Into the Yakverse index | Prelude: II >>

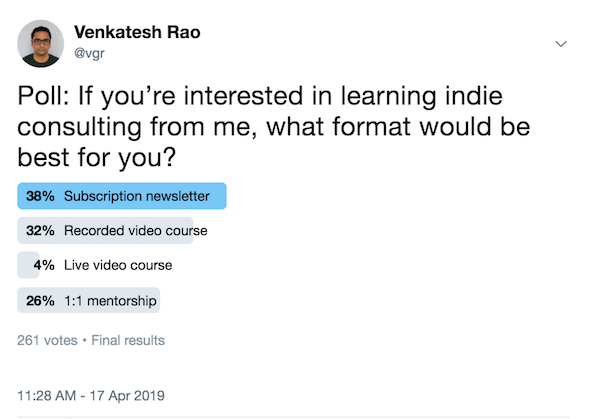

I don’t talk about my consulting gigs much on this blog, since there is surprisingly little overlap between my money-making work and my writing. But many people seem to be very curious about precisely what sort of consulting I do, and how that side of ribbonfarm operates. Unfortunately, it’s hard to explain without talking about actual cases, and I can’t share details of most engagements due to confidentiality constraints. But fortunately, one of my recent clients agreed to let me write up minimally pseudonymized account of a brief gig I did with them a while back. So here goes.

It all began when my phone rang at 1 AM on a Tuesday morning a few months ago. The caller launched right into it the moment I answered.

“Oh thank God! Donna has the ‘flu…I tried calling Guanxi Gao, but I can’t reach him. I left a message but… omigod, we’re going to run out of inventory by Friday, what are we going to do?”

If you aren’t used to the consulting world, this is how most engagements begin: you’re dropped into a panicked conversation in the middle of a crisis that has already been unfolding for sometime.

Luckily, I was not yet in bed, but doing some routine Open Twitter Operations from the Ribbonfarm Consulting Command Center.

I hit the red alert button on my desk, which turned off all but one of the 16 flat-panel displays that line one wall of the darkened main room of the RCCC. The one that stayed on showed a blank 2×2 grid with a flashing lemon-yellow border. The speakers switched from Mongolian throat singing to a steady pip…pip…pip.

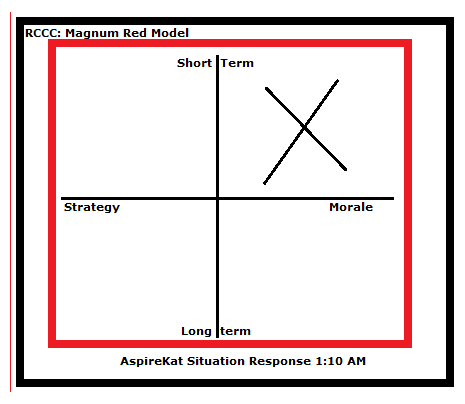

Many consultants today use more complicated first-responder protocols, but I am old-fashioned. One clean vertical stroke, one clean horizontal stroke, at most 10 quick labels, and you’ve got your Situation all Awared-Up in the top right. 75% complexity reduction in minutes.

Ten seconds into the call, and I was already set up to Observe, Orient, Decide and Act. This is the sort of agility my clients have come to expect from me.

I interrupted the frantic speaker firmly. You have to interrupt panic calls to do a basic assumptions check. Many gigs get derailed simply because somebody does not take the time to figure out who they are talking to, and about what.

“Who is this? Do you mean Donna Dauntless, VP of Radical and Disruptive Strategery at AspireKat? We haven’t worked together in years.”

“Yes, sorry, I found your name in her emergency contacts list. This is Ben Bean, her admin.”

“And what are you running out of, Ben?”

“Thought Leadership. We only have enough inventory to last through another 24 hours and… omigod omigod, I forgot, we have a projected 312% Employee Disengagement Spike on Thursday because of that Pharell concert in the evening. Omigod, what are we…”

“Now calm down. Where is Donna and what is she doing?”

“I swung by her house. She’s all hopped up on Nyquil and making still-life paintings. I don’t think she’ll be in again this week.”

I sighed and moved a slider under the 2×2 all the way to the right. The border turned to a steady red. There goes my week.

“Okay Ben, now l want you to calm down. I am going to send you a triage 2×2 and you’re going to put that up on all the displays on the executive floor. Can you do that for me? Then I want you to take a nap right there in the reception area. We’re going to have a tough few days. I’ll head over as soon as I can, and we’ll get on top of this.”

There was an audible sigh of relief from Ben.

“Oh thank you. Should I try Guanxi Gao again…?”

“No, never mind that, I know him well. We’ll rope him in later if necessary. Just put up the 2×2 and seal off the executive conference room until I get there.”

You booze you lose, Guanxi. It felt good to steal a gig from the jerk after a long time. Hah!

I stood up, stepped back, and stared at my empty 2×2 grid. After a few minutes, I decided to go with one of my standard first response 2×2 templates, the one I call Magnum Red: Morale vs. Strategy, Short-Term vs. Long-Term.

With a quick flick of my wrist, I spun it around to put the Morale/Short-Term in the top right, added a large X there, changed the caption to AspireKat Situation Response 1:10 AM, and hit Send.

That should get them breathing again. I leaned back and did a quick 30-second Refactoring Meditation.™

I was Oriented and ready for action.

***

If you have never seen a live Consultant First Response unfold, you probably don’t know just how ugly things can look before people like me step in to clean up the mess created by incompetent leadering.

In retrospect though, I should have chartered a plane and flown in, as I sometimes do on high-value gigs, instead of riding my bicycle. That might shaved two hours off my trip, and made all the difference, as you will see.

Anyhow, things were not looking pretty when I stepped out of the elevator on the executive floor of the AspireKat headquarters at 6:30 AM.

The entire senior leadership team was gathered in front of the reception area monitor on the left, staring at my Magnum Red 2×2 and nodding to themselves occasionally. Good. Several were nervously fingering their Apple iRosaries. They were breathing heavily and sweating, but mostly seemed to have regained their composure.

Nobody was lying down on the half-dozen or so mattresses that somebody — probably Ben — had thoughtfully laid out along the far wall, across from the elevator.

That much I expected.

What I did not expect was Guanxi Gao. By the glass wall on the right, next to the large potted plant, a red-eyed, unshaven Gao was talking earnestly to the CEO, Saul Serene. Saul is balding and about 60. We had never interacted in person, and he’d grown a goatee since the last time I’d seen him, when I was working with Donna Dauntless. He was dressed in a calming black turtleneck, slacks, and rimless glasses.

He was looking through the glass wall at the dawn skyline view with noble, stoic dignity. Not entirely Dead White Male. At least 1/128 Native American, I guessed.

Guanxi, in a cheap, wrinkled suit, was swaying slightly, holding a large travel mug of his coffee in one trembling hand. He was trying to get Saul to look at a piece of paper in his other hand. I couldn’t make it out, but it looked like a list of names.

Goddamit. I thought I had that handled. You do not expect Guanxi Gao to be up and sober enough to operate this early. Oh well, I could handle him sober. He is mainly a threat when you’re shadow-boxing for a gig after the fourth drink. After the fourth drink, who-you-know people win 90% of the time against what-you-smoke people like me. I don’t smoke of course. I’m one of those rare natural imagineers.

There was one more surprise for me as I finished my scan of the reception area. In the waiting area on the right, on one of the comfortable armchairs, sat young Arnie Anscombe, tapping away rapidly at a laptop. Charts and tables were flying around on his screen. He seemed to be using a lot of keyboard shortcuts, always a Dark Magic danger sign.

Now this I had not expected at all. This had just turned into a three-way battle. There was a what-you-know player in the ring.

Worse, like me, he was impeccably turned out in doer-stubble and a nerd-normcore sweater. Except that he could actually wrangle data, while I was, truth be told, faking it and exploiting Standard Assumption About South Indians #17.

I’d have to play the Indian card differently now to stand out, with him around. I ran a hand through my hair to make it look more curly, and mentally reset my accent to 23% more Indian. Enough to come across as International Management Bagman of Mystery, but not enough to be mistaken for lowlife outsourcing broker.

I had run into Anscombe before. He was at least 15 years younger than either Guanxi or me, and hadn’t yet found his niche. But the last time I’d run into him, in a dirty skirmish in the solar cell industry, I had discovered how dangerous he could be.

He could crunch entire Big Data stores in the time it took me to rotate a 2×2. Real-Time Falsification ran through his damn digital-native-born veins.

Technological leverage. That was the key to his value over aging Gen-Xers like me. Guanxi, sober or drunk, I could mostly handle. Anscombe, not as easy. He represents a new breed. They form a sort of ISIS-like threat in the indie-consulting world.

But you know what was ironic? Anscombe stole that solar cell gig from me not with a data-driven insight, but with a 2×2 based on dummy data! One whose axes did not even make sense. This was not going to be easy. I should have had Ben lock down the IT system too. Oh well.

I looked around for Ben. Clearly, that would be the anxious looking young man standing by the locked executive conference room door with yellow caution tape across it. His gaze was darting fretfully back and forth between the main huddle and Guanxi and Saul. He seemed to be ignoring Anscombe, another bad sign.

I cleared my throat, preparing to announce myself. But before I could, Anscombe looked up from his laptop.

“I’m in.” He announced.

The reception area monitor flickered, and then switched from my Magnum Red 2×2 to a split display with two graphs. One showing real-time employee engagement, the other showing real-time customer sentiment mined from Twitter. There were also two scrolling feed columns, showing Twitter mentions and a Slack #general channel.

Double damn. Derailed by Dynamic Data yet again.

This called for decisive action.

“Alright everybody, let’s get going. Ben, you can open that door now. And hold it open please! Nice little headstart you’ve gotten us there Anscombe, thank you. Great to have one of you young analytics gophers on board! Should help add a little extra kick here!”

***

To my relief, Magnum Red was still showing on the conference room display.

I managed to maneuver Saul to the head of the table and position myself by the display at the other end of the long room, with the stylus prominently visible in my right hand.

The rest of the executives seated themselves around the conference table. Guanxi and Anscombe were left standing by the back wall. Fortunately, we were exactly three chairs short. Sometimes the universe works for you.

“Thank you Ben. Saul. Gentlemen. Ladies.”

I looked around the room, then stepped to the side with my stylus raised and looked expectantly at Saul.

“You want to get us going, Saul?”

See, this is the critical moment in consulting. Executives of course have no idea what they are doing, ever, so the economy really runs thanks to consultants like me. And if I am being fair, professional alcoholics like Guanxi and analytics-gophers like Anscombe.

Without us, the world would crash and burn within minutes. Trust me. I’m telling the truth. Not like some of those other consultants out there who won’t tell it like it is.

But you have to let executives think they are in charge. With the right cues, they do the right thing.

Saul, however, did not do the right thing. He hesitated, looked uneasily at Ben (who was sitting in the chair closest to me, looking relieved) and then pulled the one CEO move that strategy consultants have nightmares about.

He swiveled his chair away from me, triggering a cascade of swiveling.

Double Deadly Damn it to hell.

And as I had immediately dreaded, he swiveled, not towards Guanxi, with whom he’d been chatting, but towards Anscombe.

“That graph…”

Goddamit. I had misread Saul. His security blanket was not models, not relationships, but numbers.

Fortunately for me, Anscombe’s inexperience betrayed him. Incredibly enough, he looked away from Saul and turned to look at me. That, my friends, is the power of being The Guy with Control of the Whiteboard. Even if you’ve put the wrong first response up on it.

I bestowed a paternalistic smile upon him. Candy from a baby. I turned to rapidly work on the board.

I erased the big X in the top right quadrant of the Magnum Red, wrote BACKSTOP in large red letters and double-underlined it. Beneath it, I put, in parenthesis, (employee engagement?).

In the bottom left quadrant, I wrote: customer sentiment — Anscombe?

I made sure the lettering in that quadrant just a little bit smaller and harder to read.

The room had gone quiet while I was writing, and everybody had swiveled back to face me. I stepped back to admire my handiwork, then turned around and smiled at Saul.

“So…shall we talk priorities?”

He opened his mouth, then closed it again uncertainly.

That was the opening I needed to take control. I jerked my head upwards and to the right, and put on the expression known in the industry as Real Time Insight, Executive Suite Edition.

Back when I was a rookie, I used to get things mixed up. Sometimes, I would turn sharply and take a few decisive steps across the room, which is what the industry calls Real Time Insight, On-Stage Edition.

Sometimes it doesn’t matter if the room is large enough, but in a small room, even a few decisive steps can have you stopping abruptly and awkwardly at a wall, which just makes you look like an idiot. So a professional performance really requires you to have the entire contents of the Consultant’s Complete Body Language Reference (2nd Edition) in muscle memory.

I now had their complete attention. Whether they realized it or not, they had just subliminally reacted to the arrival of an Insight in the room, via yours truly.

I held up my hand dramatically.

“Wait a minute… I think I have an idea about how to structure this!”

I paused, then very deliberately turned my back on the room to face the display. Always Be Channeling attention. ABCa.

I pulled up a clean sheet in the whiteboard app, and drew a large green circle in the center. Then I paused, and drew a larger dotted triangle around the circle, in blue.

I labeled the circle Executive Team and added Saul at the center. Then I added Rao, Guanxi, Anscombe at the three vertices of the triangle, being careful to put Rao at the left vertex and Guanxi at the top vertex. In the past, I would have labeled the vertices Ideas, People, Data as well, but I’ve learned that you never want to put yourself in a boxed-in structure, no matter how attractive and conceptually elegant it is.

You only do that to other people. Otherwise people start classifying themselves into being for or against you. You want to leave people free to do pattern-spotting and self-classifying to their heart’s content, but not call out any patterns or classifications that make you more legible.

The key with effective whiteboard work, especially when you’re using FUD-wrangling constructs chosen because they are unfamiliar to the audience, is to recognize that even if people think the element near the top is the most important, they behave as though the leftmost one is most important.

Because they read left to right. I once lost a major gig in Dubai because I hadn’t yet figured this out. The Sheikh was very nice about it, and gave me an oil well as a consolation prize, but it stung.

I stepped back with a satisfied look, smiled benevolently around the room, and looked at Saul.

“You’re the backstop here of course Saul, and the buck stops with you, but I suspect it would be useful to have your team first sign up for whatever pieces they can turn around quickly.”

See, the key to working with the nominal Top Dog in a situation is to craft a Situational Control Structure™ or SCS,™ within which they can feel powerful, like they have both authority and authoritah, and appear to have accountability and humility as well, but not actually do anything.

A good leader, when asked, “Do you want to be perceived as a Strong Big Man Leader or a Humble Servant Leader” will always reply “both,” and mean “neither.”

If you can keep the Top Dog happy, everybody else falls in line. At the same time, you do not want to lose the subtext that keeps you really in charge, but not accountable to anyone. But this is much easier than you might think.

The key is to deploy a calibrated amount of Buzzword-Bingo Lingo™ to both direct attention to the right places and trigger conditioned responses. Too much, and people check out. Too little, and you have chaos.

The maneuver I used, reinforcing the single world Backstop across two whiteboard panels, and connecting it to a Heroic but All-Sacrificing Lonely Leader stance role for Saul to occupy, is what is just one of many used in the business. The overall maneuvering of people into situational roles and events into plotlines, the core of consulting tradecraft, is called massaging the narrative.

The purpose of this is to ensure that everybody except you loses the plot, but feels like they’ve actually grasped it better. The first few bits of massaging you do should be designed to create the right level of urgency. Backstop is a word that suggests a situation that is somewhere between an unmanaged crisis and a tough, but in-control war-room. It is a word that wakes people up and makes them feel all virtuously focused, but doesn’t incite any actual precipitate action.

This is called Determinacy Illusion Engineering™, or DIE.™ Together, SCSing and DIEing constitute 60% of all consulting work.

I tilted my head at Saul and got the nod of assent I was looking for.

“Let’s go back to the situation matrix. How about we start with…?”

I looked at the woman to the right of Saul.

“Lopez. Isabella Lopez. EVP of Operations.”

We need to stop and unpack what I did there.

See, you should always begin Structured Conversation Operations™ or SCO™ (another 30% of strategy consulting) with a gesture of transparent, but not overt, inclusion signaling.

If you start the SCOing in a logical place, such as with the person who knows the most about what is going on, people might start actually thinking so much they no longer need you.

But if you start with a gesture like this, people turn on a socially appropriate ritual mind, which involves a certain useful level of thought suspension, compliance and self-censorship. You can stop entire lines of second-guessing and unfriendly counter-proposals dead in their tracks by creating the right ritual context. Of course, you can’t go nuts with this stuff and expect it to work. Asking the token black intern in the room taking notes to get the ball rolling would be way too transparent a move.

If you know what you are doing, you can deweaponize Social Justice Warrior techniques and turn them into useful civilian management tools. And identity performance is just one of the many useful and powerful cultural forces you can harness for use in modern management.

But it’s a mistake to trigger ritual cultural behaviors openly, with ceremonial cues like “let’s make sure everybody feels heard here.” You want to cue socially programmed robotic behavior without people realizing they’re behaving with 34% more ritual circumspection than they intended to. Here, I started with the person on Saul’s right, but I could have gone left, started at the other end of the table, or used any number of other defensible starting points, and people would have explained it to themselves as a logical choice using any creative rationalization except race-and-gender.

“Great, Isabella. Let’s start with you, and since us folks on the triangle looking in from the outside haven’t met all of you, perhaps you could all introduce yourselves too? What we need is for you to estimate how much Thought Leadership you can generate quickly…Ben, how much do we need to get us through the next week? I assume Donna will be back by Friday?”

Ben looked up, startled. He had been anxiously looking at a calendar on his phone.

“Err… I don’t know. We have a dozen slides to get us through the rest of today and tomorrow, which should just be enough… but Thursday, with the projected disengagement spike… I really don’t know.”

“Give us a guesstimate. You are going to have to quarterback this, and you’ve done it before, so think.”

See, here is a subtlety that many rookie indie consultants miss when it comes to SCOing. You have to figure out who is going to be conscripted to take point on a situation, and it usually can’t be one of the executives. Because if there’s one skill people invariably pick up on their way to the Executive Suite, it is the alertness to never take point on a situation that they do not have the freedom to define.

Even the greenest of new VPs gets this instinctively, even if they cannot articulate it. They will resist Responsibility without Autonomy with all their might.

So the key is to tag someone who does not recognize the age-old anti-pattern of asymmetric tactical contracting (a bastardized version of what consultants intent on using Big-German-Word-FUD call Auftragstaktik): You decide how to lead, I’ll decide what sort of control structure you’ll be using.

You also have to make sure the person you maneuver into position has the right mix of haplessness, suggestibility and susceptibility to flattery. If you operate in the United States, the phrase you’re going to have to quarterback this does the trick. Even with women. Especially with Leaning-In Women. Picks out the right person every time. The metaphor is not a useless flourish: it is just as much a part of the Situational Control Structure™ as the role-casting you do with executives.

Clueless consultants use explicit, abstract and functional role and responsibility definitions. They even think it’s their job to make these up. The worst ones even go so far as to draw block diagrams to illustrate theirideas.

No, no and NO.

That’s HR-sideshow stuff somewhere in the middle of the staff hierarchy. The lowest kind of consulting.

The strategy consultant’s job is to prime senior executives and their staff with just a hint or two, so they end up using Situational Control Structures™ that benefit you, while imagining they thought of it themselves. Not only does it work better, it buys you more plausible deniability if things don’t work out, since you can’t be blamed for a documented process suggestion.

That does not mean you don’t have meta-control over the process of getting an SCS™ off the ground through the Structured Conversation Operations™ that you’re using to drive things. Quarterback gets people thinking along very different lines than priming words like say, Captain or Consigliere or Steward.

In India or the UK, you’re going to open the batting will work. In continental Europe or China, this sort of hard-charging Anglo-culture maneuvering does not work, so you need other moves that are much more collectivist in spirit and more we and us pronouns liberally thrown around. Soccer metaphors help, but I am not very good at those. But whatever the local culture, there are always appropriate metaphors and triggers you can use to massage the narrative.

One way or the other, you need to find a Ben and get them out in front of the crisis, ready to be The Face of the Situation.

Ben looked uncertain for a second. I smiled encouragingly. He sat up straighter in his chair, leaned forward with his fingers steepled and spoke confidently for the first time.

“I’d say we need about 34 Thought Leadership slides by Thursday morning. The disengagement spike is going to be pretty big, so we might even want to consolidate them into a Vision Deck to cascade through the whole organization before lunch. And possibly a three-point communication email from Saul. Donna always has Saul do a three-point communication email during disengagement spikes.”

Perfect.

I turned to look at Isabella. She opened her mouth to speak, and at that point, all hell broke loose.

First there was the din of a helicopter coming in really, really close.

Next, there was a loud sound of breaking glass.

Before I could say a word, everybody began rushing out.

***

The entire glass wall of the reception area, with the panoramic view, had been shattered.

Men in gray suits and combat helmets, carrying genuine leather messenger bags, were rappelling down a rope dangling just outside the broken windows, and swinging into the reception area.

Three had already taken off their helmets and set up their laptops in the waiting area. A fourth, an immensely tall man carrying a large Viking battle-axe, was barking orders at the men streaming in, directing them to different setup locations.

We all stood, mouths agape, as the last of the dozen or so men swung in. The rope vanished upwards and out of sight. The helicopter dropped down into view for a moment. The pilot gave a thumbs up to the tall leader of the suits and stylishly banked the helicopter away, with thoroughly unnecessary drama.

The din subsidized. The immensely tall leader put aside his battle-axe and stepped forward towards Saul, with a reassuring smile and his hand extended. His suit looked just a little bit classier than the others’ suits, and he was not carrying a messenger bag. Just a large phablet in his left hand. Could he be…

“Hi Saul, Ulysses Alexander Khan. McKinsey Engagement Manager. You can call me Khan. Let’s head back in there and get started.”

KHAN! I had heard of the legendary McKinsey EM before, but had never met him. It was rumored that he had undergone gene therapy that allowed him to structure conversations just by staring down people in a particular order, without saying a word. I didn’t believe these rumors, but I had to admit: the man was impressive.

Before I could speak, he had steered Saul back into the conference room, with a reassuring hand on his back. The rest of the team followed them immediately, glancing back over their shoulder at the now buzzing reception area, their eyes wide with wonder.

Guanxi, Anscombe and I looked at each other. Then we turned to look at the McKinsey team, who were ignoring us.

Anscombe said, “What the…? Why the hell are they crashing such a small gig? This isn’t even going to break 100k in billables…”

Guanxi looked uncertainly at the busy team, who had now occupied the whole reception area.

“Should we just join…?” he began uncertainly.

I cut him off. “Of course not. We’re not hanging with the flunkeys. We’re going back in there.”

Saul looked relieved when we walked in. Khan was looking at the screen with amusement, twirling the stylus in his hand, waiting for the room to settle down. He smiled sunnily at us and gestured us towards the back of the room.

“You’ll have to stand for the moment, I’m afraid. I’ll have one of my people bring in more chairs in a bit.”

Bastard.

He turned back to the display.

“A 2×2, how charming!” He swiped to bring up my triangle-and-circle graphic.

“Wow, a Type 9c circle-triangle Platonic! Haven’t seen one of those since consulting bootcamp back in ’88. Very creative. I am constantly impressed by how well the little rag-tag indie outfits manage to get by with so little. We professionals could learn a thing or two from them.”

He turned around to look at Saul.

“Very nice work under the circumstances. The VP of Radical and Disruptive Strategery getting the flu in the middle of a Thought Leadership crisis is nothing to sneeze at. I suppose it’s one of those gentlemen at the back who has been helping you frame things so far?”

Saul looked uncertainly at Ben, who looked uncertainly at me.

“Dr. Rao here is helping us structure the conver…”

Jeez, thanks Ben. Way to just HAND the guy the Ignore-the-Impractical-PhD card.

“Not anymore, he’s not,” Khan interrupted, his tone was friendly, but with an edge of hard blue steel showing through. “McKinsey is in the house. We’ll take it from…”

Now, I can generally hold my own even when open hostilities commence, but I am not very quick on my feet right after a shock-and-awe entrance by one of the Big Three. If you’ve never experienced one of these, being on the receiving end is a little bit like being suddenly drunk.

Close up, helicopters are really loud. They know this, which is why, back in the 90s, the Big 3, along with most of the larger boutique firms, switched to rappelling down from helicopters instead of parachuting in from planes.

Rappelling also has the advantage of being more accurate. Back in the day, the Big 3 used to lose a lot of deals simply because half the Engagement Team would sometimes lose control of their parachutes and land miles away from the client site. They’d just give up and head to the nearest restaurant offering a three-martini power-lunch (a thing in those days). The big firms found themselves losing more and more engagements to jumped-up IT consulting outfits, while accumulating power-lunch expenses that could not be billed to any client.

Now they have it down to a science. They know that in the first few minutes of shock and awe, even the most battle-hardened CEO can be counted on to go along with the laziest of Big Three framings.

Fortunately, it was Guanxi’s moment to shine. He stepped forward, staggering only slightly.

“I think,” he said with the raspy and over-careful enunciation of the still-hungover, “Isabella was just about to give Saul her situation assessment when you guys joined us.”

Khan looked nonplussed. He had overplayed his hand. Guanxi had bought me just enough time.

I lightly stepped around to where Saul could see me.

“If you agree Saul, since we now have the resources of a full-scale McKinsey tactical team here, we should perhaps have Mr. Khan explain their operational set up out there to Isabella first, and have her decide how they can be integrated into her operations?”

Saul nodded immediately. I had finally begun to anticipate his responses correctly. Saul was fundamentally a chain-of-command guy.

“And it might be useful to have Mr. Anscombe here join them, since he’s already got a handle on the relevant disengagement spike data?”

I figured I might as well use the opportunity to test the youngling’s alignment instincts. If he managed to work himself out of the safe but low-leverage box I had him parked in for now, and choose sides wisely, interesting things could probably happen. And I needed wildcards in the picture now.

When faced with overwhelming force, start building unpredictability into the situation at every opportunity. Momentum is your enemy. FUD hurts everybody involved, but it hurts the biggest, highest-momentum guy the most.

It was also important to keep Anscombe safely in play, since it was already clear that Saul needed a Data security blanket.

See, in a FUD-and-counter-FUD situation, many people think the key is knowing who needs what kind of security blanket.

That’s a key, but not the key. The key is knowing who can provide any given kind of security blanket that might be needed, even if it isn’t you, and getting your candidates front and center at the right times. Saul was comfortable enough with People equations to stay on top of Guanxi by himself. He was a question mark on Ideas.

But he clearly needed to know where he was with Data, and needed help doing so.

He had been been looking baffled for several minutes. Now he switched to looking dazzled.

“Great idea. Brilliant!” he said to me, getting up decisively. “Lead the way Bella.”

Khan looked at me and glowered. But he had lost the plot for the moment and could do nothing, and he knew it. I had even managed to stick the tactical label on him, and he hadn’t been able to react quickly enough to prevent that. That had to sting, especially for a McKinsey vet. Shock and Awe aside, it was Little Guys 1, Big 3: zero. But I knew that wouldn’t last.

We filed out again, with Khan leading the way and Isabella and Anscombe right behind him.

Guanxi and I brought up the rear, straggling a bit.

He leaned over to me and whispered, “We should get a drink next time we’re in Hong Kong at the same time.”

***

Khan’s team of suits was now lined up in a row, at attention, saluting stiffly. Their helmets were back on.

“ASSOCIATES, Report!” Khan barked.

The suit on the far left of the row goose-stepped forward.

“Sir, Spreadsheet Team is Go, Sir!” he yelled.

The rest began stepping forward in turn.

“Sir, Primary Dazzler Systems are Go, Sir!”

“Sir, Secondary Baffler Systems are Go, Sir!”

Anscombe was staring at the equipment bank in the waiting area with his mouth open. I could see why he was impressed. They’d brought in a full-scale 128-core Welch-Jobs Dazzling Scenario Generator and a state-of-the-art Mitsubishi Baffler 3000, capable of piping customized FUD into 3000 screens at once.

As Anscombe had observed, this made no sense. It was overkill.

With this setup, they’d blow through a standard 72-hour Thought Leadership Crisis consulting budget in about 12 minutes. Clearly they had smelled something bigger.

Khan and Isabella were now by a bank of screens with several spreadsheets open, and he was BigThreeSplaining something to her. This was going to take a while.

I sidled up to Saul.

I whispered, “Looks like Isabella is on top of operational preparedness, and looks like Khan and his people are tactically set up to execute on any creative ideas we might throw at them.”

Saul nodded. Twice labeled. Khan was safely in the tactical box for the moment.

He said, “How about we get back in there and work the strategery in parallel? Get ahead of this thing instead of reacting to it?”

BAM!

The first sign Saul was not entirely averse to Ideas. And he’d gone there entirely by himself, without me having to work him there.

Things were looking up again.

See, in strategy consulting, the greater the quantity of resources you deploy into an engagement, the lower down the hierarchy you go. Pyramids are bottom-heavy, so resources are not necessarily an advantage, since they need a certain amount of pyramidal breadth to operate within. They get you in quicker, but they weigh you down later.

The guy who gets control of narrative is often the guy operating with just a whiteboard, right at the top. No Big Data. No spreadsheets. No PowerPoint.

Just a man and his whiteboard, armed with nothing more than a germ of a 2×2 in his head. Consulting in all its elemental rawness.

Saul stepped back from the group and headed back towards the conference room.

I gestured to Guanxi to follow. We were on the same side now and we both knew it. If he passed the test, I’d reel Anscombe back to our side too, after he was done being Tech Dazzled.

Us little guys were down for the count, but not out yet.

Into the Yakverse index | Prelude: II >>