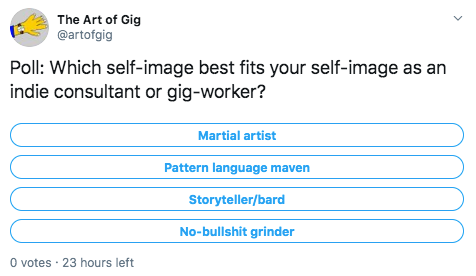

What should your self-image as a consultant be? Take a moment to pick an option on this Twitter poll before reading further.

There are others, but these are the most common self-images I see in people entering the indie consulting game. Each self-image induces a certain kind of structure to replace the structure you’re leaving behind.

Which is the right answer?

Paycheckier Than Thou

In the spirit of Halloween: this is a trick question, and all these answers are wrong.

There is a right answer, but first let me explain why your answer is wrong.

Your answer is wrong because each answer is basically an ersatz version of a non-indie consultant: a paycheck employee of an established, brand-name industrial-era consulting firm.

If that’s all indie consulting is — offering ersatz versions of services offered by consulting firms, for less money, and at smaller scale — then it is basically not worth doing. You may make money, but you likely won’t be fulfilled. You’ll always feel like a second-class citizen in a game pioneered by others, that they’re better at. A cheaper knock-off of a major brand.

There is a place in the consulting economy for the things non-indie consultants do, and for the brand-name consulting firms that employ them, but it’s not your role. It’s not your game.

So why do we gravitate to these self-images? Because uncritical imitation is easier than thinking about your own situation. That plus availability bias of real people to imitate. And the fact that they are familiar images to project to clients, making for easy (if not particularly effective) marketing and sales strategies.

The last few decades, from the 1970s to the early 2000s, were something of an aberration in the history of consulting, in that the craft became highly stylized, corporatized, and dominated by the non-independent kind of consultant. Consultants who were employees of larger consulting companies who aggregated talent capable of delivering against a particular codified consulting playbook.

Not only were typical consultants paycheck types, they were more paychecky than ordinary paycheck types, not less.

Despite a superficial branding of bad-ass mercenary guile, rank-and-file employee consultants were, by and large, the truest Organization Men, taking on less career risk in general than employees, not more. Employee-consulting in a large, established consulting firm is often a safer line of work than regular paycheck jobs, not riskier. If you get fired or laid off from a consulting firm job, you have more options open to you, in more industries, than a regular laid-off employee.

Cynicism about flavor-of-the-month business fads is for client employees. Non-indie consultants are usually true believers not only in whatever kool-aid they sell, but in the general idea of the industrial corporation as a model for organizing work. They are Extreme Organization Men (and Women).

As Upton Sinclair observed, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”

When your salary depends upon not understanding that you’re selling kool-aid, and that the cynicism on the other end is justified, you will work hard to not understand it.

The ordinary paycheck employee merely suffered through the latest flavor of the month, finding solace in watercooler grousing and Dilbert strips. The sociopath CEOs and the partner-level consultants selling them services merely practiced the age-old art of collaborative cronyist ruling from the top.

But the rank-and-file consultants actually delivering the goods? Everything from workshops in coding katas or design thinking to brand-narrative studies and heavy-lift spreadsheet models?

They believed. They had to. Their livelihoods depended on it.

What’s more, not only did they believe, they thought they were part of a more enlightened breed, tasked with raising the consciousness of cynical and apathetic regular employees with their wisdom. They thought their kool-aid was red pills.

Red pills for a particular subset of traditional employees.

Each of the four self-images in the poll represents an archetype that is symbiotic with a class of roles within traditional organizations. There are 4 such classes, giving us 4 True Believer paycheckier-than-thou non-indie consultant types.

True Believer Non-Indie Consultants

The industrial age corporation comprises four types of employees, each served by its non-indie consultant symbiote type.

-

Rank-and-file workers, served by martial artist trainer types

-

Staff management, served by pattern-language maven types

-

Executive leadership, served by storyteller/bard types

-

Line management, served by no-bullshit grinder types

Notably, very little of the actual playbook-deliverable work is done by senior-partner-level people in consulting firms who do take on non-employee type risks.

Let’s take these 4 in turn. Don’t forget: these are NON-indie consulting archetypes. They are paycheckier-than-thou Extreme Organization Men.

-

The martial artist trainer self-image was pioneered by productivity/efficiency focused consulting companies that supported training programs for skilled rank-and-file employees. Things like lean six-sigma, agile programming, and so forth. Programmers seeking philosophical inspiration often naturally turn to Asian martial arts because they feed a nerdy OCD approach to personal growth. They try to map martial arts concepts like shuhari, and kihon-kata-kumite to the problem of becoming more technically proficient. Consulting firms operating in this market gleefully co-opt this tendency in offerings like lean six-sigma with its “belt” system or “coding katas” used by agile programming trainers. Participation in such offerings feels like fandom to clients.

-

The pattern-language maven self-image was pioneered by design consulting firms (many drawing inspiration from the work of architectural thinkers like Christopher Alexander) that pandered to the vanities of aesthetes and wannabe autocrats seeking comprehensive “systems” for running little empires. Often, the target kind of client for such firms is people in staff roles without too much direct power over P&Ls. Such people are often in denial about their lack of real agency relative to line management, and eagerly latch on to any “system” that allows them to produce and consume process makework with combinatorial efficiency. A dead giveaway or tell is the production of stylized collateral information artifacts for their own sake. Participation in such offerings feels like cultural/art production to clients.

-

The storyteller/bard self-image was pioneered by marketing and advertising firms in the Good Old Days when powerful agencies of record led by Mad Men managed powerful brands and huge broadcast media budgets, farming out vast cascades of work in everything from graphic design to video production. The target was often vain senior executives in a mood to buy self-serving narratives which would offer them starring roles, and a delusion of more authorship over events than they actually had, while helping manage the optics of whatever universe-denting they were pretending to do. Often this kind of aspirational self-deception evolves in parallel with cynical stock price manipulation to maximize the value of their own compensation. Participation in such offerings feels like history-making or theatrical production of quasi-historical narrative — often both at once — to clients.

-

The no-bullshit grinder self-image is the most familiar of the four, and was pioneered by the Big 3 strategy consulting firms, who made the archetypal modern consultant a familiar figure: putting in 100 hour weeks, logging hundreds of thousands of frequent flyer miles, living out of hotels and weekend apartments. The calling card of this breed was the wonky spreadsheet, with which they “got real,” typically with the P & L line management types. Participation in such offerings often feels like martyred “real” work to clients.

What is common to all 4 breeds is that they are paycheck employees who:

-

Log billable hours but are protected from revenue volatility

-

Often work far harder than employees at the companies they serve

-

Are true believers in whatever playbook they’re running

-

Believe they’re enlightened cynics who see reality more clearly than clients

-

Believe more strongly in the roles they serve than the people occupying them

-

Aestheticize an area of work in ways that flatter the self-images of clients

This is why I call them paycheckier-than-thou. All four are terrible archetypes to model your indie consulting career on.

The Right Answer

I don’t want to be too hard on these archetypes. The playbooks they run offer a LOT of good raw material for indie consultants.

You can, and should, liberally steal from, and adapt, all 4 kinds of True Believer paycheckier-than-thou playbooks. You should mix-and-match gleefully. You should use their techniques the way guerrillas use the weapons they steal from the the larger conventional armies they go up against.

I do this liberally, stealing from all 4 sources all the time.

But what you shouldn’t do is adopt the associated self-images or associated overarching playbooks.

As an indie consultant, your situation is the opposite one from non-indie consultant types. Your livelihood depends on understanding what the non-independent consulting industry, in the form of larger firms, actually does. That’s the only way you’ll find a guerrilla niche for yourself in the landscape they’ve carved out.

Non-indie consultant self-images are liabilities for independent consulting. Your logged hours represent real money. Your attachment to every client rests entirely on the value of the last valuable thing you did for them. You cannot hide within the nebulous value proposition of a million-dollar “engagement” between two corporations. Your contributions (or lack thereof) cannot be safely hidden within the work of a large team.

For the non-indie consultant, there is no difference between running a playbook and making a difference. For the indie consultant, there is all the difference in the world.

Believing in any kind of kool-aid is an existential risk for you, even though it is a crucial enabler for some breed of non-indie consultant.

-

To the extent indie consulting is like martial arts training, it is closer to supporting someone as a wingman in a street fight than coaching them in a stylized dojo. You’re not Yoda, you’re Han Solo.

-

To the extent indie consulting is a pattern language, it is a jury-rigged library of cheap tricks collected from all over the place rather than a systematic aesthetic theory. You’re not Christopher Alexander, you’re a dumpster diver.

-

To the extent indie consulting is about storytelling, it is a shredded pile of narrative fragments, lending structure to moments of clarity in chaos rather than producing epics. You’re not Walter Isaacson, you’re a stand-up comic.

-

To the extent indie consulting is about no-bullshit grinding, it is about finding and doing the few hours of work that actually matter, buried in the 100-hour makework-week. You’re not Ray Donovan, but neither are you Tim Ferris, solving for 4 work hours. You’re a mystery-solving detective, putting in the hours actually needed to solve the case correctly. Sometimes that’s a 100-hour work week, sometimes it’s a 4 hour work week (and it’s never a straight line from interviews to spreadsheets to powerpoints).

If you don’t like these operating conditions, you shouldn’t be operating as an indie consultant. It is too real for you. You should be an employee in a larger firm (at least 10-15 people) where somebody else does the anxiety-inducing stuff for which there is no playbook.

But if you like the sound of this, when you put these dispositions together, you get only one answer: the indie consultant is a trickster, cobbling together bits and pieces in ongoing improvisation, sometimes sublime and inspired, sometimes just buying you enough time to dream up the next hack.

The indie consultant life is an endless Halloween, a string of trick-or-treat encounters with clients who generously play along, where the only thing keeping you philosophically honest is the fact that you have to live with yourself, with no playbooks or Senior Partners to blame for your failures.

And the goal of the trickery is to fool yourself and the client just long enough to accidentally do something right. And doing it despite instinctive attraction to stylized bullshit of one sort or the other operating on both sides of the table.

And if you’re lucky, maybe some of the tricks will be treats too.