Independent consulting and independent investing share some tantalizing similarities. Both involve direct risk-taking, without an organization providing a safety net for you. In both, you have to strategize about returns that are not strictly causal functions of effort (ie you have to wrangle luck). Both are activities that inhabit a larger open-world economy of macro-trends and forces where you can try to go to where the action is, instead of waiting for the action to come to an organization that employs you. Both are unlike paycheck employment in that it is hard to blame others for “unfair” consequences. You have to own the results of your actions, good or bad.

But there are two crucial differences.

First, for investors, the primary input is capital, while for consultants, the primary input is time. Second for investors, the primary driver of returns is exogenous events, while for consultants, the primary driver of returns is the quality of your own actions.

Basically, as a consultant, you primarily create or destroy value directly, as a result of your efforts. An investor on the other hand, primarily banks profits or losses due to creative destruction happening out there in the economy.

As an example, take conducting a workshop versus executing a trade based on some information. A significant part of the returns from a workshop depend on the workshop itself being good or bad. For a trade on the other hand, the returns are good or bad depending on how the world actually behaves. You might have set up a technically perfect trade, but lose because the world does something else. Or you might have set up a sloppy trade, but the world does something that makes it a winning move anyway.

One clear way this difference shows up: As a consultant, you tend to win big when you do good, smart work that opens more doors, drives referrals, brings in more interesting and lucrative gigs, etc.

As an investor, you tend to win big when the world does stupid things. Legendary trades on Wall Street tend to happen in the context of crashes and meltdowns, where a minority presciently bet against the world.

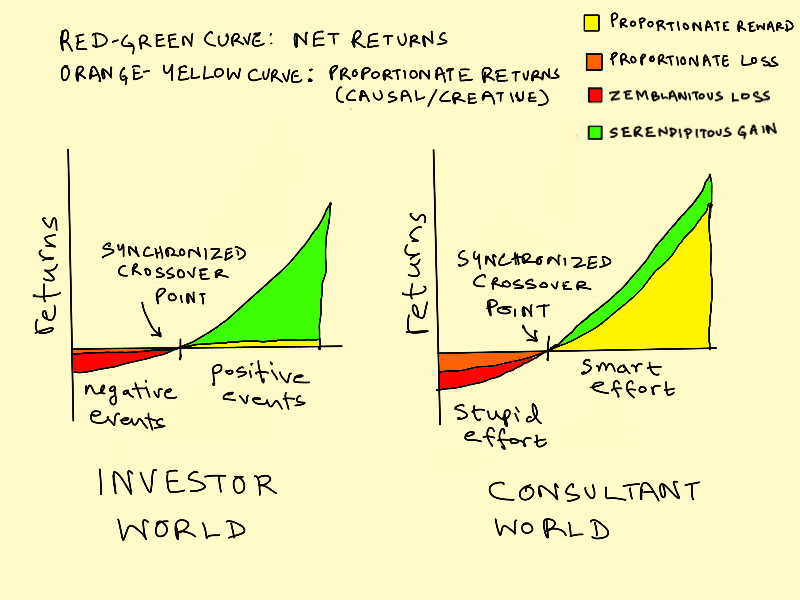

Investor World vs. Consultant World

Let’s capture these ideas in two graphs representing the investor world and the consultant world respectively. In both cases, there is a curve of proportionate rewards and losses (yellow-orange) where value is created or destroyed based on the quality of your effort (smart/stupid) and a curve of serendipitous/zemblanitous (“surprisingly lucky” vs. “unsurprisingly unlucky”). Here the red/green curves are the net return curves — the proportionate returns plus the effects of unexpected good or bad luck.

Here we’ve assumed a convex (what Nassim Taleb calls antifragile) world for both the investor and consultant, with increasing-returns upsides, and bounded-losses downsides. But the x-axis is different for the two cases. For the investor, the x-axis represents severity of positive or negative events relative to the logic of the trade. For the consultant, the x-axis is smartness or stupidity of the effort.

In both cases, we’ve assumed a synchronization in the crossover points for both proportionate consequences and luck effects.

The difference between the two worlds, as illustrated is twofold:

-

The x-axis is different (event quality vs. effort quality)

-

Relative proportion of proportionate returns (orange-yellow) in net returns (red-green)

(of course both event and effort quality apply to both, but I’m not about to plot a 3d graph here for what is already an outrageously cartoonish model)

As you can see, very little of the gains or losses of the investor can be attributed to the creative, causal effects of the trading actions. Trades do not create or destroy value by themselves (unless you’re a market mover like Warren Buffett, whose trades are read as “smart money”, implying quality, resulting in a premium). They allow value to flow from one part of the economy to the other, usually with a degree of entropic loss along the way.

Now that we have a basic picture in our head, let’s examine some varieties.

Four Consulting Regimes

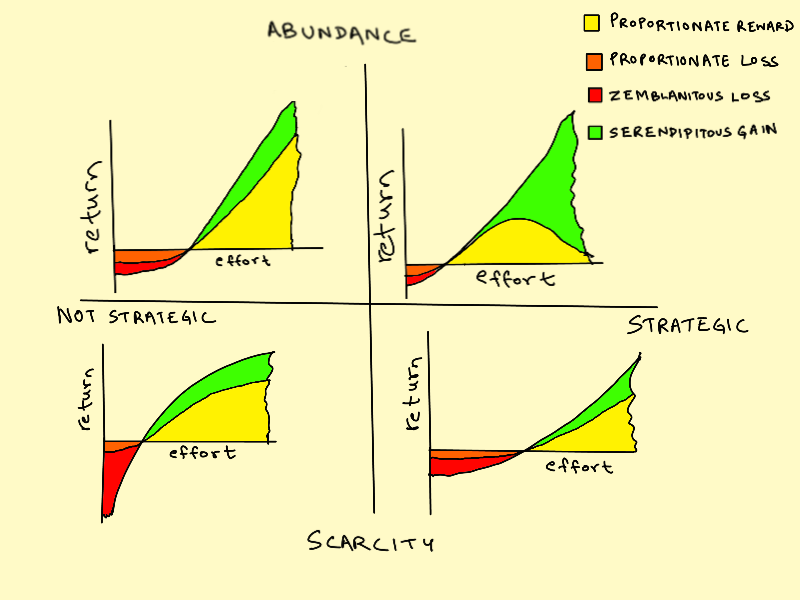

It is useful to carve up consulting activities along two axes: whether the environment is one of scarcity or abundance, and whether the consultant’s own actions are strategic or not.

Strategic is not the same as smart. Strategic means you’re taking advantage of being a free agent to constantly discover or create opportunities for yourself that would not be open to you as a paycheck employee confined to a single company. So for example, if you do a good project whose results are public, you can parley that into getting more gigs of the right sort at a better rate. Regardless of their strategic abilities, paycheck employees are limited in their ability to act strategically by the limits of their environment.

Here’s the 2×2:

There are four regimes here:

-

Non-strategic and scarcity: you’re exposed to non-convex conditions and high downside zemblanity risks. There will be little luck for smart effort, and highly compounded negative consequences for dumb effort (eg: drain your savings and then get hit by a health crisis with no safety net).

-

Non-strategic and abundance: conditions are nice, and you might enjoy a little luck with smart effort, and your downsides will be capped. Overall, it’s not that different from being a paycheck employee. Your gains and losses are just exaggerated a bit, due to higher exposure to luck forces. You’re neither benefiting too much, nor suffering too much, for being in the open economy instead of in the safety of a paycheck job.

-

Strategic and scarcity: The curve looks very similar to the diagonally opposite non-strategic/abundance quadrant, but here, there’s a chance you’re doing much better than paycheck employees at bad companies. You’re leveraging your freedom and strategic imagination to reshape a potentially default bad returns curve into a good one.

-

Strategic and abundance: This is what we’re all shooting for, a regime that’s unavailable to paycheck people, where net serendipitous returns on smart effort grow, even as the proportionate rewards get smaller as a fraction. If you go sufficiently far to the right, the proportion starts to look like the profile of investing activity. Your time becomes as good as money.

In my 9 years so far, I have spent significant periods in all four quadrants. Net, I’d say my average situation has been strategic-and-scarcity, but with some delightful periods of strategic-and-abundance.

In the scenarios above, we’ve continued to assume synchronization: that the world will get lucky or unlucky in lockstep with your actions getting smarter or stupider. This is of course the most unrealistic assumption.

In general, the crossover points for the “luck” and “proportionate rewards” curves won’t coincide. To steal a term from the printing world, there will be a registration error (the term comes from situations like printheads being misaligned, leading to different colored inks being laid down differently, leading to weird artifacts at edges).

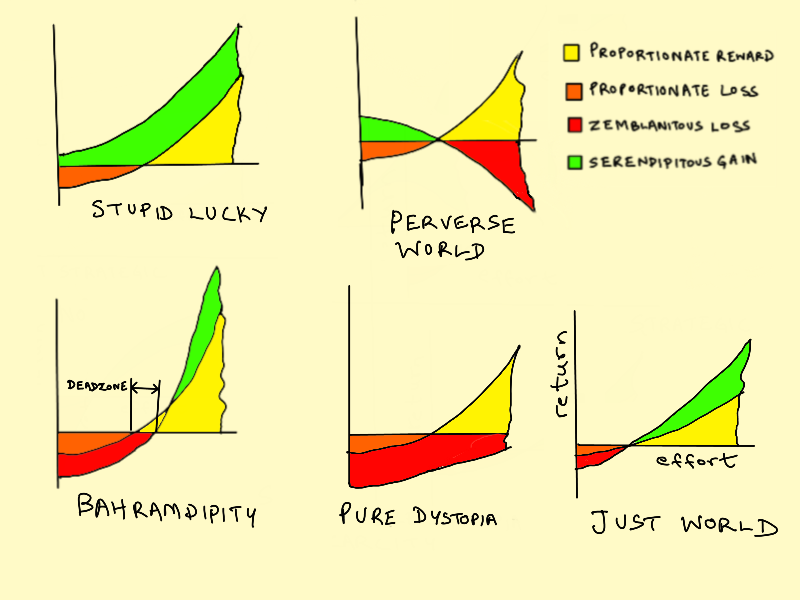

Misregistered Worlds

Let’s talk about worlds with registration errors. There are four kinds that you should be aware of (not on a 2×2 though):

-

A stupid-lucky world is one where whether your efforts are smart or stupid, you still win overall. The net returns curve stays safely above the x-axis, and a nice green band keeps you above zero returns. You actually have to think hard to find ways to lose.

-

A perverse world is one where smart effort actually leads to net mounting losses, while stupid effort is rewarded with net increasing gains. Be careful about jumping to the conclusion that you actually inhabit a perverse world. Most of the time, when the world seems to be acting perverse, it’s your assessment of smart/stupid in your actions that is backwards. That, or you’re being gaslit by someone with an agenda. Perverse worlds are actually rare. You’d be surprised how often people code their actions backwards because they can’t tell stupid and smart apart, and therefore project it as perversity onto the world.

-

A pure dystopia is the opposite of a stupid-lucky world, where whether your actions are smart or stupid, the proportionate gains and losses are always swamped by overwhelming bad luck. There is always a red band of pain, and you’re always underwater, taking net losses.

-

Finally, bahramdipity refers to a world that is fundamentally serendipitous, but malign forces try to kill the serendipity. This means that up to a point, positive smart effort will still lead to negative returns. But if you push hard enough, you might overcome the malign forces and start winning. So there is an effort deadzone where there is a proportionate positive return (the little yellow wedge near the crossover point) that is swamped by a negative environmental drag.

There’s a lot more you could do with these effort/return diagrams and parsing of luck effects vs. proportionate effects, but I’ll stop here. I’ve already built a rather wobbly edifice here, on the strength of a rather shaky analogy between investing and consulting.

Ultimately, the graphs and notional varieties are just scaffolding for thinking about luck, smarts, strategy, and environments. If you don’t like thinking in terms of convexity and effort/event vs. returns curves, you can reframe it more simply as a set of lessons about how best to invest in yourself. So I give you…

Consulting Like an Investor: Seven Principles

-

Independent consulting is like independent investing, except that you’re investing time into the quality of your own efforts rather than capital into beliefs about events in the world.

-

Going independent is giving yourself permission to be strategic, and putting yourself in a playing field — the broader labor market — with opportunity for strategy, just as investing is putting yourself into a broader financial market than your local bank.

-

Because you’re primarily investing time rather than capital, strategy is about quality of effort you put into your creative output, not the nature of events.

-

The winds of good and bad luck are often, but not always, synchronized with the smartness or stupidity of your actions. Be attuned to this synchronization state.

-

Strategy is a lot more consequential under conditions of scarcity, to reshape default bad into default good returns curves, but the relative positive returns of free agency primarily accrue when you figure out how to be strategic in good times. Strategy under scarcity makes survival as a free agent possible. Strategy under abundance makes survival as a free agent worthwhile, and preferable to paycheck employment.

-

Being strategic is not the same as your efforts being smart. Smart vs. stupid is about what you do within a gig. Strategic vs. not-strategic is what you do between gigs.

-

The world is often in a state of misregistration, and you have to be sensitive to four kinds of environment in particular: stupid-lucky, perverse, dystopian, and bahramdipity. Inhabit stupid lucky worlds if you can, and bahramdipitous ones if you must. Get the hell out of perverse or dystopian environments as soon as you can. 80% of strategy is putting yourself in the right environment. 20% is about what you do there.