I’m going a little out-of-order in writing this series on executive sparring. In The Guru Factor, I teed up a deeper dive into the sorts of appreciative knowledge that prepare you for sparring, but I’ll table that for a future post and tackle something I think needs to come first: the assumptions you must make about yourself, the client, and other people in constructing what I call the problem social graph, which is the foundation of sparring. This is the configuration of other players in the organizational context relevant to the problems the client is trying to solve through sparring.

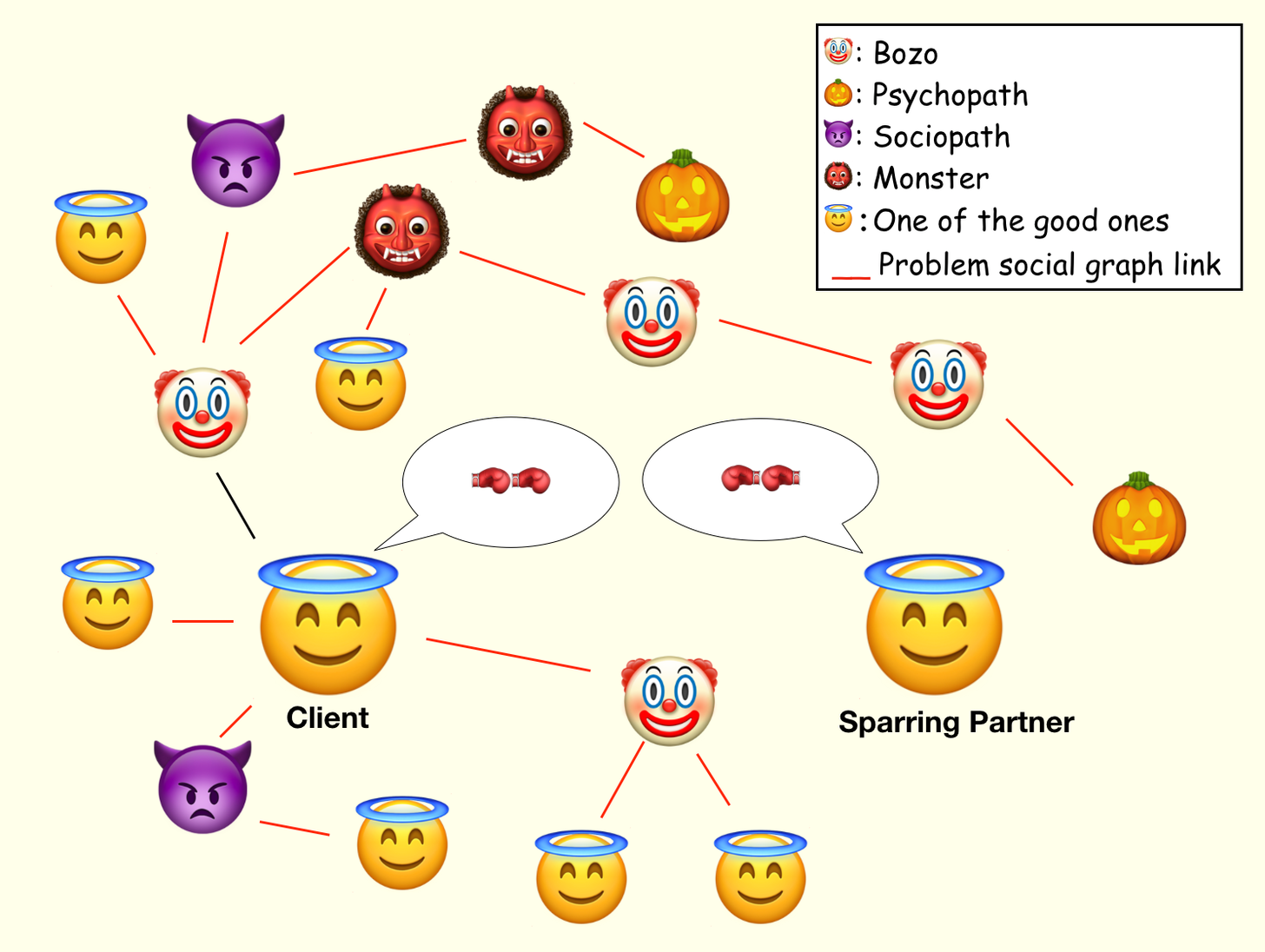

Here’s a picture.

The Central Dogma of Sparring

Here’s the core idea: in sparring the best starting assumption to adopt is I’m okay, you’re okay, they’re not so hot.

I’m going to call this the Central Dogma of Sparring.

The reference, for those of you unfamiliar with it, is the 1967 transactional analysis pop classic, I’m Ok, You’re Ok, which inspired a parody titled I’m Ok, You’re Not So Hot.

This starting assumption might seem unreasonably gloomy, and in fact goes against some very good management wisdom (Theory X vs. Theory Y for example, which suggests that the best assumption to make about others in an organization is that they’re actually competent and good by default).

The essence of the sparring assumption is that the client is not the problem, and neither are you, the sparring partner. The problem is other people.

This is not in general a good assumption to make about situations or organizations. So why is it a good assumption to make about sparring relationship setups?

-

First, they are seeking out a sparring partner because they have real problems they want to work through. It takes being fairly severely stymied for someone to seek out a sparring partner, so the problem is likely real.

-

Second, they are seeking out a sparring partner rather than a mentor, therapist, or functional/domain expert, which means they are preparing for conflict, which usually means they see specific other people as the problem rather than say a technical challenge or information ambiguity.

-

Third, though humans are of course prone to primary attribution error (blaming individual traits instead of situational factors for others’ behaviors), if you’re sparring with an experienced senior manager or executive, chances are they’re good judges of character, and experienced at sorting out people vs. situational factors. Otherwise they wouldn’t be where they are.

-

Fourth, though people in general tend to adopt lazy habits when it comes to psychology, convincing themselves that others are the problem so they don’t have to change, this is usually not as much of a factor with the sorts of ambitious people who end up as executives.

In my case, there is a fifth factor — as someone whose reputation was initially established on the basis of rather bleak writings about sociopathic office politics (many of my leads come from writings like The Gervais Principle, Be Slightly Evil, and Entrepreneurs are the New Labor) there is a further selection effect, where people seek me out specifically for those kinds of problems.

I suspect this generalizes too. Those who write with more positive frames are likely to attract engagements that are not structured as sparring engagements. So if you get into sparring at all, chances are there is a streak of pragmatic realpolitik in the way you present yourself to potential clients.

Early in my sparring practice, I was reluctant to accept the Central-Dogma-based starting frame that clients came to me with. I felt the urge to challenge them: what if YOU’RE the problem? What if it’s the system and these other people are basically good and competent? What if this isn’t zero-sum but win-win?

I learned the hard way that this is not a good idea for two reasons.

First: it’s a bad idea to challenge a client’s starter frame until there’s serious reason for doubt, or an obviously better frame is apparent. Unless the assumption that other people are the problem leads to bad contradictions and failures, take that initial diagnosis at face value and run with it.

Second: if people with other problems, requiring other approaches, are getting past your first-call filter, you’re not actually ready for sparring, and you’ll fail anyway. So challenging the Central Dogma is a way of second guessing your own gatekeeping gut-feelings.

In general, if the problem is not “other people” chances are you’ll be able to tell very quickly in the first exploratory call. In that case you should politely decline with a suggestion like “sounds like you need a therapist/life coach/executive coach/domain expert in X, not a sparring partner.”

In the first three cases, it is very unlikely that you can serve in those roles (they call for different personality types, as I’ve talked about before), and should therefore refer the person to someone else.

In the last case, domain expertise, you may want to accept, but then it’s not primarily a sparring engagement, it’s a mislabeled sparring engagement lead that just happens to match your domain expertise (such as general engineering, control theory, aerospace industry, or document/web technology in my case, which have all occasionally come in handy for me).

The Problem Social Graph

In any sort of engagement, not just sparring, you’re talking about, and through, problems. These problems involve the following variables:

-

The client

-

You

-

Other people (individually named, or local “types”)

-

The problem (like, “growth is flat” or “the new product is delayed” or “we need to design this new initiative”)

What makes it a sparring engagement is that you simplify the first two variables by assuming that neither you, nor the client, is part of the problem. If that assumption, based on the Central Dogma, turns out to be wrong, then the engagement should end as a sparring engagement, and likely not be handled by you.

This leaves the other two factors. How should you model them?

If you’re talking to younger people new to leadership roles, or middle management in larger companies, there’s a very good chance that the hard part is the problem itself, possibly because they haven’t encountered that kind of problem before, and you have, at least second-hand. These are the easiest sparring engagements: help them solve the problem-problem, and the people problems resolve themselves.

But if you’re talking to an experienced senior executive, the chances are quite low that the nominal problem is in fact the problem. The problem is nearly always other people. This means you have to model the people situation.

Enter the Problem Social Graph or PSG.

In this, you only include people who are relevant to the problem. And though you might find it a hostile starting default, you have to assume that everyone on the graph is part of the problem until proven not to be.

This is one reason in my Yakverse stories, many episodes are cast as detective mysteries involving the fictional Gig Crimes division, featuring Agents Jopp and Lestrode. Everybody is a suspect until proven innocent.

In my case, people sometimes come to me with one my own frames in mind (most often sociopaths, clueless, losers, which I developed in The Gervais Principle, though I have others), but usually they have their own archetypes as well. The cartoon above illustrates 4 common problem-social-graph archetypes — but these are by no means exhaustive:

-

Bozos (as in Steve Jobs’ “flipping the bozobit”) are fundamentally compromised by being clueless or otherwise being too disoriented to either work with or fix, and must be worked around.

-

Sociopaths (as in The Gervais Principle) are ambitious, politically sophisticated, manipulative people looking out for their own interests rather than the organization’s, and might not be interested in seeing the problems solved.

-

Psychopaths are messed-up people for whom work in the organization is just a convenient place to pursue dark impulses like sadism, sexual exploitation, and so forth (careful: often psychopaths present deceptively, as weaklings or passive-aggressive types).

-

Monsters are people explicitly but covertly pursuing agendas that are actively antithetical to the organization’s mission, such as fraud, industrial espionage, pure revenge motives aimed at specific people, and so on.

-

Good ones are people who show signs of being part of the solution. Often this has strong overlap with people the client likes, gets along with, and is allied with, but the actual definition is: people who already believe in whatever you and the client agree is the right answer to the problem.

Yes is a bleak set of archetypes with which to initially populate the problem social graph, but things are not quite as bleak as they might look.

Remember, you’re modeling a specific set of problems, not a healthy situation. You’re not modeling the organization as a whole, or its healthy but irrelevant parts. You’re leaving out people irrelevant to the problem — and quite often this leaves out a lot of the good people because good people usually find ways to do their jobs despite adverse environments. This means the only “good ones” left in the problem graph are ones who are trapped by the problem itself, unable to function effectively.

You’re isolating the problem subgraph of a larger social graph, and you’re starting with the assumption that you actually have a sense of the right answer to the problem.

Problem Graph Analysis is Not Tribal Analysis

That last point is something that is often missed by what I call the “tribal” school of management analysis. This is a school of thought that tends to ignore the content of the problem, and the situational potential for actual right and wrong answers.

The tribal school takes a “bothsides” approach to all tribes vying for control in a situation, and for better or worse, treats the problem as one of reconfiguring tribal boundaries, or using tribal conflict patterns to help their client win. Being right or wrong about actual problems is irrelevant in this frame. What matters is being more skilled at tribal warfare to ensure your solution prevails, regardless of whether it is the right solution or not.

Occasionally, this is the right approach in a sparring engagement, but that’s actually surprisingly rare. Usually, one of the tribes is actually right about the world, and what needs to be done, in a way that will only become apparent later. So a good filter criterion for accepting clients is whether they think they have a right answer to an interesting problem, or are merely trying to score a tribal victory.

So if you are interested in identifying and working with people who are right and helping them win by virtue of being right, you’re in problem-solving mode rather than tribal analysis mode.

This is not idealism, it is laziness. Being actually right about a problem is usually the biggest factor in being able to solve it easily, not power, executive sponsorship, resources, or tribal affiliations. It is odd that this needs to be said explicitly. The only company I know of that does so is Amazon: one of their leadership principles is “Good leaders are right, a lot.”

So while the setup above might look like it’s merely a fancy way of mapping out the in group/out group tribal boundaries relative to your client, and setting up a tribal analysis politics problem, it’s not. It’s about mapping out the problem boundaries on the social graph.

If you’ve picked the right sort of client to work with, their judgment of “good ones” is likely to be good, or at least consistent with your own definition of “good ones.” It is also likely to rest on an opinion about a set of right answers to problems rather than simple personal likes/dislikes. The ones labeled “good ones” on the graph, as I said, are the ones who believe in the right answer you and the client believe in.

So if there’s a tribal dynamic at work, you’re already part of it ideologically and it’s not a part of the problem per se. For example, I usually end up on the “product driven” tribe within a company rather than the “customer driven” tribe, and allied with technical people rather than sales or finance people. This is because I actually believe they are right more often, and should have more agency in organizations and run the show. This means my sparring practice is an ongoing test of my own beliefs about businesses and management, and a way of being scientific about any appreciative knowledge I bring to the party. As a sparring partner, I’m not neutral. I spar my management ideology, so to speak.

Second, problem graph roles are often already real, simply by virtue of being believed in by your client. The way your client is already dealing with the problem has trusted people they’re deploying as part of their current solution (you’ll almost never walk into a blank slate situation where something isn’t already being tried), and “problem” people they’re trying to fence out in one way or the other. This is a given part of the problem definition. Going against the grain of the problem social graph as it already exists is costly — so work with it unless you figure out that it is wrong.

In other words, the problem social graph is as much descriptive as normative, because it’s already become embodied in the situation by the time you walk in as a sparring partner.

This does not mean tribal analysis is useless. There are times when there is more than one way to be right. There are times when tribal dynamics themselves are the problem and there’s no separate objective problem. Solve the tribal problem and the other problems go away. For those situations, there is plenty of literature out there:

-

Art Kleiner, Who Really Matters

-

Dave Logan, Tribal Leadership

-

Seth Godin, Tribes

-

Bruce Bruno de Mesquita, Alastair Smith, The Dictator’s Handbook

Of these, the only one I actually recommend you read (though you should be familiar with all of them) is the last one, which is both brilliant and very useful when tribal analysis does apply as the proper framework.

But sparring is rarely about tribal conflict. Pure tribal problems tend to be both simple and boring. There is nothing interesting to be right or wrong about. Outcomes merely tell you who is favored by fortune; they don’t teach you something new and true about the world.

Solving pure tribal problems tends to be about simply making the right friends, the right enemies, buying off some people, cutting off other people, firing and hiring. Pure social boundary shaping. There’s surprisingly little to spar about. Either you have enough authority within the problem scope to reshape the tribal structure, or you don’t, and you have to either fall in with somebody else’s tribal agenda or leave the situation. Often, people call me after they’ve already figured out and solved the tribal part of the problem with a reorg or layoffs/hires, and are finally face-to-face with the actual problem.

What if after solving the tribal problem, there’s nothing else left to solve? That’s a pure tribal problem.

I’ll make a stronger assertion that I’m less confident about: if a problem becomes a pure tribal analysis problem, it’s generally not worth solving for intellectual interest, only for material rewards like money.

If the problem is a pure tribal problem, you’re very likely in some sort of Hobbesian endgame of market harvesting and extraction. There is no real vision or wealth-creation activity underway that makes problems interesting and worth solving.

A good sign is that sales or finance people dominate utterly (see my Yakverse story, Maneuvers vs. Melees). If you’re working with clients who are part of what I consider the creative, innovative side of the house — mainly engineering and marketing — chances are there are actual problems to be solved, that are worth solving, with right or wrong answers.

Sparring as Anti-Therapy

Let me close with one more remark on problem social graphs. In transactional analysis, the condition I’m okay, you’re okay is the foundation of healthy, game-free relationships that are rewarding to all parties within them.

This means sparring is a sort of anti-therapy, where you’re helping create broader positive effects from a healthy relationship between you and the client — two healthy people.

But there’s still a problem. It’s just not a therapy problem. And odds are (based on the priors that lead to sparring engagements) it’s a people problem created by some good people being right, and some problem people being wrong, about something real.

There may be tribal dynamics involved, but they’re not the main focus. The focus is figuring out the right answers, finding the people who believe in them, or can be persuaded to, and acting on them to solve problems, thereby learning whether you were actually right.

Helping the truth prevail, in short.

Of course this is an idealization. Of course, both you and your client have your share of psychological problems. Of course people you cast in various roles informally — bozos, sociopaths, psychopaths, monsters, good ones — are more than those reductive analytical labels you attach to them. Of course you might be wrong about your solutions to the problems.

But the starting point is preparing to act, by setting up a problem social graph, based on the belief that you’re right rather than wrong. Sounds tautological but it’s surprising how many people don’t get this.

This is a simple problem setup that will of course change as you think it through. Often, apparent “good ones” will be relabeled part-of-the-problem people. Less often, as you understand a situation, people initially tagged “problem people” might suddenly appear in a new light as part of the solution, or at least not relevant to the problem: red herrings.

These reconfigurations and relabelings are why it is not a tribal analysis problem. The graph changes as your understanding of the problem improves, with new facts becoming apparent. Behaviors presumed to be “bad” turn out to have harmless explanations, while other behaviors presumed to be “good” come to be seen as harmful. Working through this process like a detective solving a murder, gradually getting the right problem social graph converge with the right problem framing and solution, and acting on the answers you discover and learning whether they improve the situation or worsen it — that’s the essence of sparring.

This means success at sparring often amounts to setting up the initial problem social graph approximately correctly early, and refining it well as you progress. If you tend to get your initial setup very wrong very often, you’re not going to be effective as a sparring partner. Badly misreading a situation is not a good look for a sparring partner.

In other words, good sparring partners are right, a lot. Just like leaders at Amazon are expected to be. This is the test of the knowledge you bring to sparring. How do you get to where you’re right a lot? We’ll explore that later in the series.