Last week, I introduced the idea of executive sparring as a practice distinct from coaching. Continuing the series, this week I want to talk about the most crucial aspect of being a sparring partner — developing and embodying a deep, appreciative world view complementary to that of leaders of organizations, which makes you a useful foil to them in their work.

For better or worse, getting into the sparring partner business means coming to terms with a growing perception of a “guru factor” around what you do — even if you are younger and less experienced than your clients. This is a fraught business. It creates serious reputational jeopardy. There is a fine line between “guru” and “laughing stock” (or to use a more appropriate modern term, lolcow).

The jeopardy turns into double jeopardy if you happen to be Indian. And into triple jeopardy if your middle name happens to literally be Guru.

I’m not complaining. Just noting obvious facts.

So a good way to start figuring out the core of the appreciative worldview that can potentially form the core of your sparring practice is to own the guru-jeopardy and ask — what am I a guru of?

Take a stab at answering that question before we unpack the concept. As a hint: contemporary Western usages, such as unix guru, design guru, and of course, management guru, are actually closer to what I think is the correct understanding of gurudom than the literal translation of teacher.

The core of gurudom is not a teacher-student relationship, but a seeker-world relationship.

Nerding out over the innards of Unix, and developing an appreciative worldview through the lens of that nerding out, is closer to the true spirit of gurudom than being good at teaching computing skills. Gurudom is nerddom plus a certain guru factor.

Being a computer science teacher makes you a good person to learn (say) sorting algorithms or good Python style from. But being a Unix guru makes you fun to spar with about the future of computing, and an interesting companion for explorations of that future. People can go as deep as they like with you, knowing that you can keep up, even if you don’t agree with them.

Sparring and Appreciative Knowledge

Appreciative world views, which are at the heart of guru factors, emerge via accumulation of appreciative knowledge, a term due to urbanist John Friedman, who defines it in his book Planning in the Public Domain as follows:

The social validation of knowledge through mastery of the world puts the stress on manipulative knowledge. But knowledge can also serve another purpose, which is the construction of satisfying images of the world. Such knowledge, which is pursued primarily for the world view that it opens up, may be called appreciative knowledge. Contemplation and creation of symbolic forms continue to be pursued as ways of knowing about the world, but because they are not immediately useful, they are not validated socially, and are treated as merely private concerns or entertainment.

Friedman uses the term manipulative knowledge in opposition to appreciative, but he doesn’t mean manipulative in a Machiavellian sense. He simply means knowledge of how to actually do things to drive change in the world, accumulated by actually trying to do those things.

I prefer the term instrumental knowledge for this. I previously wrote about appreciative versus manipulative (or instrumental) knowledge here, if you want to go deeper, but in this post I want to apply the distinction to consulting work, especially sparring.

Here is the big idea to keep in mind:

About 90% of your effectiveness as a sparring partner derives from the depth of your appreciative world view, developed and expressed through critical reading, writing, podcasts, and talks. Only about 10% depends on your in-session sparring skills.

In this, sparring skill is similar to negotiation skill. In negotiations, 90% of success depends on the preparation you do before you sit down at the negotiation table. Only about 10% depends on your negotiation skill.

Gurus versus Pundits

These activities at the core of strengthening appreciative capacity — reading, writing, podcasts, and talks — are not primarily marketing activities, though they do serve a marketing function as a side-effect. They are integral to developing your capacity for sparring, but pursuing them for the sake of getting better at sparring doesn’t work.

I think of these activities as nerdy reflection, something very few people have much time for. It’s a time-wasting, bunny-trail-exploring nerding-out over the significance of things you’re seeing in your life.

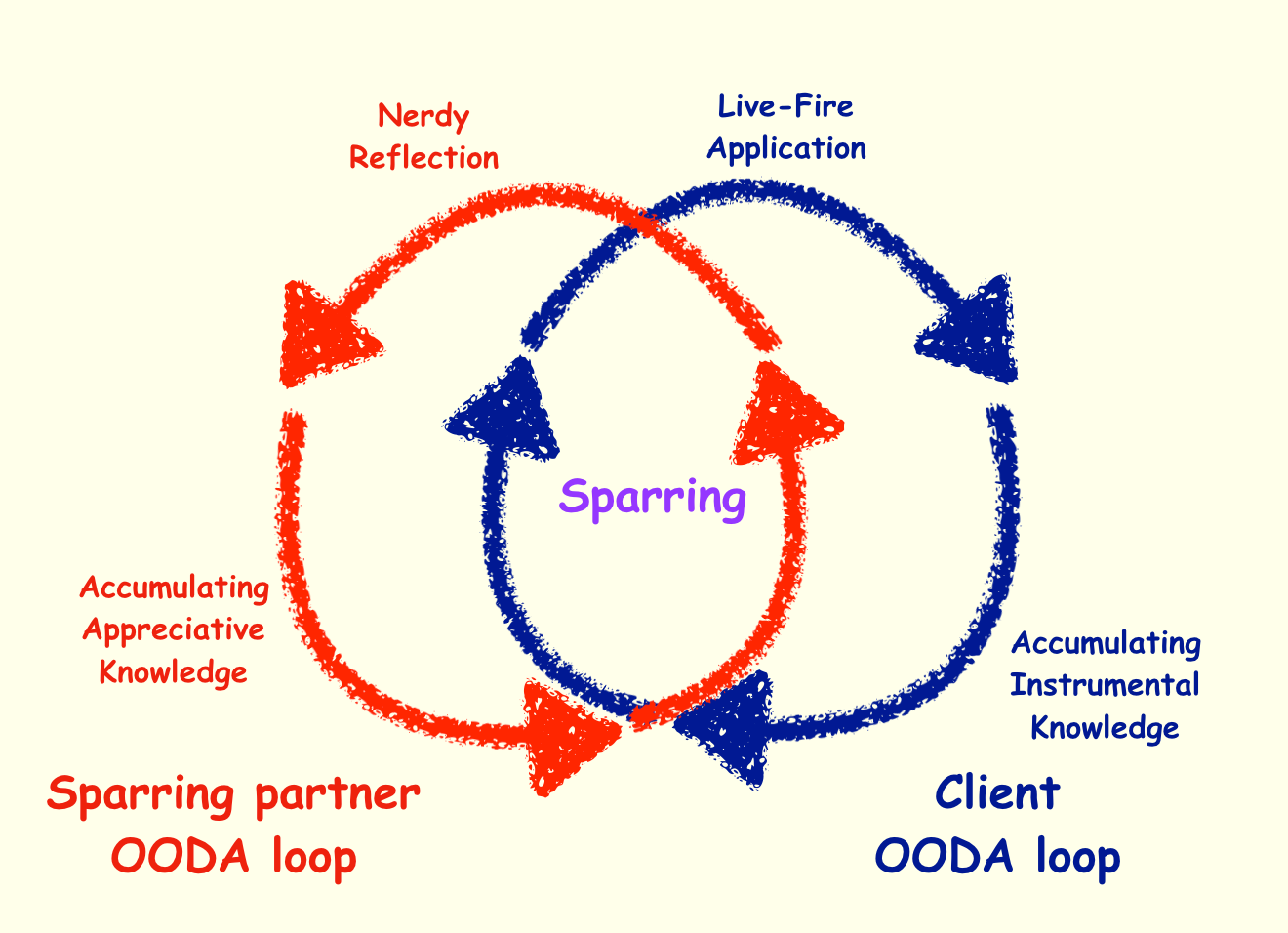

So how do you develop appreciative capacity? The linked OODA-loops diagram above should convey the gist. You and the client are each driving complementary OODA loops that intersect in the practice of sparring. You are inside each other’s OODA loops in a way that mutually reinforces both your learning processes. Yours is an appreciative learning process, theirs is an instrumental learning process.

This means you cannot become a “guru” at something by deciding to study all the classics relevant to your interests. That turns you into an erudite scholar, an entirely different thing.

Why?

For much the same reason you cannot become a unix guru by reading scholarly papers and books about operating systems. You have to be at the keyboard, messing around with shell scripts, hacking away.

More generally, you cannot develop appreciative capacities in instrumental ways, anymore than you can develop instrumental capacities in appreciative way.

Here is another way to think about it: you cannot learn how to swim by reading a hydrodynamics textbook on dry land. But equally, you cannot figure out the molecular structure and chemical properties of water simply by swimming around in it.

This is easy to get when we’re talking about swimming versus chemistry, but gets a little tricky and very meta when we are talking about instrumental versus appreciative approaches to book-learning itself.

The thing is, instrumental means develop prowess at instrumental capabilities rather than appreciative capacities, even when the object of the learning activity is appreciative knowledge. You do have to develop your instrumental scholarship capacities to some degree, but they can’t be the primary focus.

That is not to say becoming an erudite scholar with a command over the canonical texts of a tradition is not a worthwhile thing. Go for it if that’s your thing. It just doesn’t develop sparring capacity or a guru factor.

If you are a completist about Sanskrit words for these things, the word for erudite scholarship has been imported into English as well: pundit (in India it is usually spelled Pandit, and is a common last name, as is Acharya, which is roughly synonymous). The differences are worth noting:

-

Pundits engage in scholarly debate with each other within an institutional tradition, and are governed by internal conventions and hierarchies. Gurus spar with all interesting comers, be they beggars or princes, and in any context.

-

Pundits can become institutional stewards of traditions, but rarely create new traditions. Gurus often create new traditions, but usually end up on the margins of even traditions they helped create.

-

Pundits often gain a great deal of worldly fame, wealth, and power, and this is viewed as just reward for their institution-building work. Gurus on the other hand, rarely do, and if they do, are viewed as having sullied their reputations.

-

Pundits represent and embody institutional epistemic authority, and take offense at challenges to that authority. Gurus have no such formal locus standi in relation to the traditions they may draw upon, and are rarely offended by challenges to their authority because they claim none to begin with.

-

Pundits often participate in visible and ceremonial and ritual forms of knowledge performance as the core of their work (traditionally, conducting temple services or sacrificial rites). Gurus typically do not. In consulting, this maps to doing talks or workshops around fully formed theories, versus informal “theorizing” discourses.

-

Pundits often present in highly ceremonial and authoritative ways, with a strong and consciously crafted halo, but often accompanied by ritual protestations of humility. Gurus stereotypically present in self-effacing ways, often being mistaken for beggars, but often present in poorly socialized ways, as irritable curmudgeons, or unpredictable trolls for example.

-

Pundits typically enjoy teaching, usually do it very well, and seek out opportunities to do more of it. Gurus typically don’t enjoy teaching, usually do it poorly, and seek excuses to avoid doing it.

The tension between pundits and gurus is so commonplace, it is practically a trope in Indian history. Similar archetype pairs exist in other traditions. In the Christian tradition, the distinction between regular and secular clergy is somewhat similar, as is the one between research and teaching faculties in universities.

A loosely similar modern one is the Straussian distinction between “great thinkers” and “scholars,” though that one is fraught with additional political-philosophical baggage, and conservative norms of reverence of ancient traditions that makes it not quite analogous.

Why does all this matter?

It matters because appreciative knowledge is not punditry.

Punditry is the result of an instrumental approach to appreciative knowledge. Gurudom by contrast, is the result of an appreciative approach to instrumental knowledge.

(for completeness of the 2×2, an appreciative approach to appreciative knowledge makes you a critic, and an instrumental approach to instrumental knowledge makes you a vocational learner).

In the world of consulting, gurus favor freeform sparring, backroom influence, and proximity to consequential decision-making. Pundits favor developing and delivering workshops and talks, building scaled institutions, and crafting powerful public images. Pundits develop personal brands (not always strong ones). Gurus develop reputations (not always flattering ones).

Both usually do at least a little of the other kind of activity out of necessity, but basically you have to choose, and choose fairly early, which path you want to go down. It’s like figuring out if you’re left-handed or right-handed. I’ve done my share of workshops, public speaking, and teaching. But none of that stuff comes naturally to me, I’m not very good at it, and I don’t enjoy it much. For better or worse, I’ve wandered down the guru path rather than the pundit path.

Peripheral Learning

What do I mean by “appreciative approach to instrumental knowledge”?

A good way to think of it is: Gurudom is weakly codified appreciative knowledge of the sort that develops on the peripheries of instrumental practice. The kind of knowledge that develops when you let attention wander towards the margins of instrumental activity, to metacognitive musings around it. You do have to play, but if playing well becomes the whole point, you’re better suited to playing excellence than coaching excellence.

Here we run into a problem though. Letting your attention wander to the margins of instrumental activity is dangerous. If you do it in mission-critical situations, you can become distracted and make costly errors.

This is one reason the best sports coaches often turn to coaching after mediocre career as players. A weakness for metacognitive distraction that diminishes performance on the field turns into a strength in coaching.

In live-fire situations, letting your mind wander to metacognitive concerns is often a sign of an even deeper weakness. It is a sort of displacement activity triggered by fear or anxiety, rather than actual philosophical curiosity about meta-concerns. This sort of person does not turn into a good coach, because they typically exit the live game with too much insecurity to be effective foils to better players.

There is, however, one activity which allows you to safely let a significant portion of your attention wander to the margins of instrumental activity.

This is of course sparring.

Linked Learning Loops

We are now in a position to appreciate the linked-loops diagram at the top of the page, representing the sparring process.

Sparring is a safe-fail activity immediately adjacent to live-fire activity. It benefits from a little bit of peripheral attention-wandering. It benefits from the kind of experimental trial-and-error attitude, accompanied by mindful critical attention, that is fueled by things you notice out of the corner of your eye.

So appreciative knowledge developed through the work of peripheral attention during sparring is what compounds gurudom, and makes you better able to spar.

This might sound like “the best way to get good at sparring is to do more sparring,” but that’s not quite it. While there is a component of mindful deliberate practice, it is only necessary, not sufficient, and it’s not unique to the sparring partner. The principal too, has to be mindful in that exact same way during sparring sessions, letting attention go to peripheral vision to a far greater extent than they would in the ring during an actual bout.

What makes the sparring partner role different is that you take the fruits of marginal attention around sparring and convert them into nerdy explorations which then turn into fodder for your own private pursuit of things that interest you (via writing, reading, and such), creating a growing store of appreciative knowledge. It is a virtuous cycle that powers growing guru-dom. This is the red loop in the diagram.

The yang to that yin is the loop experienced by the client you are sparring with. In the best case, the same sparring experience is cashed out differently. For the client, the fruits of marginal attention around sparring is converted into superior live-fire application, which leads to a growing store of instrumental knowledge. This is the blue loop in the diagram.

These two loops — both of which are metacognitive OODA loops with the sparring serving as an “Orientation” activity for both parties — are at the heart of sparring.

Where this beautiful symmetry breaks down is in the relative value of the two loops. The client’s loop passes through the real world. The sparring partner’s loop passes through the adjacent possible of the real world. The former, by virtue of having more skin in the game, is worth much more money. This is why the client typically pays the sparring partner rather than the other way around.

If the sparring sessions go well, the client will be forged into a better live-fire decision-maker and leader, while you will inevitably develop tendencies of a guru-like nature, whether or not you want them.

Recognizing Gurudom

The process I’ve described above should make it clear that you cannot actually choose to become a guru. Equally if you’re doing certain things well enough to be paid to continue doing them, you cannot avoid becoming a guru either.

This means gurudom is a tendency in your life that you recognize and come to terms with at some point, based on how people are choosing to relate to you. Including both how they are laughing or sneering at you, and how they are praising and appreciating you.

Again, think unix guru, design guru, or management guru. Not guy with long beard running a commune with sex slaves in the basement and Rolls Royces in the garage.

Some willingly lean into gurudom, some have it thrust at them (and some, like me, have it hang over their entire lives thanks to nominative determinism — I’ve been the butt of “guru” jokes since age 10, thanks to my middle name).

Gurudom is not primarily about a teacher-student relationship. A guru, or equivalent concept in other cultures, is rarely primarily a teacher, though teaching activity usually occurs on the margins of gurudom. The concept of a guru combines four elements that all play a role in sparring:

-

Reluctant teaching that is closer to preceptorship

-

Individual striving for esoteric appreciative knowledge

-

The capacity to keep up with others on their journeys

-

A degree of genuine (and costly) indifference to worldly rewards

Of the four, the teaching element in a conventional sense is the least important. It is the one that can be most easily delegated to others, and often is, at the first opportunity.

In the traditional Indian education model, known as the guru-shishya parampara (literally, “teacher-student tradition”), only the very earliest stages — the first few years — look like conventional teaching, focused on drills, repetition, and homework. And these are often handled by senior students of the guru, much like how graduate students do much of the actual teaching in American universities.

Teaching responsibilities can in fact seriously interfere with the actual responsibilities of gurudom, which are closer to “research” in the academic sense, but not quite the same.

As a result, gurudom finds its best expression via two core activities: sparring with peers in the same intellectual weight class, and through the ongoing development of an appreciative world-view. This latter activity can be understood as being a preceptor, which is closely adjacent to, but not the same as, being a teacher.

The natural fit with sparring and preceptorship is why faculty in American research universities are generally terrible teachers, prefer PhD students to undergraduates, and prefer to treat those PhD students as much as peers as possible, often handling actual advising responsibilities with great reluctance.

As with universities, which evolved in the West from the priesthood, with its vows of poverty and chastity, the guru tradition too has an uncomfortable relationship with worldly wealth. In India, gurus were traditionally expected to live in simplicity and relative poverty in humble ashrams in the forest, outside the civilizational core. They were expected to spar with kings, train princes, groom their own replacements, and produce pundits for the institutions that needed them.

The word is usually translated as hermitage in English, but modern day ashrams run by literal gurus are often relatively luxurious retreat destinations, suitable for entertaining kings and presidents, with great comfort lurking beneath a facade of theatrical simplicity.

Management gurus of course, usually skip the simplicity signaling and go straight for the 5-star leadership retreat experience in lieu of real ashrams.

The spirit of the ashram tradition though, is today best represented by the research laboratory, rather than a luxurious leadership retreat campus.

Emissary of the Adjacent Possible

Past the basic drilling stages, in the traditional Indian model, the student progresses to something that resembles more of a sparring process, focused on debates and disputations around classic texts.

These start out as rehearsals of traditional arguments around age-old questions, heavy with appeals to authority, and progress to increasingly free-form open debates on the “live” questions of the day. By the time the student gets to advanced stages, striving to best the master, in “the student becomes the master” mode, is the expected mode of engagement.

Here a fork in the road appears. The princes of course, go back to their kingdoms, assassinate their fathers, and ascend to their thrones. As adults, they may return to spar with their gurus.

As for the rest, some head towards punditry — stewards of the tradition within institutions embedded in secular life within the civilizational core. Others stay on the margins, and head towards gurudom in their own right — setting up the equivalent of experimental laboratories for their own nerdy reflections as best as they can.

This developmental path is not restricted to intellectual traditions. You can see a similar path in Indian music education, which begins, as in the West, with young students practicing scales and set compositions in ragas, and moves on to learning to render compositions in particular styles, peculiar to specific traditions. But at this point it diverges from the Western music tradition, and heads towards the free-form structured improvisation that is raga performance. These performances often involve a strong element of sparring with accompanying musicians (similar to call-and-response jamming as in jazz) known as jugalbandi.

Some version of this can be found all over the world of course. In Japanese martial arts for instance, we find the idea of kihon (drills), kata (set forms), and kumite (sparring). In the medieval European tradition of gallantry, young noble-born boys were sent off to serve as squires to peer knights, where they learned jousting, horsemanship, and other knightly skills.

Historically, this kind of education has always been something of a luxury, since it cannot be delivered at scale. Around the world, it was largely only available to princes being groomed for imperial leadership roles, or commoner students showing some promise as future pundits and gurus. There is a reason it is generally restricted to business executives today — paying someone in your intellectual weight class to spar 1:1 with you is not cheap.

For those providing this kind of education, the core activity — call it research, call it nerdy reflection, call it saddling senior students with the real teaching duties and sneaking off down bunny trails — became a way of life. Those who adopted this way of life, whether they were called gurus or something else, primarily engaged with the civilizational core by sparring with its leaders — and those being groomed for leadership — at the margins.

That is the essence of the guru factor — your stake in the margins of civilization, as an embodiment and emissary of the adjacent possible, bringing appreciative knowledge to life in the real world.

That’s a rather nebulous thing to try and be. But the core is simple enough — spar, nerd-out, write/speak about, spar some more. Pick people who you can keep up with, and who can keep up with you, as your sparring counter parties, regardless of what they can pay you. Recognize the adjacent activity of punditry and consciously choose one or the other.

The rest is just a matter of doing this steadily, for years, making money as best you can along the way.

Next time, we’ll talk about the actual content of accumulating appreciative knowledge, the content of your guru-factor, but to set it up, consider the opening question: what are you a guru of?

“Nothing!” is a perfectly fine answer.

Gurudom is something that creeps up on you after years of messing around, nerding out over things that interest you, and sparring with people. If you do have an answer, it is probably something that happened when you weren’t really looking.

For me, it happened to be organizational sociopathy and office politics.

The good news is, if you’re a guru of something, it isn’t a box that contains and confines you. That’s a price you pay for the rewards of punditry.

To be a guru of something is to look at the world through that thing rather than being put in a box defined by that thing. There are no restrictions on what you’re allowed to look at. The thing you’re a guru of is merely the appreciative perspective on the world people associate with you.

In other words, if people want to learn about X, they go looking for a pundit of X. If they want to see some aspect of the world through X, they go looking for a guru of X.

You can now ask useful follow up questions.

-

Is your relationship to appreciative knowledge closer to punditry or gurudom?

-

Is that what you actually want?

-

If you somehow ended up on the wrong side of that divide relative to your natural inclinations, how do you cross over?

-

How should you relate to those on the other side? As complements? Evil twins? Deadly rivals?

All useful questions, which we’ll get to in the next part.