There’s a joke I like that illustrates the foundational role of knowledge in consulting work.

Guy takes his car to the mechanic because it is making a mysterious noise. Mechanic opens up the hood, and tightens one nut. Mysterious noise gone!

“That’ll be $50,” says the mechanic.

“Hey!” the customer protests, “All you did was tighten one nut! How is that $50?”

“Let me print out an itemized bill for you,” says the mechanic.

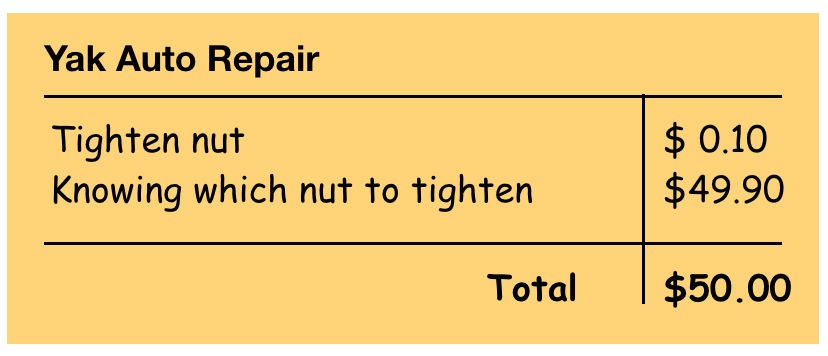

The itemized bill:

Knowing which nut to tighten to resolve a mysterious noise is a simple example of a knowledge asymmetry. In this case, the knowledge was everything. The mechanic didn’t bring any execution skill to the party. He could have “consulted” on which nut to tighten for $49.90 and the customer could have done the “execution” themselves, saving $0.10.

This is often the case in consulting. The execution skill is often either trivial or available in-house in the client organization. The entire value lies in knowing which nut to tighten.

Knowledge Asymmetries

The joke illustrates two features of knowledge asymmetries.

On the one hand, it highlights the value of knowledge asymmetries. Knowing which nut to tighten is, in a sense priceless. Somebody who does not know which nut to tighten will likely waste hours trying to figure out the problem, and possibly do dumb things that make it irreversibly worse. In the worst case, the cost of the unfixed loose-nut problem might be the whole car being lost in an accident, possibly with loss of life.

But it would be a general waste of cognitive resources if everybody knew enough about cars to solve the loose-nut problem, which might occur in one out of a hundred cars over its lifetime. It makes sense for a few specialists — preferably people who have self-selected into car repair because they like the work — to know about the mysterious-noise/loose-nut connection, and do the nut-tightening for everybody.

On the other hand, the joke also illustrates the obvious potential for abuse, hinted at in the opaque “knowing which nut to tighten” claim. The mechanic could easily have screwed around doing nothing for hours or even days, made needless repairs with expensive parts, and finally done the nut-tightening as well. The customer wouldn’t have been any the wiser.

Worse, even if the mechanic doesn’t do that, how does the customer know that $49.90 is in an appropriate price for the “knowing”? Would other mechanics charge the same? Was the knowing the result of something you might learn in a weekend auto-repair course or the result of 30 years of experience and pattern recognition training? Is it a reasonable mark-up on amortized learning costs? Or rent-seeking?

These problems, of course, are aspects of the famous principal-agent problem.

While it is inherent to all knowledge work, the principal-agent problem is particularly acute in any relationship where the typical principal has a need that is rare enough that there is no incentive for them to get systematically knowledgeable about the domain, while fulfilling the need is so common an activity for the agent that they have incentives to learn to do it very cheaply, systematically, and efficiently.

A personal example: my “sparring conversation” model maps to a type of conversation I tend to have once every week or two with a different client. So I get 25-50 practice sessions a year. But some of my lower-frequency clients (often C-level execs at mid-size companies who have to do all the high-level thinking for their companies on their own) tell me that I’m the only one they have such conversations with, so their frequency is perhaps 1-2 times a year.

Knowledge Asymmetries for Employees

The principal-agent problem does affect regular employer-employee relationships, but is not as severe for several reasons:

-

A manager — the internal “customer” for the work of an employee — is likely to have done the same kind of work before being tapped to supervise it

-

The relationship is longer-term and higher frequency. It is harder to hide the nature of a problem when an instance is being detected and solved every week.

-

There are likely peers with the same kind of knowledge, and strong incentives to rat out a fellow employee who is exploiting principal-agent knowledge asymmetries

-

Much of the asymmetric knowledge is actually in proprietary systems rather than in the heads of particular employees

As a result of these factors, in work done by employees, there is a visible, reasonable-seeming correlation between effort and problems. And in general, the more important the problem is judged to be, the greater the cost of the effort.

This is not an accident. It is practically the definition of an organization: a collection of systematically monitored, high-frequency activities defined by reasonable-seeming correlations between effort and output.

In fact, you could argue that the core competency of organizations is knowing — at an codified process level — roughly how much effort it should take to accomplish any of a vast array of core activities they can do better than outsiders, and setting compensation policies accordingly.

If you’re one of those people who likes to analyze firms in terms of Coasean transaction costs, this effect can be seen as lower monitoring costs in a relationship. An employee is simply cheaper for an organization to monitor for dishonesty or ineffectiveness than an infrequently used consultant.

A much-worse-than-average employee (in terms of either dishonesty or incompetence) will soon be spotted. A genius employee who routinely finds 1-minute solutions to problems that take peers days will either be promoted to work on the hardest problems, or have their thinking skills analyzed and turned into teachable disciplines for non-genius employees. They are likely to turn into teachers themselves, trading the asymmetric knowledge for esteem.

The net effect of these two feedback loops is that behaviors that do not exhibit a reasonable-seeming correlation between effort and output either get weeded out or tweaked until they do.

What’s more, this dynamic also makes it harder for the firm itself to be dishonest the larger it gets, because more people with agent-side participation in knowledge asymmetries have to collude (so a “tell” of a possibly shady firm is a great deal of internal secrecy between groups that minimizes the number of people with complicity in any given deception).

Any employee with a very unique, opaque, and illegible skill is a huge risk for an organization. To prevent such an employee from falling prey to principal-agent temptations or being poached by a competitor, they are likely to end up highly compensated, so that it is simply not worth their time or energy to exploit the asymmetries of their knowledge.

Often a uniquely skilled but underutilized employees, despite being compensated enough to make dishonesty uninteresting, will end up leaving and becoming a consultant simply to find more things to do.

Reasonable Efforts for Reasonable Output

I’ve used the relative phrase reasonable-seeming rather than the absolute reasonable to describe the perception of effort in tasks done by employees.

Therein lies a subtlety. The work of an organization is a theater of apparent reasonableness that may or may not be actually reasonable depending on whether or not the foundational assumptions for the internal reality of an organization are actually true.

Quite often, these assumptions are at least slightly out-of-date. Often, they are wildly, insanely obsolete, in ways that are obvious to outsiders. Internally though, the organization may be unconsciously pumping a massive amount of energy into denying what’s obvious to outsiders. It may take serious social courage to challenge the “consensus of reasonableness” in the internal economy of valuing efforts and outcomes.

On the other hand, outsiders can be very, very wrong in interpreting the externally visible behaviors of an organization, in which case, reasonable-seeming is actually reasonable in an absolute sense, and it is the world outside that is insane in its beliefs about what “reasonable” looks like.

In some cases, there is no way to easily tell whether the organization is deluded, or the external world is deluded. The best you can do is think hard about it (from either side of the organization’s boundary) and wait for the judgment of history.

In either case though, one of the tells of an organization working very hard to maintain an internal reality that is dissonant with respect to external perspectives is resistance to consultants.

When the internal reality is deluded, consultants might inject an entirely unwelcome reality check.

When external reality is deluded, consultants might contaminate a fragile island of deeper truth by injecting bad external thinking.

In either case, we consultants represent informational risks and threats to the organizations we try to help, and it’s generally up to us to manage the risk.

Neutralizing Your Risks

This entire system breaks down in areas where the organization does not know enough to efficiently deploy as employee knowledge but has a strong (possibly rational) resistance to plugging knowledge gaps using consultants.

Consulting begins where monitoring costs get too high, relative to need frequency, for employees to be the right answer.

That doesn’t mean the monitoring cost problem goes away. It tends to get solved in varied ways:

-

Crisis-only consulting policies: Organizations will simply resist retaining consulting services unless it is a crisis and the cost of not bringing in outside expertise to help become unacceptable. These companies simply leave the risks of non-crisis knowledge gaps that cannot be addressed by employees unmanaged.

-

Ecosystem competency: Organizations will consciously develop competency in managing an ecosystem of consultants via specialized monitoring mechanisms — think certification programs.

-

Externalize the risk explicitly: Many organizations will require consultants and contractors to carry specialized insurance policies, as some of you will know. I’ve never yet taken such a gig.

-

Relying on exceptions: Many organizations will have default no-consultant policies, but allow senior executives to make exceptions based on special needs and the existence of trusted relationships. This of course, is an entry point for a lot of cronyism.

In my experience, the most common approach is the first one, leaving non-crisis knowledge gap risks unmanaged. Approach 2 works where there is a skills base that the organization can control and shape in some way (such as by owning the core design of a product). Approach 3 passes the buck to the consultant.

Last week, I took a lot some cheap shots at the economics-inspired positioning school of consulting. This week, I tried to give you a glimpse of how an economics lens can sometimes be useful in understanding how to approach gig work. The conclusion to draw from this, however, is that your best approach to creating trust and getting good gigs is Approach 4, ie a people-school approach to a problem whose structure is illuminated by a positioning school analysis.

Build relationships that allow you to be an exception to anti-consultant rules/barriers. So long as you keep yourself honest by resisting the lure of cronyism and only taking gigs where it is clear that you’re bringing genuine external knowledge or relationships to the party, it is the best way to address the legitimate principal-agent concerns of clients, without bearing too heavy a burden of externalized risk-management costs yourself.