With Labor Day coming up in the United States, I’ve been reflecting on the big questions that affect us gig economy workers. These include what is perhaps the central political question in gig work, one that Labor Day is the perfect occasion to ask:

Are we gig workers part of labor, or are we part of capital?

For our purposes, “capital” is a loose category which includes the professional managerial/leadership class, as well as the share-owning class. Labor includes anyone for whom incentives suggest collective action as a good general strategic approach to achieving political goals, and whose share of capital ownership is too small to make a difference to their political goals.

So which are we? Capital or labor? The short answer is, we are neither. We constitute a separate emerging political class I call the clutch class. It is a politically loaded answer that I suspect will lose me a bunch of subscribers once I explain it, but so be it.

The New Class Wars

Besides Labor Day, two contemporary developments in the US make this question particularly salient and urgent right now.

-

In California, there is an effort underway (the AB 5 proposal) to make it much harder for companies to classify workers as independent contractors. Companies like Lyft and Uber are at the center of the battle. Proponents of the bill argue that rideshare drivers should be reclassified as regular employees. Opponents (including the companies) argue that most of these workers do not in fact want to be regular employees, since the flexibility of gigwork is what drew them in the first place.

-

There is movement on the other side of the management/labor divide as well. A group of 200 CEOs recently signed a letter proposing that all stakeholders, not just shareholders, should matter. In practice, this translates to “managerial class should have more power,” since they are the de facto representatives of all non-shareholder stakeholders, such as employees, customers, and the general public. It is a shot across the bows of activist shareholders.

In short, like it or not, a new kind of class warfare is getting started in the economy, and opening moves are being made by both the traditional classes.

Given the way politics around the world is shaping up, this war can only heat up in the next few years, not cool down. And the outcome will depend in large part on what we gig workers decide to do.

So where do we gig workers stand on the matter?

Well, that depends on where we sit, as one of my wise buddies, Carlos Bueno, likes to frequently remind me.

Where We Stand, Where We Sit

No matter which way you lean in terms of sympathies (I’m running a twitter poll on this, go vote), there is an objective correct answer: we are neither labor, nor capital. We are what I think of as the clutch class, in two senses of the term.

-

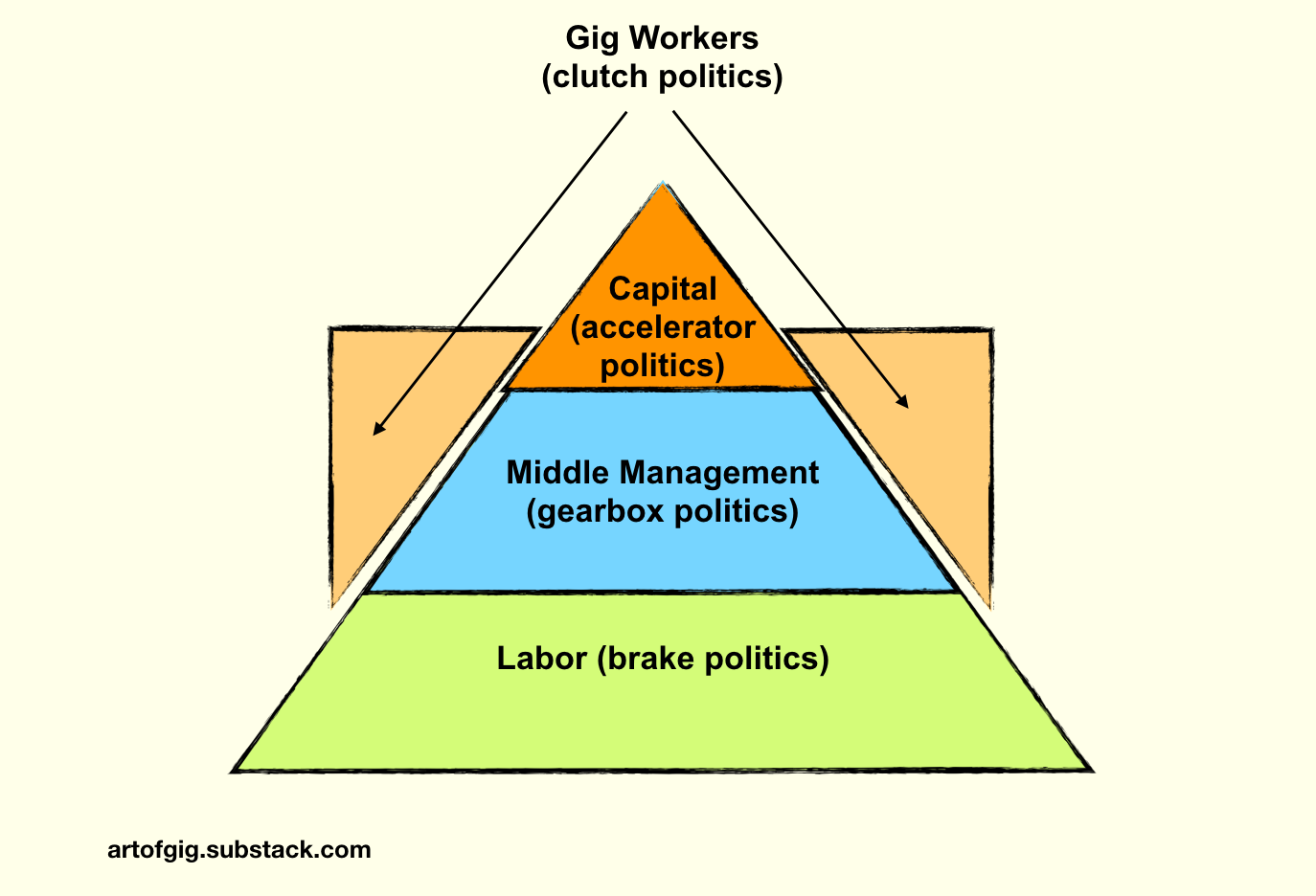

If you think of organizations as cars, a good mental model of the politics (not economics) of work is that capital is the accelerator, labor is the brake, and middle-management is the gearbox. And we gigworkers? We are the clutch. We help disengage/re-engage the drivetrain during gear-shifting, as operating regimes change and organizations need to adapt behaviors.

-

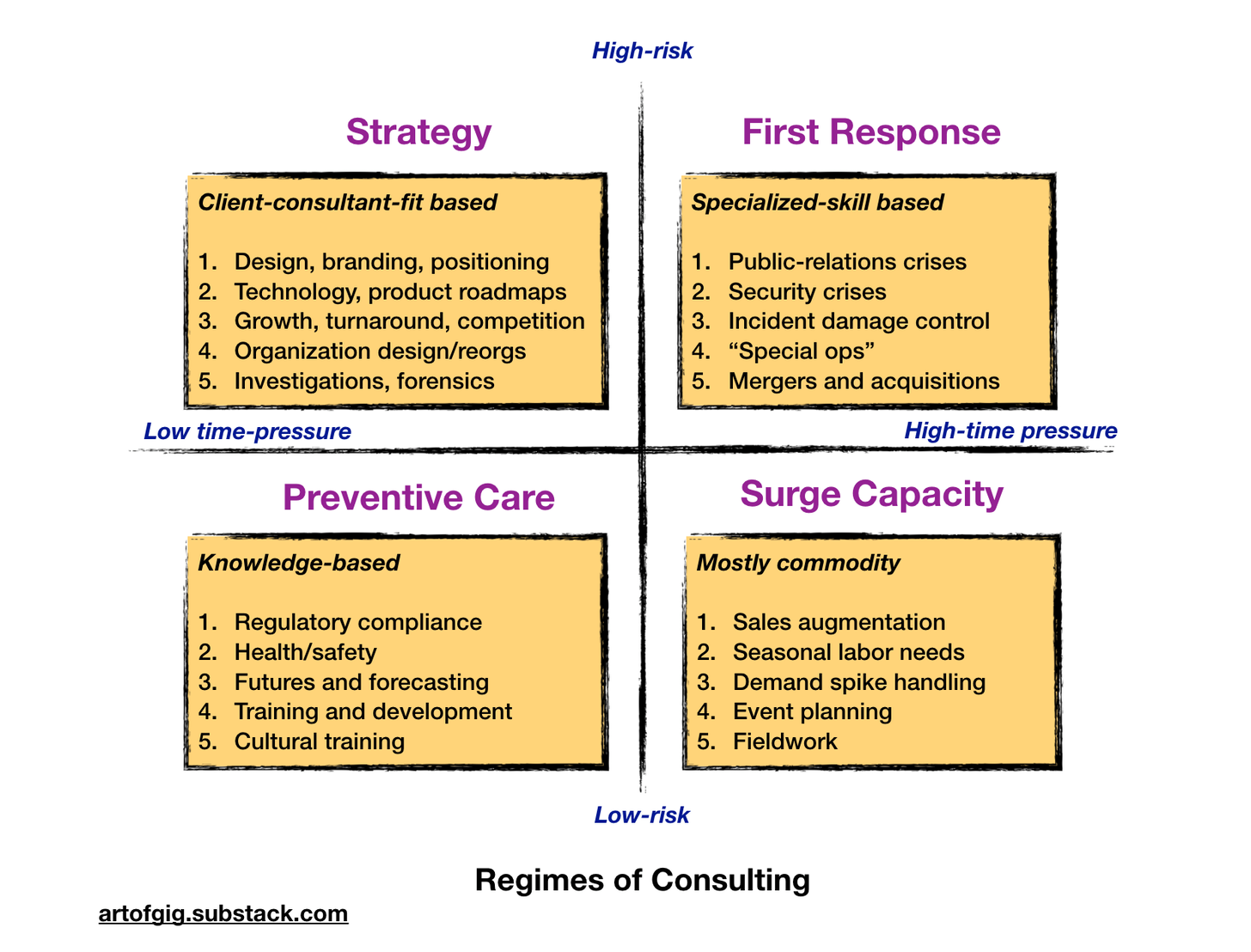

There is a second sense in which we are the clutch class, in the sense of the sports slang term: we are typically roped in to break stalemates and frustrating equilibriums, and actually make things happen and deliver some high performance during critical periods.

Both senses of the word should suggest a very uncomfortable relationship to labor movements and socialist politics.

Are We Scabs?

For a true socialist, the harsh view of us gig-workers who actually like what we do is that we are a generalized descendent of scabs.

This possible perception may or may not bother you (it doesn’t bother me), but it’s an interesting one to think about.

Though we don’t always act in ways that are against the interests of the organized (formally or informally) labor class that has incentives to organize for collective action, and meaningful mechanisms (though much weakened since the 70s) to act through, the default perception is…not wrong.

The defining characteristic of a scab is striking a self-interested independent bargain with the capital-owning/managing/leading class that breaks from any larger collectively bargained deal.

This defection does not have to be from a formal contract between an organized labor union and the managers/owners of a company. Even informal expectations around non-unionized jobs (including high-skill, high-education white-collar jobs, shaped by an elite culture of norms and conventions), are effectively an emergent collective bargaining outcome. The interests of individuals are subordinated to those of a larger group through various organic and designed mechanisms, and individuals generally go along with the collective flow, whether or not it’s led by union-type structures, and whether or not there are hard or soft coercive forces at work.

For example, a few years ago, when wage-limiting collusion was exposed in the tech industry, high-paid techies, not generally given to labor-like sentiments, were as outraged as striking factory workers. And that outrage had an effect even though it wasn’t channeled down traditional industrial action mechanisms. That kind of loose collective employee activism is becoming increasingly common around all kinds of political issues that affect workplaces.

This defining characteristic of scabs is also the defining feature of the gig-worker class. We defect from collective actions and trade off higher security, better benefits, and lower personal overheads, for two things:

-

More personalized working conditions built around desiderata that may not be shared by any larger group

-

Continuous, independent maneuvering capability where aligning interests with a group might require too much lock-step marching, or worse, voluntary social immobility

Why is this often hard for newbie gigworkers to understand? Because we share (especially early on in our careers) many of the practical problems that the most disempowered parts of the laboring economy face: precarity, periods where our income can be worse than minimum wage, health insurance risks, and little to no social safety net protections unless we pay full-retail prices out of pocket.

But these similarities do not make us part of labor.

High Agency, Low Capital

Though we share some of the problems (and have some of our own, such as a regulatory environment hostile to small/micro business structures), we don’t suffer from the same agency limitations in addressing them.

A graphic designer or independent strategy consultant is fundamentally a more mobile type of economic actor than a welder or an auto-assembly specialist. We work with our own cheap tools: laptops and notebooks for the most part, rather than with million dollar machine tools or billion dollar factories owned by investors seeking returns. We serve broad rather than narrow patterns of demand.

In the US for instance, a machinist with specialized training in operating a $20 million piece of equipment only used by big airplane manufacturers can pretty much only work within the Boeing or Lockheed ecosystems. A graphic designer not only has a lot more options, but owns her $2000 set of tools outright. A crane operator can only seek work in large industrial settings operating million-dollar cranes. A Lyft driver can work with his own $25,000 Prius.

It’s not that the incentives favoring traditional patterns of collective action in pursuit of political ends are absent, but they are weak. Too weak to allow for traditional top-down, explicitly organized collective action mechanisms. On the other hand, individual agency is much stronger. Much too strong to make coming together in solidarity with “others like me” an obviously smart thing to do.

Why, because the gig economy, especially the indie consulting corner of it, relies on production capabilities that are 5% based on owned capital equipment, and 95% based on affordances of the free internet.

The leverage of what little capital we own, thanks to the internet, is enormous. Bring your own device (BYOD), get your factory for free.

So yes, to a 1910s union firebrand, we are no better than traitorous scabs.

But from the perspective of a 2019 digital economy, we are members of the clutch class, who largely own our means of production, and have too high degree of agency in shaping our own lives to be part of labor, and too little wealth to be part of capital.

We are in the high-agency/low-capital quadrant of the economy (low agency/low capital is labor, high agency/high capital is capitalist class, low agency/high capital is groups like retirees).

This makes it worth our while to basically cut our own deals with whoever we can, whenever we can. Our interests do not generally align with any group that is cohesive enough, and constrained enough in choice of counterparties, that we are likely to wholeheartedly make common cause with traditional labor.

Incentives, Not Mechanisms

For a long time, I myself was confused about this. I thought there was a meaningful free agency collective-action mechanism design problem to be solved. I did not recognize that there was a fundamental misalignment of incentives all around, limiting the desirability of traditional collective action mechanisms and outcomes for us gig workers.

Though I’ve never been personally in a dire enough situation financially to have to resort to political actions, I’ve always felt a sympathy towards those who seem to often be in such dire straits. I used to think: maybe the rag-tag subculture of graphic designers needs a mechanism like the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) to work towards shared interests.

That was a flawed take. The rare corners of the gig economy where organizing like traditional labor is meaningful — actors are a good example — typically exist where the demand is concentrated enough that it can be targeted by collective action. And Hollywood has, until recently, been a very concentrated sort of industry. Now of course, that political balance of power between big movie studios and the talent market is shifting, thanks to the proliferation of cheap tools for moviemaking. Weird dynamics are being triggered too, perhaps as a result of the changing equilibrium (for example, the screenwriters guild recently initiated collective action against the agencies representing them, which is really weird).

With the right talents, you can make an excellent video with an iPhone, upload it on YouTube, raise money on Kickstarter, and make an indie movie on your own with rented equipment and non-SAG type actors. The value of various high-leverage distribution channels like movie theaters is falling by the day. From the point of view of traditionally organized gig-labor in Hollywood, I bet this sort of development comes across as a growing scab-like threat to their position. As yet, the threat is not serious, because the big streaming services do need the kind of high quality content that only Hollywood can currently supply. But that will change, and even Hollywood will be turn into collective action badlands (as an aside, it is weird that 20 years ago, when people first started talking about free agency, the “Hollywood Model” was often held up as an aspirational ideal; today it is becoming clear that it is an obsolete model to leave behind).

As a thought experiment, consider the challenge of actually unionizing in some Union 2.0 form, around whatever it is you do in the gig economy, and think it through a bit. You should get to reductio ad absurdum in a few steps.

Take me. As a strategy consultant who works with senior leaders, the very idea of joining up with fellow strategy consultants to form an Independent Strategy Consultants Guild, and trying to establish a defensible collective bargaining position relative to our shared client base — the tens of thousands of senior (typically VP+) executives in the world — sounds so silly, it looks like a bizarro parallel universe. If by some absurd miracle, such a mechanism came together, your best move would be to scab the hell out of it.

Something about the absurd picture of an ISCG guild president bargaining with a committee of execs in search of consultants just does not compute. Even the basic categories like president and committee are wrong. This is a not-even-wrong view of how at least this corner of the gig economy works.

And something similar is true of almost every sector where a lot of work is organized via the gig economy, one individual contract at a time, one 1099 at a time.

We are not labor. We are not capital. We are clutch.

We are clutch. We don’t waste time in bad equilibria, we either individually help drive discontinuous movements towards better ones, or we leave the scene for a better one.

We are clutch. We do not waste time on collective action political mechanisms. We let individual instincts guide us, and rely on emergent networked dynamics and the power of exit rather than voice to drive political change favorable to us.

We are clutch. We do not try to directly compete with capital by accumulating enough of it to be a player on that side. Most of us have lifestyle business goals — make enough to have a good life, but don’t kill yourself trying to become a multi-millionaire.

Mechanisms do matter, but the ones that we actually employ towards political ends are adapted to our political ends, not those of either capital or labor. The medium is the message.

For capital, the right mechanisms are based on catalyzing favorable regulations and market mechanisms for capital to seek the highest returns. The message of the medium is growth and acceleration. That’s right for them.

For labor, the right mechanisms are collective action based. The message of the medium is stability and security. That’s right for them.

For us in the clutch class, with our Slightly Scabby Tendencies, the mechanisms for working towards shared goals are much newer — loose, intelligent coordination around information advantages. We swap notes, we share leads, we pitch in to help each other out on specific gigs, we put ourselves in crucible groups to rapidly learn skills far faster than labor or capital, we serve as market makers in an economy of referrals, we do what needs to be done. And we do an end run around the stale battles of the 20th century.

The message of our medium is discontinuous change and maneuvering. Not growth for the sake of growth like capitalists, or stability for the sake of stability like labor.

And generally, we are hired by people aligned with the capital class, interested in driving discontinuous change, not by people aligned with the labor class (though there are gig economy cottage industries that are labor-aligned and active in certain highly regulated sectors like education and healthcare).

That’s what makes us scab-like. Whether or not you like that perception.

It’s a tough, harsh message for many, since the gig economy is full of people with strongly socialist economic sensibilities, deeply compassionate natures, and values based on solidarity, equality, and social justice, just like the labor class.

We do not like to think of our actions as perhaps betraying those values as embodied by certain older political forms. But I think we are true to those values in deeper, vastly more effective ways.

So push come to shove, where we stand depends on where we sit.

And in almost all cases, we sit right next to management and capital, serving as clutch players, helping shift gears where necessary, helping with surge actions, helping break out of stalemates.

And where we sit makes us scabs. The burden of that perception is something we have to accept. You’re not going to convince a traditional leftie otherwise.

Clutch Time

Let me end on a lighter note (too late you say? well maybe).

Labor Day is meant to commemorate the achievements and spotlight the political mission and values of the labor class. Those achievements, that mission, and those values are important, and matter. They should be spotlighted. More power to them. Happy Labor Day to them.

There is no Capital Day because you could argue that every 9-5 business day is Capital Day, and every big shopping holiday is Mega Capital Day. The mission and values of the capital class are also important, and matter, and should be spotlighted. More power to them. Happy Every Business Day and Happy Black Friday to them.

Is there a Clutch Day? A day for us in the clutch class to celebrate ourselves?

No, that sort of identity-centric performative class consciousness is for 20th century types.

The clutch class owns a dark slice of lived time rather than a day on the calendar. Clutch Time is evenings and weekends. With apologies to Chris Dixon, what the clutch class does on evenings and weekends, everybody will be doing in ten years.

Clutch time is when capital and labor both try to rest and relax, and gig workers get going. That’s the time when those of us in the clutch class really come into our own. We go to meetups, we get coffee with each other. We scan the social streams for openings, seek out room to maneuver, ways to deploy high-leverage cheap assets, learn break-out skills, dream up hacks and arbitrages. And we sneak one-at-a-time through gaps in the economy rather than marching rank-and-file in slogan-chanting cohorts.

We flow like water, shaping the landscape even as we get around it.

Generally making the stuffy old class hierarchy of the industrial age leak like hell, as we flow invisibly through the interstices, getting inside the OODA loop of the global economy.

Causing the world to shift gears.

We are not capital.

We are not labor.

We are clutch. And the future belongs to us 😎.