out of fully-formed theories, or by “solving” cartoon case studies in a classroom setting (the equivalent of a punching bag or boxing dummy). They can only emerge through the process of preparing mindfully for specific live-fire challenges with a live sparring partner who can keep up with you.

Like good boxers, good executives instinctively seem to follow a similar, highly situational preparation regimen. They typically study developing situations that require action (many even like the “review the game tape” metaphor), form one or more working hypotheses about how to tackle them, and “workshop” them with trusted partners before actually trying them “in production” so to speak. At any given time, they are shepherding a dozen situations along towards resolution, and workshopping multiple ideas about what to do, often with multiple sparring partners.

This short passage from a classic paper by Karl Weick, What Theory is Not, Theorizing Is, gets at the essence:

Products of the theorizing process seldom emerge as full-blown theories, which means that most of what passes for theory in organizational studies consists of approximations. Although these approximations vary in their generality, few of them take the form of strong theory, and most of them can be read as texts created “in lieu of” strong theories. These substitutes for theory may result from lazy theorizing in which people try to graft theory onto stark sets of data. But they may also represent interim struggles in which people intentionally inch towards stronger theories. The products of laziness and intense struggles may look the same and consist of references, data, lists, diagrams, and hypotheses. To label these five as “not theory” makes sense if the problem is laziness and incompetence. But ruling out those same five may slow inquiry if the problem is theoretical development still in its early stages.

I quote this passage on my own consulting website and describe sparring in relation to it as follows:

The bulk of my practice comprises 1:1 work with senior executives as a conversational sparring partner, to stress test and improve the rigor and quality of their ongoing thinking about their evolving challenges.

Of course, executive work is not boxing. Meeting rooms are not boxing rings (though they can sometimes feel that way). Purposes in organizations are generally more aligned, non-zero-sum, and non-adversarial than in a boxing ring. The preparation is much more of an intellectual process.

But many of the challenges of preparation are very similar.

Who Can Spar?

The executive sparring partner role is a relatively new kind of external consulting role for a simple reason — the kind of immersive shared context required between client and sparring partner could not exist 30 years ago, due to the sheer difficulty of creating the shared knowledge environment in pre-digital environments. This means, historically, the role has almost always been played by trusted insiders and colleagues rather than paid outsiders.

Usually, executives spar with trusted peers who understand the industry well enough to keep up. Common sparring partners include:

-

An executive in another company in an adjacent non-competing business.

-

A board member, key investor, or a retired executive from the same organization.

-

An academic studying the industry or domain (rare).

-

A peer executive in the same company.

That last option is less common than you’d expect. Conflicts of interest often prevent direct peers from serving as sparring partners for each other, despite being the best suited for it in other ways. Peer executives are often competing with each other for power, influence, and control over specific situations, so mutual sparring support is limited to windows of opportunity when they are not striving at cross-purposes.

Despite these problems, peer-to-peer sparring still constitutes the vast bulk of sparring going on in the world, simply because of the numbers involved. It is just a highly unpredictable and unreliable source of sparring support. If an executive relies solely on peers for sparring support, they may find it unavailable just when they most need it.

Basically, it is surprisingly hard for senior executives to find the combination of three key required traits in one reliably available person:

-

Sufficient domain knowledge to allow shared thinking in insider-language

-

Absence of conflicts of interest and misalignments that get in the way of trust

-

Intellectual capacity to process at the typically demanding level

In the past, these three requirements often ended up forming a pick-2-of-3 triangle in a field comprising only insider candidates. But on the other hand, outsiders typically faced far too high a barrier of acquiring enough insider knowledge to play the role.

Until the internet happened.

The Internet as Sparring Arena

Thanks to the internet, it is possible for vast numbers of people who are technically “outsiders” to keep up with an industry or a specific company from the outside, participate in lively discourses around it, and be generally informed and prepared enough to play sparring partner roles.

In 2020, often all it takes to form a surprisingly deep and useful mental model of an organization is a few hours spent on Google, LinkedIn, Glassdoor, Wikipedia, and social media. Throw in a phone call or email or two, and you are probably 80% of the way there even before signing an NDA and being given a peek at internal information.

And you do not need limited, narrow and expensive subscriptions to business intelligence/dossier services to do so. Most of the valuable situation awareness information is free.

Add to that the trend towards increasing openness — many executives openly discussing their challenges on Twitter among other things — and the set of potential sparring partners available to any executive vastly expand. In fact, many seem to show up on Twitter to do exactly that — free sparring sessions with random members of the public!

If you’re an executive at a small, cash-starved startup and cannot afford to pay for a sparring partner, I highly recommend this approach. To the extent you can, just blog or tweet publicly about your work, and you’re very likely to find the sparring you need for free.

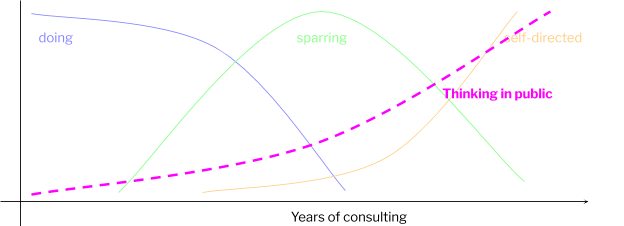

And if you’re looking to get into the business of being a sparring partner, there’s no better training ground than Twitter. You can literally try to provoke and engage thousands of executives. You’re very likely to get your first clients that way. I got my first couple of clients via Quora, and almost all the rest through some social media outlet or the other — Twitter, my own blog, contributions to industry blogs, and so on.

But information availability, while necessary, is not sufficient. Being a sparring partner calls for a particular temperament and personality (not learnable), and a particular mode of being attuned to others (learnable).

Sparring Partner as an Archetype

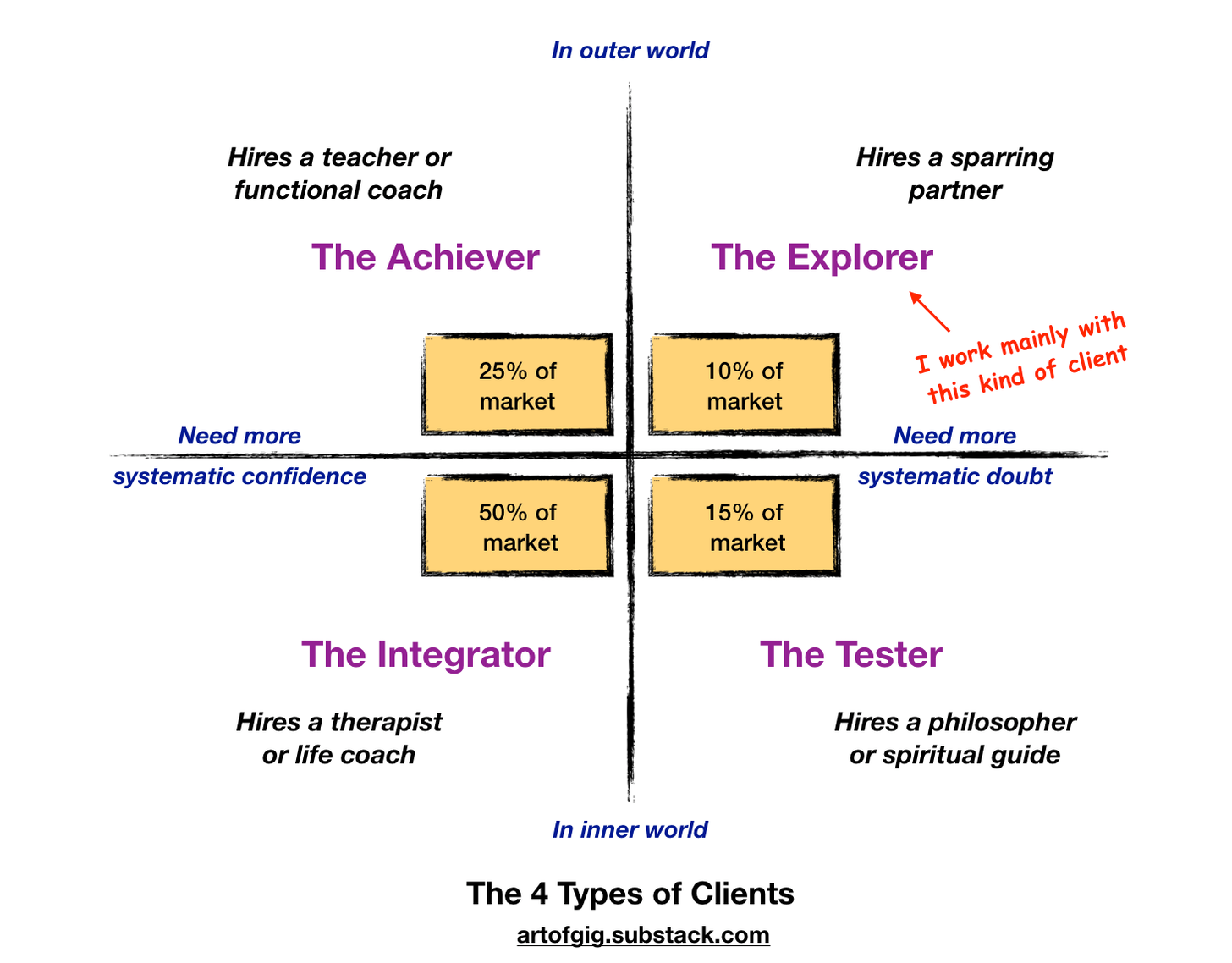

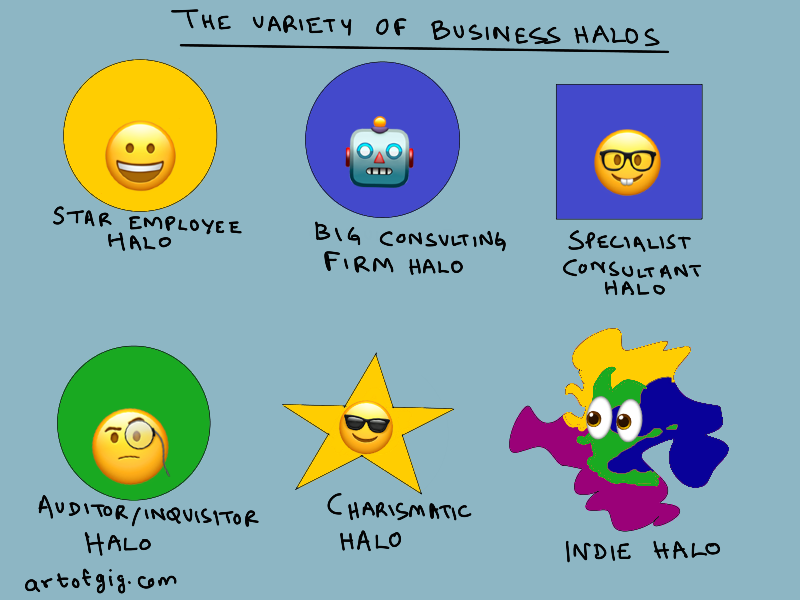

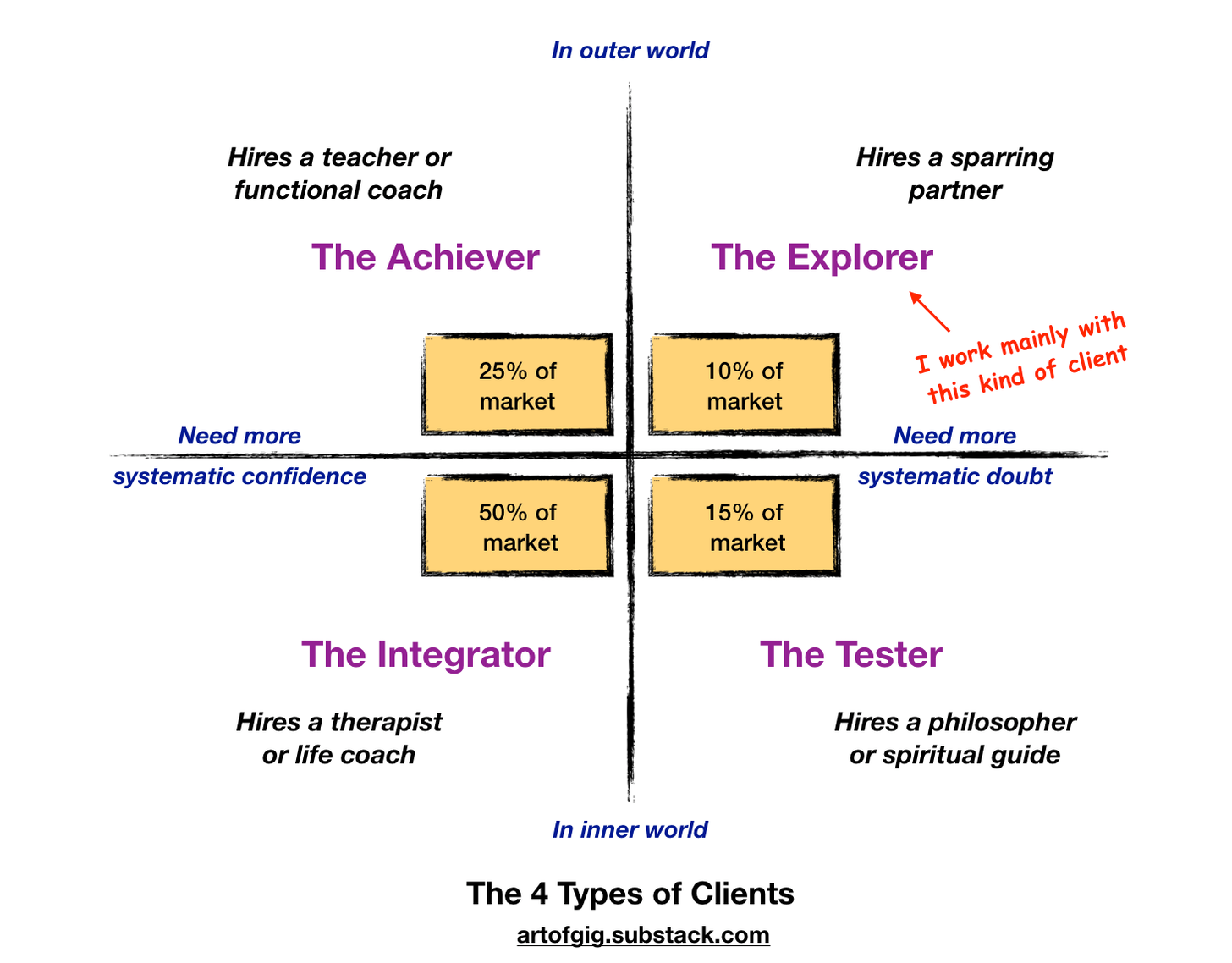

I’ve previously written about the idea of consultants as a well-defined archetype — shadows. This is particularly true of sparring partners. I also previously wrote about elements of consulting style, and offered this 2×2 of 4 types of 1:1 consulting roles, corresponding to 4 types of clients. While most clients are a mix of the 4 types (achiever, integrator, tester, explorer), most consultants, in my experience, can typically only serve in only one of these roles well.

Let’s get at the elements of the sparring partner archetype (both innate and learnable) via comparisons with the other 3.

-

Unlike a therapist or life coach, a sparring partner does not support inner work except occasionally as a side effect. Psychological insight into human nature is helpful, but not central to effective sparring.

-

Unlike philosophical counselors or mentors, the sparring partner does not occupy the position of a respected elder guiding an executive through inner or outer challenges they themselves have already been through. Your own banked growth experiences are helpful, but not central, to effective sparring.

-

Unlike an executive coach or teacher, the sparring partner does not support general-purpose behavioral development (forming good habits, losing bad ones, developing specific skills), in areas like productivity, emotional self-regulation, or “crucial conversations”. Behavioral insight is helpful, but not central.

What is central to effective sparring partnerships is actual understanding of the business domain and organizational environment itself. Having access to the enabling background knowledge is one half of the problem — largely solved by the internet. But actually being able to think on your feet with that knowledge is a different matter altogether, and the other half of the problem. One most people will fail at.

Often, this is a matter of the sparring partner having enough relevant career experience. People in classic “coaching” roles usually do not — they often have backgrounds in helping professions/fields like psychology, social work, or HR, but rarely in the fields where executives tend to emerge.

Most executives typically have career backgrounds (if not educational) in technology, finance, sales, or marketing, and are facing deep problems in those functional line-management domains. They usually need sparring partners who have at least a passing familiarity with the domains their work touches.

CEOs typically face problems that transcend even those functional domain boundaries and require knowledge going beyond, in that nebulous pile of backstopping activity that is “leadership”. They require sparring partners with domain/function experience and something more — a sort of philosophical fit of sparring styles.

This requirements makes “casting” for sparring roles much harder than for executive coaching roles, and it’s not a problem that can be solved by credentialing.

Executives typically know they’re not looking for traditional executive coaching, but can’t quite put a finger on what they are looking for. But they can recognize it when they see it.

Casting for Sparring

Much of the challenge of being cast in the role of a sparring partner is being visible in the right places when/where executives are looking for sparring support. That will be a topic for a future episode of this series, but let’s talk about how the casting process works.

Executives seeking sparring support often unconsciously look for sparring partners they can talk to in their own language, without having to constantly explain themselves, dumb themselves down, or having to provide quick tutorials on basic working concepts at every conversational turn.

They might provide a few pointers to learning resources, if they really want to work with you, but even that is rare. In general, they will expect you to learn enough to spar with them effectively in the very first hour. As a rule of thumb, if an executive has to spend more than half the time in the first hour of a sparring engagement explaining basic background ideas (especially basic technical concepts or basic business ideas like how to read a balance sheet), it’s not going to work out.

The ideal sparring partner is someone who already has a sense of the history of the industry and its technological foundations, has some functional depth in all the important domains the executive has to deal with, and has already been thinking about the latest fads doing the rounds.

The ideal sparring partner already has an opinionated take on important questions that are at least wrong (rather than not-even-wrong, which is the most common state), based on having kept up with the industry in question.

How do I know this? I know this because my clients have disproportionately been technology leaders, either leading technology/engineering functions, or having risen to CEO-level general roles from the technology leadership side. And this is not an accident. It is because I’m an engineer by training myself, and much of my writing and social media presence is suffused with technology references, metaphors, analogies, and historical anecdotes.

For a technology leader who reads one of my blog posts or a twitter thread, it is immediately obvious that it won’t take me painfully long to get sufficiently up to speed to serve as a useful sparring partner. I’m not going to be asking a machine learning company CEO what an eigenvalue is. I am not going to be terminally befuddled by a chemical industry CEO mentioning the ring structure of Benzene. Or by a CFO talking about gross margins and EBIDTA.

I’ll say more about this knowledge preparedness aspect later in this series, but make no mistake — sparring is a knowledge-intensive role. You have to know a lot, and showcase what you know, just to get in the game. And you have to be willing to learn a lot, very rapidly and efficiently, at short notice, to stay in the game.

If you have the temperament you’ll already know it. You probably read widely outside your field, and fairly deeply. You keep up with industry level trends in one or more large sectors at a play-by-play level. You keep up with science and technology news, at more than a casual level. You can parse at least half of any casual insider conversation you might hear about any industry in a coffee shop, and three quarters if you’re given a few minutes to google stuff (this is a game I used to play with myself a lot in coffee shops, back in the beforetimes when sitting around in coffee shops was a thing).

You don’t get there overnight of course. It takes years of being interested in business and technology and keeping up. But fortunately, it’s not a specialized kind of interest or attention. Whatever your reasons for your past interest and curiosity in business and technology, the fruits are going to be valuable in a sparring role.

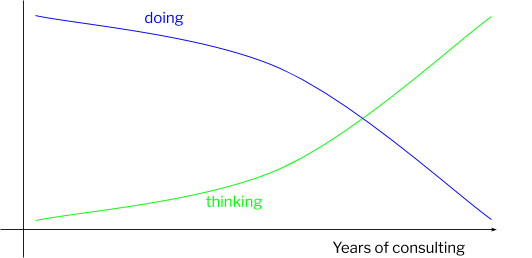

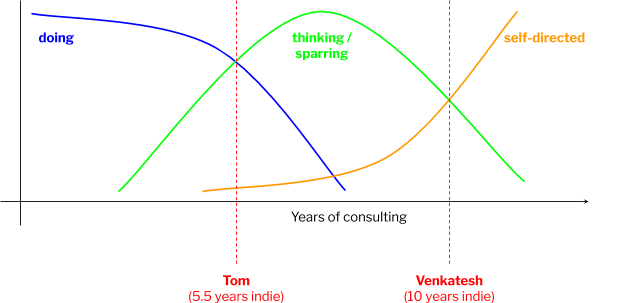

Sparring in Executive Development

Let me wrap up this looong first part by placing sparring partners in the context of executive development more broadly. The short version is this: there is no element of sparring anywhere in the typical executive development offering suite, which is why I have an indie career at all.

The traditional executive coaching model does not work for sparring, because most coaches do not have the right background to serve as sparring partners. Other elements of the leadership development world do not address the need either. People in that world do acknowledge the need, but generally leave it alone as an area to be covered by mutual peer-to-peer support. Which also does not work great for reasons I’ve already pointed out.

The slightly longer version.

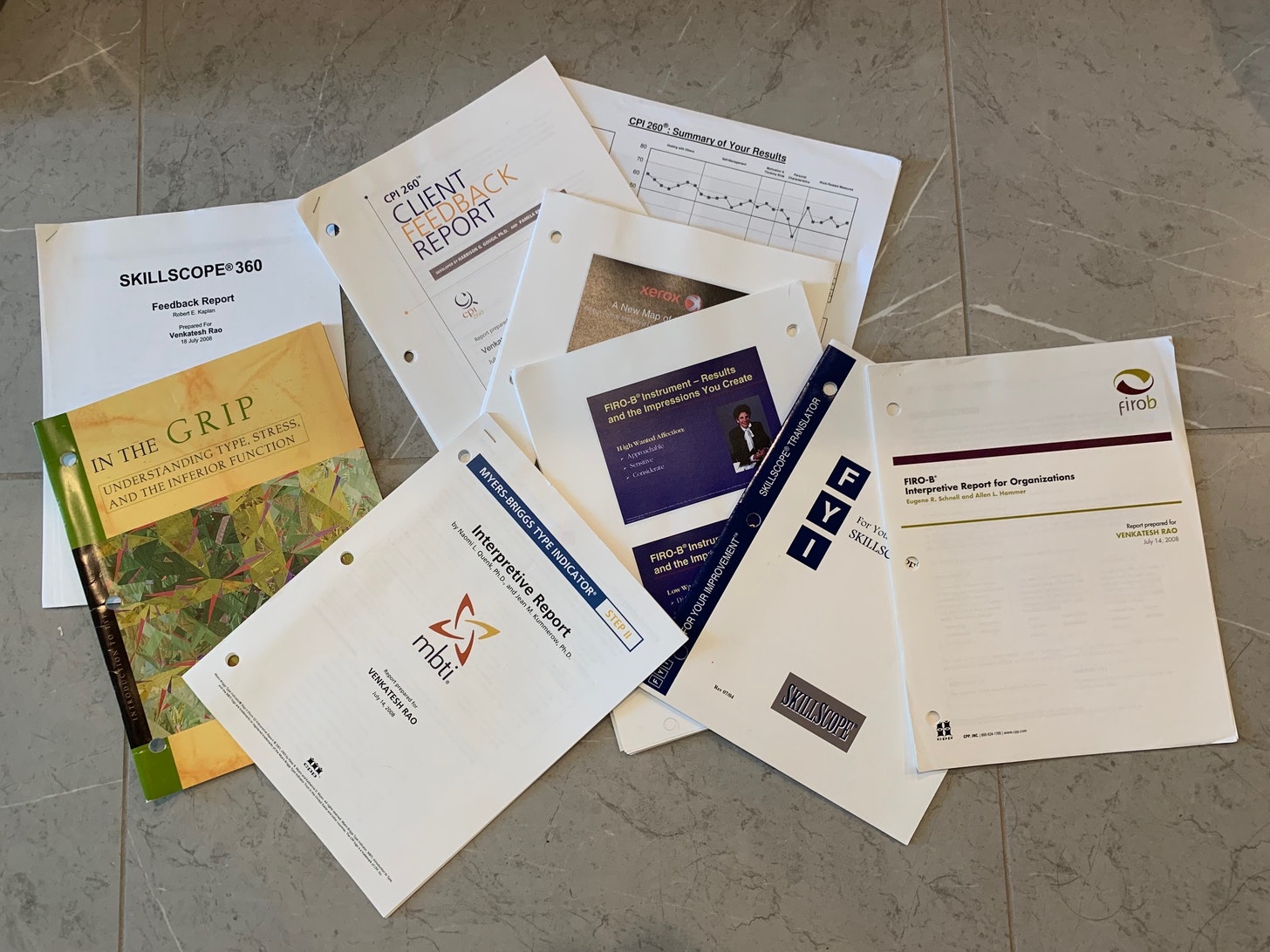

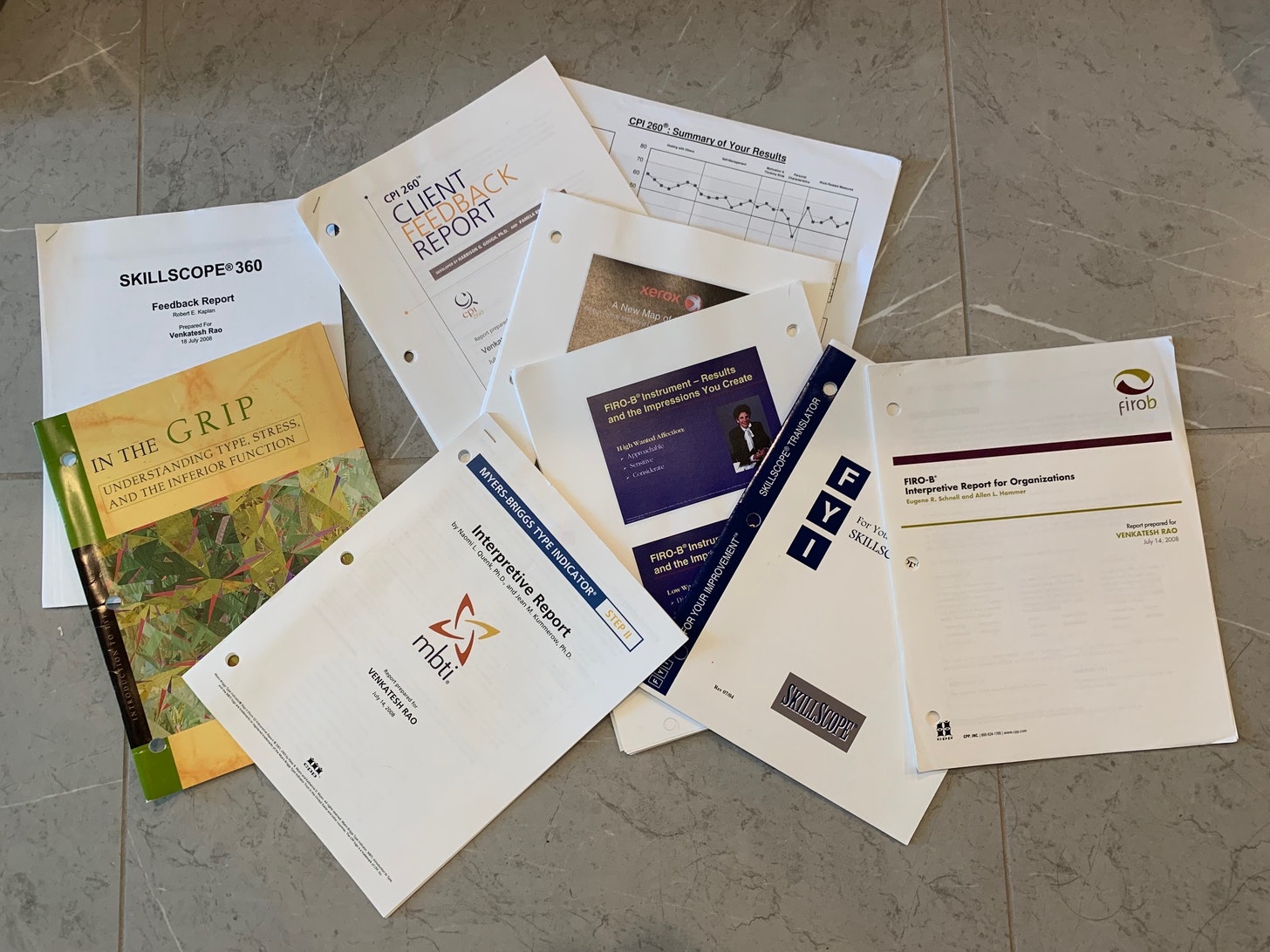

Back in 2008, when I was still confused enough about my own life priorities to imagine I might want to be on the executive-suite track myself, I was sent off by my employer, Xerox, to a “early high potential” leadership retreat at the Center for Creative Leadership, where I was subjected to a battery of psychological tests (Myers-Briggs, FIRO-B, CPI 260, Skillscope 360… see this pile of material I came home with).

It was a all a lot of fun, but felt like a bit of a LARP. Like I was pretending to be someone I was not — and doing it fairly well. Clearly, in some way I fit into this world, but not the way I was present in it during that program.

The capstone piece of the retreat was a couple of sessions with an executive coach. It was the first time I had done anything like it, and my expectations were low.

The exposure to executive coaching was particularly valuable because the coach assigned to me was pretty good at it, and it was a valuable session as a coaching session. I came away impressed by how well the coach had been able to get under my skin, and help me see some things about my behaviors. But I also came away with the impression that useful though it was, it somehow wasn’t even remotely helpful with the actual challenges I was facing at the time, in leading my project teams.

Perhaps that was just a matter of finding the right coach? Unfortunately, that’s not the case. I learned that my experience of coaching was in fact typical, from a book I read around that time: What Got You Here, Won’t Get You There, by Marshall Goldsmith, a pioneering executive coach, who in some ways invented the field (you can read my 2008 review here),

Goldsmith is known for pioneering the modern style of executive coaching, focused on behavioral rough edges. It begins with the assumption that anyone headed for the executive suite already has high competence and capability in their core leadership/managerial areas, but might require help addressing one or more seemingly innocuous blindspots and behavioral rough spots that end up being a huge liability.

Goldsmith’s model is the mainstay of 1:1 consulting models. As far as I can tell, all executive coaches practice some version of it, even if they’re not aware of it.

Unfortunately, the Goldsmith model has its limitations, and it became clear to me that coaching was not going to be the source of the kind of support I could actually use. Though I didn’t know it then, and didn’t call it that, what I needed — and never got — was sparring support. The few people around capable of serving in a sparring partner role with me were far too busy to spare more than the occasional hour, and usually available only when they wanted to talk to me, not when I wanted to talk to them.

Cut to three years later, in 2011, with my first couple of clients, it immediately became clear that what I was doing was in fact sparring — filling the gap I had myself perceived from the other side in 2008.

The idea that sparring is a distinct kind of 1:1 relational work has since been repeatedly validated by my experiences in the nine years since.

In fact, several of my wealthier clients have hired me for sparring while already working with both a coach and a therapist. These have been some of my best sparring relationships, because the client already recognizes that these are different roles, that call for different sorts of people to be cast in them. The sparring work does not accidentally slide into these adjacent kinds of work that I have neither the temperament, nor the taste for.

So that’s it for my introduction to sparring. In the coming weeks, I’ll cover several other topics: how to prepare for a sparring role, how to conduct yourself in a sparring session and in the follow through, assessing fit with a potential client, what kinds of potential clients to seek out or avoid, scoping engagements and setting expectations correctly, and how to find interesting sparring roles.

For now, I won’t be offering any in-person workshops outside of informal ones for people contributing to the Yak Collective, but if there’s enough interest, I might make an online course or something.

If you’re an executive looking for a sparring partner now, or might be looking in the future, drop me an email. One of my intentions in writing this series is to go beyond merely offering my own sparring services, to teaching the model and playing matchmaker to some extent, connecting executives with suitable sparring partners. We’ll see how that goes.