Money is an unseemly topic to discuss in the paycheck world. There is a fairly strong global social taboo around openly discussing salaries.

Less obviously, it is an unseemly topic in the indie consulting world as well. We just don’t notice as much because, conveniently enough, it also happens to be harder in practice to do the math to get to taboo-worthy paycheck-equivalent numbers to compare. But that doesn’t mean we are any more willing to discuss income openly.

But more interesting than the mere existence of comparable taboos in the two worlds is the fact that they exist for different reasons.

In the paycheck world, the taboo exists so it is easier to fake your position in the keeping-up-with-the-Joneses rat race. But that doesn’t explain the taboo in the indie world, since we very theatrically quit the rat race as our opening gambit, often with some holier-than-thou posturing and manifesto-writing accompanying our exits (which is fine; a bit of positive self-talk to work up the courage to quit is perfectly acceptable).

So what’s the deal with our version of the taboo? And should you break it?

The Salary Discussion Taboo

In the above-the-API paycheck world, it is obviously beneficial to employers if employees don’t discuss salaries openly, and though in the US you cannot be legally prohibited from doing so, many employers strongly encourage the norm. Many even institute it as a policy, though it cannot be legally enforced.

The thing though, is that employees don’t really want to discuss their salaries openly any more than employers want them to, whatever the cost in terms of ceded salary negotiation leverage.

Periodically there are calls by well-intentioned people to “normalize” open discussion of salaries, but it never works and never will.

Why?

In the modern world, income, identity, and social status in the middle class are too tightly coupled for talking openly about salaries to be comfortable. Revealing how much you make has social consequences. Gaining salary negotiation leverage against employers is a secondary consideration. Maintaining a social status quo relative to neighbors and work peers is primary. Your neighbor (or coworker in the next cubicle or Zoom window) with a very similar home and car may be making twice what you make, and have half as much debt, but you wouldn’t know it — and it is in both your social interests to pretend the differences are smaller than they might actually be.

The salary taboo is a peculiarly middle-class thing, and there’s a history to it.

Through most of the twentieth century, as the middle class grew and absorbed chunks of the working and wealthy classes, the taboo grew in strength. Socially, the middle class is much more egalitarian than either the wealthy or the working classes. Markers of differences in wealth and income are subtle and understated. The differences are not denied, but their social consequences are consciously minimized. Shared social realities — such as schools and community centers — present a facade of near-absolute equality. Even in the US, where homogenizing norms like school uniforms are uncommon, flaunting your parents’ wealth too openly, or failing to adequately mask their lack of it, marks you for social consequences.

After 1980, as the middle class began to both shrink and socially fragment under economic stress, the taboo weakened, but only slightly. Social life in the middle class depends too much on the pretense of relatively equal, or at least non-traumatically-comparable lifestyles, for the taboo to dissipate. A twinge of envy when you look over to your neighbor’s driveway is not just acceptable, but desirable. But you don’t want such casual awareness of your social milieu to turn into suicidal despair at the unfairness of the universe.

All this tempers the impulse to share salary information, and the impulse is not class-native to begin with. So where did it come from in the first place?

The thing is, the very idea of trading salary information for shared negotiation leverage is fundamentally a working-class solidarity tactic.

In the working class (what used to be called blue collar or service labor, and I call under-the-API work in its modern form) openness about pay harmonizes well with things like unions and fungible labor.

In the traditional working class, people were much more interchangeable. They were valued by role, and by a relatively straightforward correlation between experience (“seniority”) and a worth-in-role perception that was relatively independent of skill (unlike modern white-collar work or pre-modern craft work).

It’s not that the working classes are less socially competitive — it’s that they are too interchangeable at work for work identities to form much of a basis for individually differentiated social competition.

As a result, working-class Joneses around the world compete socially in other ways. In the US, historically, things like Christmas decorations, bowling scores, baking skills, chili recipes, drinking stamina, and dancing abilities have mattered more than income. Neighborhood “Big Man” types dominate local social hierarchies much more than in the middle class.

Among the wealthy, of course, the discussion is moot. Net worth and political power are far more important than salaries (and indeed, among the truly wealthy, living off investment income is the norm, and working for money at all marks you as not-quite-top-shelf).

Now consider the corresponding picture in the indie economy.

Indie Income Illegibility

To be clear, I’m talking above-the-API new-white-collar indies, not Uber drivers. Below the API, if you do particularly well or poorly, there are incentives to brag or complain, since it reflects on algorithmic casino dynamics more than your personal character. Above the API, things are more complex.

To begin with, talking about money at all is basically harder for indies, for several practical reasons:

-

More dimensions: It takes more numbers to capture even a basic picture of an indie consultant’s personal finances. At the very least, you need their effective hourly rate, number of hours actually being billed at that rate, and routine operating costs, all of which are uncertain and radically variable. Most indies don’t even have a good handle on their numbers. Sharing them openly is moot.

-

More complex costs: Unlike paycheck employees, indies may have wildly varying non-routine costs due to things like subcontracting, paying for their own tools, and self-funded spec work which may involve upfront costs like travel and capital equipment, or just drawing down savings and turning down paid work (an opportunity cost) to invest in spec-work with higher potential.

-

Lower lifestyle correlation: You cannot easily guess income from visible markers like type of work (descriptors like “strategy,” “coaching,” and “design” reveal almost nothing), type of car a person drives, or what neighborhood they live in.

-

Lifestyle design: Indies have the freedom to do a lot more strategic lifestyle design, and many make heavy use of that freedom, which makes apples-to-apples comparisons with the Joneses harder. In a sense, it’s closer to comparisons across countries than across fences. Every indie is like a country unto themselves, even if they don’t move to Thailand.

-

Wealth-income blurring: Despite typically middle-class financial profiles, the financial and risk-management style in the indie world resembles that of the wealthy class, with a weird mix of work-for-hire income and cash flows that look like investment income. Once you are somewhat established, there are usually capital-like assets in the mix (such as book royalties, affiliate income, or pre-recorded courses) that have no clear social significance.

-

Tax-optimizing behaviors: Even when indies pay themselves a regular paycheck (such as you’re required to do with an S-corp in the US for instance), the numbers are designed to minimize taxes rather than maximize a vanity number. Other tax-driven behaviors include choices of where to live, renting an office vs. maintaining a home office, how you handle insurance, and so on.

Given all this complexity, indie income is highly illegible.

Personally, I really only get one meaningful snapshot of my income per year, when I do my taxes. And even that is shaky since I sometimes defer revenue or expenses, and at other times, take money in one year for work that will be actually be done in the next year. Once every few years, I sit down and do some analysis, but it’s a pain to actually keep track in any detail.

So the headline — but not the bottomline — is that indie income is fundamentally more illegible.

Now, it wouldn’t actually be that hard to set up systems to do the math and come up with a fairly accurate “paycheck equivalent” number. If you do your books properly, you’d just need to spend more time (or pay your book-keeper more) to generate an additional report in QuickBooks. But doing the math wouldn’t be hard. In the simplest case, it would look something like this.

-

Trailing 12-month revenue: $100,000 (accrual basis)

-

Trailing 12-month costs (including subcontracts etc): $20,000

-

Moving average monthly salary-equivalent: $6667

In more complex cases, you’d have to put some thought into building a good equivalency calculation model (did you account for typical employer-matching contributions to retirement accounts and health insurance? How about any creative (but hopefully legal) expensing you might be doing, to move some costs from your personal to business budget?

But here’s a more basic question.

Why do you want to know this number, let alone share it openly?

What would you do with it if you set up some scripts to compute it every month? How does knowing the number help when you’re facing a cash crunch right now due to late invoices or a dry spell? How does it help you set an hourly rate?

And there are good reasons to not want to know.

Because you see, like our friends in the paycheck world, we don’t want to talk about it either. But for different reasons.

The Indie Income Taboo

The indie consultant class is, socially, part of the middle class. We tend to live roughly middle-class lifestyles in middle-class neighborhoods. Our friends in the paycheck world tend to be middle-class too.

So one obvious reason we share a paycheck-discussion taboo is that we still belong to the class that has such a taboo, even though our economic lives have changed. Sheer force of habit, and ongoing social reinforcement are powerful.

But that’s only a small part of the reason.

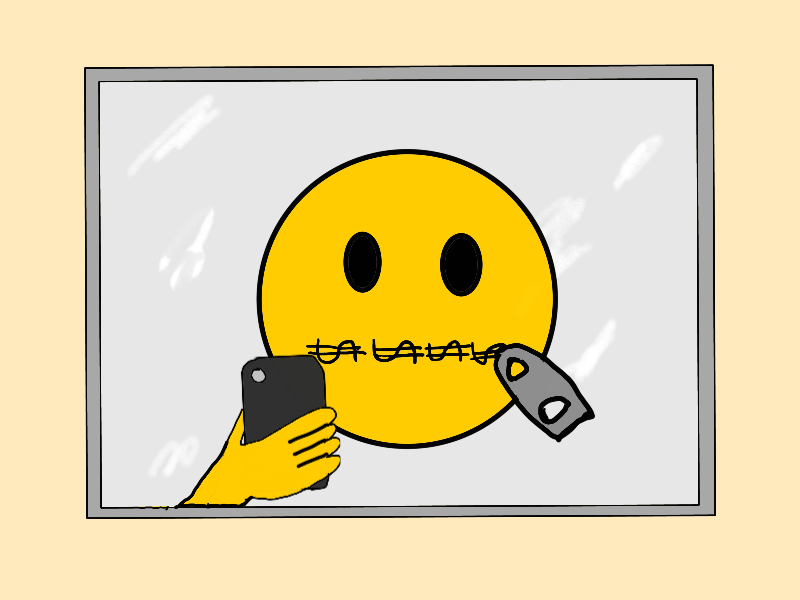

The real reason we don’t want to know or discuss our numbers is different: it makes it harder to lie to ourselves.

The way we indies describe ourselves to ourselves, and to a lesser extent to the world via our websites and social media profiles, is some mix of marketing, wishful thinking, and aspirational thinking. Looking too closely at numbers — even when we can’t easily compare them to others — tends to puncture our self-images in depressing and demotivating ways.

-

Are you really a “strategy consultant” or did 58% of your income come from intern-grade Excel-monkeying, and 37% from affiliate income, leaving just 5% of your income matching your claimed headline?

-

You might claim a half-dozen clients, but maybe 90% of your income came from one anchor client you dislike, for whom you do work that looks nothing like your headline, and you are more than a little embarrassed by.

-

Perhaps you claim to do “strategic brand narrative” work, but are really spending 90% of your time crafting clickbait email campaign headlines for a sketchy business.

-

Perhaps you claim to do organizational development for Fortune 100 companies, but that was one gig 3 years ago, and now you really mostly run a scammy online workshop for B-players at third-rate companies paying their own way.

-

Maybe you’re making a ton of money, but looking at the details of how the sausage is made reveals the utter meaninglessness of what you do, highlighting how it is actually worse on that front than the job you left for not being “fulfilling” enough.

There is a social aspect too. We indies may not compare lawnmowers across picket fences. We may not compare suits and ties on the trading floor of an investment bank. But we do compare, for want of a better phrase, online narratives and postures. We have our own version of keeping up with the Indie Joneses (heh!), where our Twitter bios play the role of the car in the driveway.

We know what sounds fake, and what sounds real, and have finely calibrated bullshit-detectors when it comes to parsing the public profiles of peers.

-

We can guess who’s putting on a desperate brave face, and who is understating what they’re making.

-

We can guess who is on the brink of penury, and who is on the brink of being able to quit paid work altogether.

-

We can see who is a grifter, who is a posturing snowflake, and who is really just a paycheck employee without health benefits.

-

We can generally pick out the people who are actually trying to do interesting and meaningful work. We can guess the extent to which they are succeeding.

Our version of the game would obviously be much easier if everybody shared more. But should we?

Is it perhaps a good thing that the game is as hard as it is? Do we actually want to be putting our current moving-average incomes on our Twitter bios?

Should you break the taboo and find ways to talk openly about how much you make? Or should you respect it, and learn the nuances of the game of keeping up with the Indie Joneses?

The Taboo is a Good Thing

This might be a surprising conclusion, but I think for indie consultants, as well as for paycheck types, the taboo is actually a good thing.

A richer, more functional social milieu exists because we have a certain sense of decorum around how we talk money. This sense of decorum is, in my opinion, wiser than the impulse towards what is generally a vanity form of openness.

In the case of indies, the important thing is to not lie to yourself, but the salary-equivalent number does not actually matter for its own sake. Unlike for paycheck types, it plays no meaningful role in your life. Since you don’t use it as the basis for negotiating anything, it doesn’t matter. On the other hand, component numbers of the illegible formula, like an hourly rate, are meaningless to compare on their own.

So for your own needs, the important thing is to develop ways of looking at your books that keep you honest about the questions that actually matter:

-

Does the headline of the work you claim to do match the contents? It is okay for there to be a gap so long as you understand clearly why it exists and should exist.

-

Does your income mix reflect your actual or desired posture? Both are fine — so long as you know which it is.

-

Are you doing too much of work you don’t want to, and too little of work you do want to? Are you able to say yes/no to gigs wisely, assuming you can say no at all?

-

Are you able to invest as much as you want in spec work and non-consulting income assets?

-

Are your finances lifestyle-optimized and tax-optimized?

-

Are you saving at a reasonable rate — like paycheck types, you too will grow old, less able to work, and needing to retire.

-

Should you accept this gig at this hourly or project rate? Will you learn something new that’s worth any discount you might be offering to land the gig?

-

Is your runway healthy? How about your health insurance situation?

-

Do your risks look good? Are you betting on things with a range of upsides?

-

Are there things you want to buy that you are not able to afford? Material quality of life matters.

The thing is, the paycheck-equivalent number doesn’t actually matter for any of these questions; it is a pure vanity metric of no consequence.

The only reason to want to know it is to have something to compare with others, and with your former paycheck self (and former colleagues still in that world).

So there is no personal reason to answer that particular question of paycheck-equivalent income.

What about social reasons?

We don’t play the keeping-up-with-the-Joneses game for neighborhood status, but we do play something that looks a lot like it, and it is not meaningless.

Learning to present yourself, and parse how others present themselves, is an important skill. You have to look enough like other people that potential clients understood who you are and what you offer (ie don’t call it “customer delight wrangler,” just call it “marketing”), and unique enough that they want to hire you specifically.

Part of learning this skill — and teaching it to newer indies who might find your experiences useful — is being able to talk compassionately and usefully about these things while being kind to each other, in terms of not overtly challenging the personas we all try to present and inhabit, where it would do more harm than good.

To the extent taboos foster healthy patterns of mutual support, they are good. To the extent talking about numbers out of vanity, some misguided sense of openness, or an inapplicable sense of solidarity, actually hurts others (by drawing them into unwise candor or demotivating them) violating the taboo is actively bad.

Reveal what you’re comfortable revealing, when and where you’re comfortable revealing it. You’re an adult. You don’t need rules/boundaries of the sort designed for children where thoughtfulness is called for. But you don’t need idealistic taboo-breaking for its own sake either.

It is entirely fine to tiptoe around sensitive matters with euphemisms and obfuscations. For example, I rarely ever share my income details even 1:1 with highly trusted friends (on the one day of the year that I actually have a sense of it), but I’m happy to share hourly rates pretty freely (but usually only 1:1) and advise others on where to set theirs, or how to price project-style bids.

I’m typically open about approximate narrative indicators like “I am making more than I did at my last job, but not as much as I probably would be by now if I’d stayed in it and progressed at the expected rate.” That sort of thing, I think, helps others calibrate in useful ways, and make their own quit/stay decisions.

It is somewhere between childish and clueless to hold to arbitrary standards of openness as a value for no good reason.

This is particularly a lesson struggling, early-stage indies need to internalize, because they often don’t recognize the costs of openness. Some seem to believe they have so little, they have nothing left to lose.

It is certainly okay to ask for help, even publicly on Twitter. It is okay to share some of what you’re going through. But there are costs. You don’t exist in a bubble of security and unconditional positive regard as you might within a healthy family. You exist in the real world, where what you say affects how you are perceived, and determines who is willing — or not — to deal with you. You exist in a world where visible vulnerability can be exploited.

There are real costs to posting a highly detailed confessional laying out all your deepest financial life secrets in the misguided belief that such openness will be seen as “authentic” and lead people to magically open doors for you.

That doesn’t happen. The world doesn’t work that way.

In the adult world, there is always a balance to be struck between vulnerability and guardedness, openness and discretion, managing perceptions versus presenting an unedited self to the world, solidarity with others, and pragmatic self-interest.

Wanting to be completely open financially — whether the picture is one of abject despair or obscene success — is more often an exhibitionist impulse or a reaching-out for human connection than it is a useful tactic in improving your financial condition.

So yes, talking about money is fraught — and it should be. Don’t let misguided idealism draw you into talking about money in ways that don’t feel either right or wise.