I was dealing with a family medical emergency for much of this week, so this week’s issue is rather grimly inspired by personal life stuff. Naturally, it’s in the form of a 2×2, my own preferred first-responder protocol.

I came up with this while trying to figure out why my response to events this week seemed inadequate even to me, and even by my own mediocre-slacker standards. I concluded that what I deal with poorly is the combination of high risk and high time pressure.

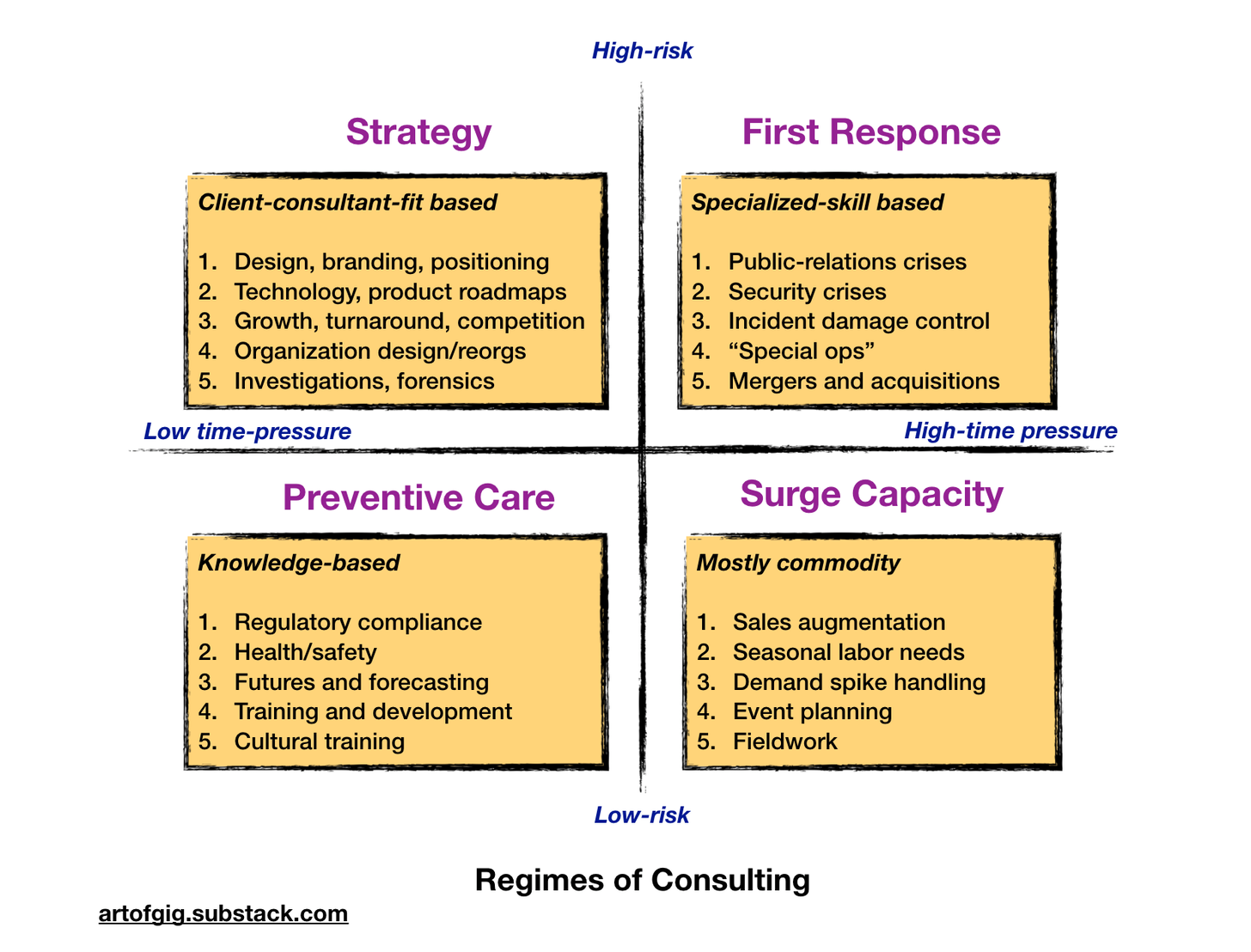

These seemed like good axes for thinking about regimes of indie consulting as well (especially for corporate clients; this week’s issue is not quite as relevant for those of you who work primarily with individuals), so I figured I’d explore the time-pressure vs. risk 2×2. It is a cousin of the well-known important vs. urgent 2×2 (the Eisenhower matrix, popularized by Stephen Covey), but the shifts in variables helped me think more clearly about responses in particular.

Viewed from a time-pressure/risk perspective, the roles of consultants of all types can be understood as participation in non-routine institutional response patterns.

Commonplace and specialized capability shortfalls in generating such responses are generally met via standing B2B relationships with other companies. One company’s consultant is another company’s paycheck employee. This kind of response capability, available as an on-demand service from another large firm or organization that has effectively aggregated enough demand to smooth out variability and sustain a separate corporate existence, is not for us indie consultants.

So where do we indie consultants fit?

We help address capability shortfalls that fall through the cracks between in-house capabilities and systematically outsourceable capabilities.

Indie consultants naturally fit in where the capability gap is either small enough and oddly-shaped enough to be filled by a few individually contracted people OR where the gap is large, but can be filled by a fairly generic type of labor without the help of a labor-aggregating counterparty.

Extra-Institutional Response Patterns

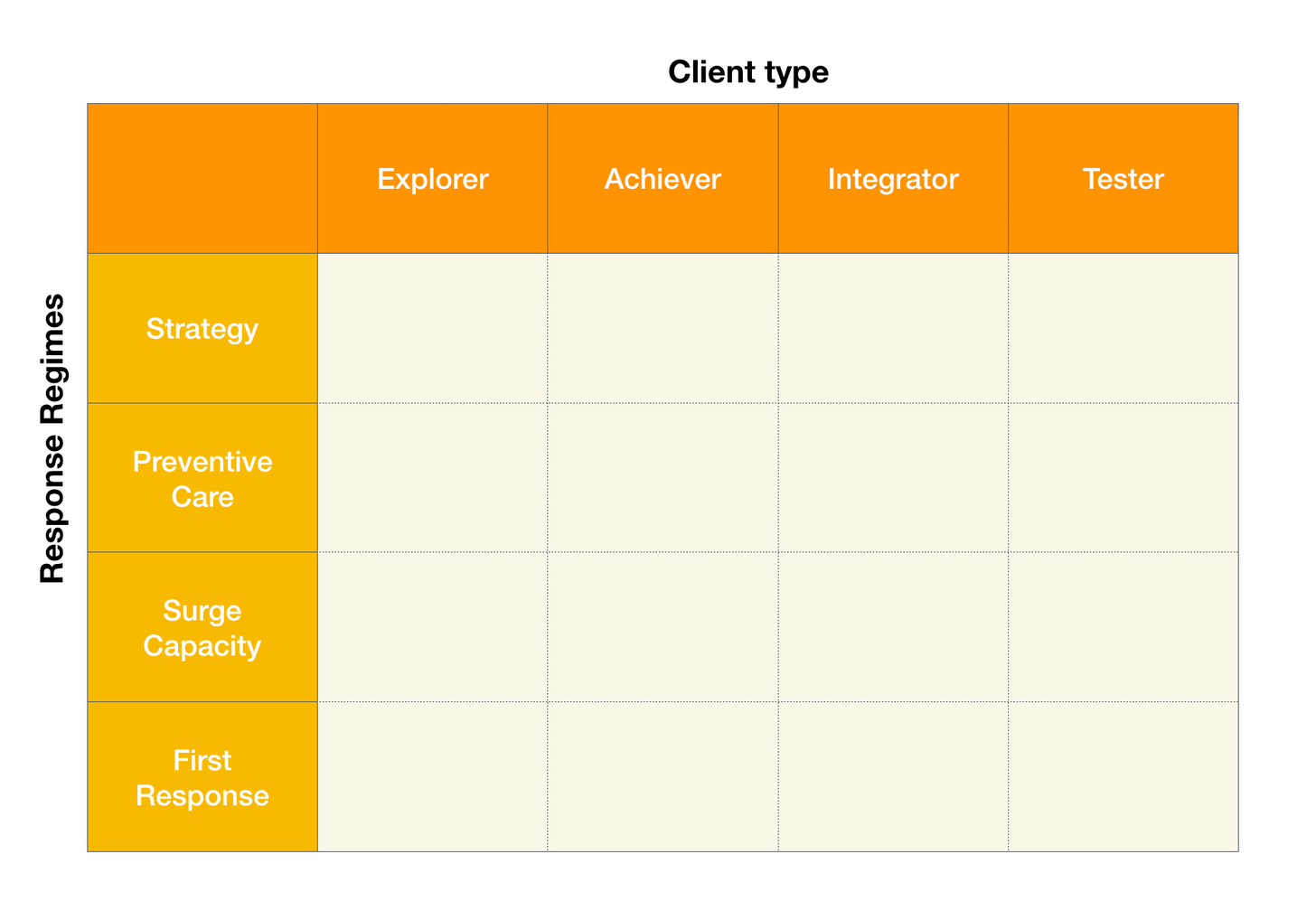

In a previous post, Elements of Consulting Style, I outlined 4 styles based on 4 types of clients. This response regimes 2×2 gives you an alternative set of 4 styles, based on 4 types of situational response you might be helping clients craft.

If you apply both 2x2s to what you do, you’ll likely end up with a very good triangulation of who you are as an indie consultant. I’d be interested to hear where you land, in the comments. Your offering might fall into any of the 16 types induced by the two 2x2s. I for instance offer “Strategy for Explorers”. You might be in “Preventive-Care for Integrators” or “Surge-Capacity for Testers”. Here’s a handy 4×4 table for you to think about. Try classifying the gigs you’ve done or would like to do on it.

Indie consultants help client companies generate responses to events and situations for which they lack an internal capacity, and which they do not understand in a systematic enough way to outsource to another large company (indeed, aggregator service providers may not even exist in sufficiently messy and treacherous capability minefields).

In other words, indie consultants are part of extra-instutional response patterns. That much is obvious.

What is perhaps less obvious is that the lack of systematized capability (either in-house or outsourced) is generally rational. Perhaps the need arises infrequently, or unpredictably. Or perhaps it is a one-and-done deal in the median case, like logo design. Or perhaps there is a glut of supply, making it easy for companies to just hire what they need, when they need it.

Curiously, many struggling consultants seem to believe that the lack of in-house capacity for the services they offer is irrational. That their work ought to be a job, and that they ought to be hired in as an employee to do it. I’ll save analysis of that phenomenon for another day. It leads to weird and potentially crippling mental blocks that put you in the worst of both worlds.

Let’s survey the 4 types of extra-institutional response.

Preventive Care

The low-risk, low time-pressure quadrant is a very crowded (for obvious reasons) and demand-limited market. It is also something of a lemon market: bad actors driving out the good.

It is easy to convince yourself — and certain kinds of gullible clients with more budget than sense — that all sorts of preventive care consulting products and services are necessary. This is the kind of consulting offering (often made up by laid-off mid-career middle managers who have succumbed to up-or-out pressures) that best fits the accusation that consultants are people who help solve problems that wouldn’t exist in the first place without them.

Preventive care is usually a knowledge-based consulting offering, and the main principled question to ask is whether the knowledge is useful or necessary for the client.

If you have to struggle hard to sell the value of the knowledge, and it feels like lecturing someone who may not have teeth to floss regularly, you might want to reflect on how necessary the knowledge you’re hawking is.

You might want to ask yourself honestly what the actual risks and costs of ignoring the knowledge (and you as the bearer of it) are, for the client, and why they seem to be getting along fine without it.

Perhaps your prospective clients are not quite as dumb as you think for turning down your proposal for a two-million-dollar all-hands 12-step Alien Attack Preparedness workshop (box lunch included).

Surge Capacity

The high time-pressure/low-risk quadrant is the commodity quadrant of consulting. If consultants are being hired in job lots, driven largely by predictable or unpredictable demand spikes affecting the client, it is surge capacity. If you feel like part of an “Uber for X” work force hanging around hoping for surge pricing to kick in, you might be in this quadrant.

If you’re in this quadrant, chances are you’ll struggle to brand and position yourself uniquely, and also struggle to set your own price or differentiate yourself from contract labor supplied by contracting companies. One test: you have a blog, portfolio site, or other marketing asset, but most of your work still comes through gig sites like Upwork. You’re unable to actually attract any work at your preferred bill rate, and are forced to work at prevailing market rates.

Note that the “low risk” part is at the individual level. For a company that needs to temporarily double its sales force to exploit a seasonal demand surge, the opportunity costs of missing the big selling window overall may be huge, so in aggregate, the response may be a high-risk one. But retaining a given individual consultant is not a high-risk move, since there are many participating in the response, and any individual consultant is dispensable/easily replaced.

Strategy

This quadrant is generally where I hang out, though I make the occasional foray into the preventive-care quadrant. High risk and low time pressure is generally the combination of conditions that makes anything “strategic”. Things that end up in this quadrant are generally the most thinky types of consulting offerings, but surprisingly (and unlike the preventive care quadrant), are not strongly knowledge or skill based. Instead, they are based on client-consultant fit and trust.

While knowledge of course plays a role in strategy-centric offerings, it is usually based on a rich but illegible track record that induces trust, and idiosyncratic personal mind-melds of taste and intellectual style between client and consultant. Since there are no skills per se, beyond general intelligence, and there is generally enough time to read and research relevant information, knowledge matters less than the ability to connect with the client’s capability shortfall in an effective and trustworthy way.

A good strategy consultant is, in many ways, simply someone who is good at just being present in a situation without becoming yet another part of the problem. This can be surprisingly hard to do (many a time, I’ve watched “strategy” people walk into a messy situation, and pick out, with unerring accuracy, the role to occupy that makes them biggest new piece of the problem).

Sometimes, all I do in a situation is listen and bear witness to whatever is going on, occasionally drawing attention to this or that piece of the puzzle, adding nothing new. I’ve received the most appreciation when I manage to do that well. It’s kinda fun working in a zone where “great, you didn’t make it worse!” is rare enough to be appreciated.

First Response

This is the quadrant that, I learned from this week’s events, I’d probably be bad at. I’d put stuff like security or PR crises there. The combination of high risk and high time pressure imply that it is a zone where there is no time to learn, or even translate knowledge into actions via deliberate analysis. You have to be able to pattern-match and generate appropriate responses much faster.

Not just that, you have to be good at dealing with clients in abnormal states, like patients in ICUs. Their ongoing behavior may be shock or stress driven, and be entirely inappropriate and unskilled. Their regular functioning may be severely compromised by the situation. They may be a big part of their own problem. The situation may involve various other parties who have become involved, like law enforcement, disaster relief, or the media. Deep emotional reserves may be necessary for effectiveness.

I’d like to learn and get better at first-response behaviors, and the art of adding value under significant time pressure. I think one of the reasons I turn to 2x2s so often is that it is genuinely a first-responder triage-style tool, though I don’t often get to use it in first-responder ways. It’s a sort of aspirational thing with me.

First-response consulting is now one of my research interests. If you think you’re in this quadrant, I’d love to hear from you in the comments (and I suspect other readers would too). If you have interesting references to books or blog posts in this quadrant, I’d love to see those as well.