Last time, in Your First Leap, we looked at the anatomy of the first leap into the gig economy. We looked at why people tend to fail at it by being underprepared in multiple ways. The lack of an obviously meaningful ceremonial starting point, like preparing a resume, pitch deck, or prototype, makes the problem worse.

So even though the risk, properly managed, is not significantly higher than a job search or entrepreneurial venture (lower actually, for people with ambiguous and/or low-demand skills), the outcomes are probably worse, because of these underpreparation factors.

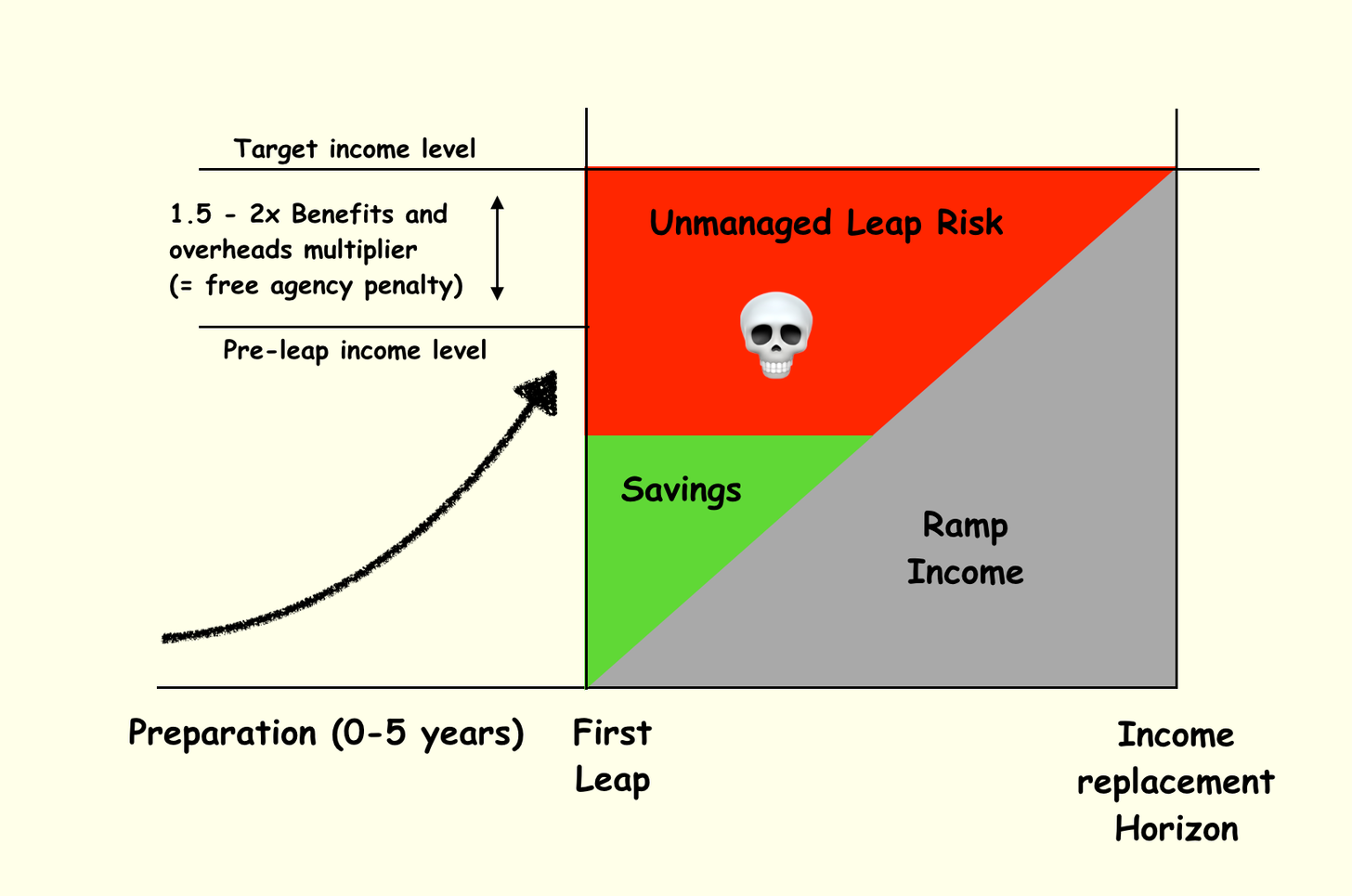

So how do you prepare? So let me give you a starting point that is both useful preparation and a good ceremonial starting point: computing your unmanaged leap risk, as illustrated in this diagram.

Our goal with this exercise is to first estimate your income replacement horizon (in months) and from that, your unmanaged leap risk (in dollars). Let’s make up acronyms for these, why not: IRH and ULR.

-

Income Replacement Horizon (IRH) is the transitional period you might have to endure to get back to your pre-leap lifestyle quality. There Will be a Dip. Your first leap is generally a planned economic recession in your personal life. The better you prepare, the shorter and shallower it will be.

-

Unmanaged Leap Risk (ULR) is the dollar value of the strategic cleverness you must bring to your leap to manage this unmanaged risk. I call it minimum viable cunning. MVC. Without MVC you won’t be able to close the strategy gap required for a successful first leap, and barring a big stroke of dumb luck, you’ll end up in a traumatic crash that might scare (and scar) you out of the gig economy for life.

In other words, the estimation model assumes you’ll be doing something meaningful to manage the unmanaged risk, not sitting on your ass, and that you will be successful. If you leave it unmanaged, or fail despite trying to manage it, the model breaks. We plan for success not because it is guaranteed, but because it is the only thing you can tractably plan for. Failure is much messier than success, and planning for it doesn’t actually help much (in fact it can hurt), so why bother.

Here’s an estimation example. It is meant to be illustrative, not definitive, and you have to get good at making up such rough models on your own.

-

Current monthly pre-tax salary: $5,000 ($60,000/year)

-

Adjust with 1.5 benefits/overheads multiplier (generic job, generic benefits, no special infrastructure): $7,500/month ($90,000/year)

-

Ramp length (divide by 10k, multiply by 4): 36 months/3 years <— This is IRH

-

Unchanged-lifestyle income needed till IRH (7500×36): $270,000

-

Average ramp income % assumption till IRH: 50%

-

Perfect nominal safety savings target (36 months * 7.5k * 50%): $135,000

-

Actual savings at first leap: $35,000

-

Unmanaged leap risk (135k-35k): $100k <— this is ULR

In other words you’re taking a risky leap worth $100,000 in strategic cleverness if you make it. Take a look at the image to get a visual sense of this model.

The basic idea behind this computation is derived from job searching, but drastically modified. In job searching a common heuristic is that you can expect to look for a job for 1 month for every $10,000 in income. So a $60,000 job means 6 months of looking (and therefore having up to 6 months worth of savings for the most conservative preparation).

But the equivalent rule of thumb for a gig economy launch is that you can expect 4 months of ramping for every $10,000 in paycheck income (benefits-and-overheads-adjusted) you want to replace with gig income. So that same $60,000 income (worth $90,000 including benefits-and-overheads value) will take 36 months to replace, rather than 6.

This benefits-and-overheads value of a paycheck job is something like a free agency penalty because you have to make up for it on your own, often paying a higher direct and/or hidden cost.

If you were in a basic generic skills job, the multiplier of about 1.5 accounts for having to provide for yourself the basic amenities that jobs generally provide. Like health insurance (in the US), a retirement plan with matching, a computer loaded up with generalized and specialized productivity software, support from staff functions like accounting and administration, and most importantly, invisible perks like easily getting a lease or mortgage (via employers underwriting the risk of landlords renting to you, or banks lending to you, by guaranteeing your income).

How much in savings do you need before you take your first leap? Assuming a linear gig income ramp as shown in the diagram (optimistic; it’s more likely to be an S-curve where you draw down savings faster in the beginning), you can assume that about half your income needs in the interim will be met by live earnings. Revise this upwards or downwards depending on how in-demand your skills/services are.

So a 36-month replacement horizon for a 60k job with a 1.5x multiplier amounts to about $270,000 as an income planning target, assuming no downward adjustment in lifestyle. If you expect to meet half of this, or $135,000, with ramping income, you’ll need $135,000 to make the leap with complete safety and no significant lifestyle risks.

But obviously, trying to hit 135k in liquid savings on a 60k salary is ridiculously unrealistic for most people. At a very aggressive savings rate of say 20%, above and beyond retirement savings, it would still take you 10 years to prepare to leap. You’d effectively never do it if you’re that risk-averse.

A good way to think of this is in terms of a time advantage. You’re hoping to make up for this 10-year-long, dumb, no-risk preparation time with sheer strategic cleverness. You’re trying to leap 10 years into your own future, financially, by getting inside your own OODA loop somehow. You’re trying to disrupt yourself.

So you’ll leap with much less than the “safe” amount. You’ll take a risk and bet on your own resourcefulness. In the example, I’ve assumed 35k in savings, leaving 100k unaccounted for.

This difference is a measure of your ULR.

If ULR is zero, you’re not taking enough risk, or equivalently, you’re waiting too long to leap. But if you’re not doing some cunning strategery to manage this risk with levers besides more saving or drawing down other assets (second mortgage, borrowing against retirement account), you’re not being strategic enough.

In other words, you need to take on pretty high unmanaged leap risk, equivalent to a year or two of your current income, and then manage it using things other than money.

There are 4 main cheats for managing the risk: favorable exit conditions, a parental factor, a spousal factor, and a transient lifestyle cost-down (a permanent cost-down is not a strategic move; it is a values shift towards frugality or a cheaper “lifestyle design” in Bali).

Without cheats to manage it, the unmanaged risk part translates to an expectation of pain. Like homelessness pain. Or hunger pain. Or credit-card-debt pain. Or compounding-health-issues pain. Or tanking-mental-health pain. Or being-a-burden-on-friends-and-family pain. Or marriage-breaking-up pain. Or children-taken-away-by-social-services pain. Or doing-without-vacations pain. Or cutting-back-on-lattes pain.

You’re not a masochist. You don’t want to experience any of this pain. And if you plan right, you may not have to. Chances are you won’t get out of Ramping Jail free, but you can minimize the pain.

Your lifestyle pain tolerance may be high for merely staying alive, but to make a gig economy leap work, you can’t be in extreme, chronic lifestyle pain. You need a relatively clear head and a couple of latte treats a week.

And there are no dignity prizes for handling homelessness or untreated diabetes well.

So don’t be a hero.

Cheat.

Figure out a way to cover the unmanaged leap risk, or ULR, with things other than money. Conjure up the minimum viable cunning somehow.

Next time, we’ll look at cunning plans for doing this.