Sorry for missing last week’s issue. Between an event I was hosting, a bit of travel to the Bay Area, and catching my second cold 🤧 of this awful cold-flu season, I just couldn’t get it out. I need to make up a proper posting schedule with a sick weeks/vacation weeks policy on my about page, like OG newsletter-er Ben Thompson does. I’ll do that soon.

The cold got me thinking about how fragile indie businesses are. Fragility is a better framework than precarity for us, since it focuses on internal structural things potentially within our control rather than external risks that are not (“precarity” has also become overloaded with political baggage lately, so I’m going to avoid the term).

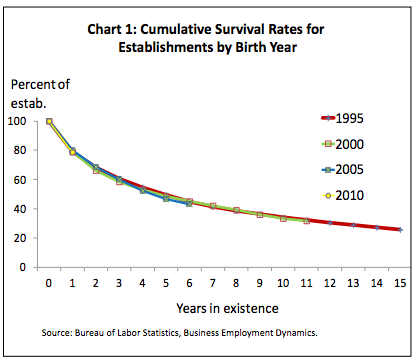

I can’t find statistics for the gig economy, but we’re all effectively small businesses, so I’d expect trends to be similar to small businesses in general. Here’s a chart from the US Small Business Administration for the American case. I expect most of the developed world presents a similar picture. Only about 50% of small businesses survive past the 5th year. At my 9 year point, the survival rate is 40%, so 3 out of 5 people who went indie the same year I did are now out of the game.

I suspect this picture looks far rosier than it actually is. I once met a guy at an airport who specialized in franchise-startup consulting, helping aspiring small business owners choose and set up chain franchise restaurants. He claimed that the survival rate for franchise operators past 5 years was like 70%, but for non-franchise restaurants it was less than 10%. I haven’t verified that, but it sounds roughly right and matches anecdotal evidence I’ve encountered elsewhere. So small businesses that are effectively part of ecosystems underwritten by larger businesses borrow some robustness from their mother ships, but give up some margin and equity appreciation potential in return.

On the other hand, fragility questions always remind me of Kongō Gumi, which was, for a long time, the oldest continuously running business in the world. It was a small Japanese family firm specializing in Buddhist temple construction. Founded in 578 AD, it finally shut down in 2006, succumbing to very banal financial hardships of the sort any business might succumb to. It was acquired by a larger company (I doubt the terms were good, or commensurate with the brand equity of 1442 years of operation — distressed businesses are generally sold for pennies on the dollar).

Point being, it did not take a Godzilla attack to end the long game for this 1442-year-old mom-and-pop shop. Just some routine errors that would be recoverable for businesses in good shape.

Both the SBA actuarial statistics and the peculiar longevity and tame ending of exceptions like Kongō Gumi invite analysis. Is the latter an existence proof of an antifragility strategy available to us one-person bands that we might discover by digging into such cases? Or is it a fooled-by-randomness effect, with examples like Kongō Gumi merely being exceptions that prove the general rule that small businesses are fragile?

Fragility and Scale

I personally think the longevity of Kongō Gumi was pure luck. A random data point from an unusually stable business sector in an unusually stable and conservative country. I doubt we could construct a real playbook for business longevity by looking into its history. If somebody wants to try and prove me wrong by actually researching the case, and similar cases (here’s a list of oldest companies), I’ll be happy to post your findings here as a guest issue.

First-principles analysis would suggest that in general, the smaller a business, the more fragile it is likely to be. And nothing is more fragile than a one-person business operating in the gig economy.

A simple bout of the flu can be as devastating for a gigworker as a hurricane for a larger business. I think I have enough earned trust that I wouldn’t expect a lot of you to unsubscribe if I had to take a week or two off due to illness. But what about 3 months? Or 6? Or a year?

I don’t think your goodwill and concern for my health or financial wellbeing would extend that far. Beyond a point, I’d have to shut the newsletter down and find replace the income with an alternative source that can weather extended illness.

The fragility on the consulting side is even more drastic. One of the things I worry about is: what if I land a big, time-bound gig of say 3 months that I expect to pay my bills for 6 months, but then something like a parental health emergency forces me to go be in India for a month, unable to work on the gig? A paycheck employer would likely be understanding and work with me to figure out a revised schedule of work deliverables, or take unpaid/partial salary time off. A consulting client? I’d expect the gig, especially with a new client, to either evaporate, or go to someone else.

These are harsh risks that you must not be in denial about if you are in the gig economy, even if you don’t have good solutions to managing them. I certainly don’t have answers. But that’s not a good reason to sweep the questions under the rug.

This is something I try to be conscious of as I write this newsletter. Having been in the game for 9 years, there are certainly some things I understand better than those of you with less experience, and certain risks and challenges I navigate better. But there’s a vast universe of uncertainties and risks I understand no better than any of you. My only advantage on those fronts might be not being in denial about their existence.

I’ve had enough near-misses to lose any false sense of security I might have developed in the wake of the first flush of self-confidence from landing my first couple of gigs.

Small is Fraught

Many lines of business that indies like getting into do not allow for easy scheduling of breaks, interruptions of service, or service-level degradations. “Passive income” is mostly a myth.

Though you are only a single human, you are seen as a business, and people expect the kind of reliability and stability they expect of bigger businesses with far greater redundancy in capabilities. This often means indie businesses put themselves under enormous pressure (and take on the resulting health stress) to deliver to expectations set by bigger businesses. That’s why you hear of hard-working small business owners, in sectors like cheap restaurants or convenience stores, who haven’t taken a day off in years, let alone a vacation. They work to a 24-7-365 SLA, and don’t have the staffing redundancy to cover for their personal absence.

At the other end of the load-factor spectrum, there is the kind of spiky gig work where you can make enough in a month or two to pay for an entire year. But then you don’t have strong control over the timing of the spike. If the opportunity spike coincides with an emergency spike, you get hit with a double jeopardy: you lose the income opportunity, and you have to deal with the emergency related expenses. It’s what Charles Perrow labeled a normal accident — a condition in a complex system (like nuclear reactors or the modern gig economy tech stack) where two unrelated and ordinary risk events coincide to create extraordinary risk conditions.

This risk was driven home for me last year, when my father-in-law fell seriously ill and passed away in August. His passing demanded both time (more from my wife than me) and significant expense, over several months. At the time, I had just started my year-long fellowship with a predictable income, and had decent reserves and inbound invoice payments, so we were able to weather the incident relatively gracefully in financial terms. But I couldn’t help but run the counterfactual in my head: what if this had happened when I’d been in a cash-flow slump with low reserves and no invoices due, and no longer gigs on the horizon? Or worse, on the cusp of a major spike-income gig that I might have had to turn down? It might have been enough to knock me out of the game, drain all my reservers, drive me into long-term credit-card debt, and force me to look for a paycheck job on an emergency basis.

This is not a theoretical scenario. I’ve come close to that condition 3-4 times in the last 9 years, but fortunately never actually had to drop out. But my wife and I still have three elderly living parents between us, plus all the usual risks everybody faces: illness, disability, catastrophic losses, and so forth. And insurance can only play a limited role in managing this risk. Much of the risk mitigation has to come from cash flow management and savings/investment habits.

The line between continued survival in the gig economy and crashing out of it is a very thin one, no matter how long you’ve been in the game. Don’t get complacent about either the risks, or why the risks are worth taking on (short answer: freedom).

Antifragile Gigwork

Can small businesses and gig economy careers be made antifragile by clever design? There’s some evidence that there’s some room for that. Research out of Royal Dutch/Shell that led to a book called The Living Company by Arie de Gues suggests that there are two factors (ht Mick Costigan and Peter Schwarz at Salesforce for ELI5ing the findings to me) driving company longevity.

-

One of those factors is an open, experimental culture. Nice. You and I, brave exploratory adventurers of the gig economy, we’ve got that covered.

-

The other factor, unfortunately, is simply levels of reserve resources. Financial conservatism in short. Yikes.

Unfortunately, I think the second factor is by far more important for smaller businesses, and almost the whole factor for indies.

This finding jibes with the observation, in Bill Janeway’s book on the startup economy, Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy, that what gets startups through turbulent times is simply cash and control. Cash reserves (raise more funding than you need if you expect a downturn, and hold on to it) and control (keep control of your company/board) is startup survival 101.

I think we can reasonably extrapolate such findings to the gig economy, with extreme added prejudice. These ideas apply much more strongly to us, since our incomes are usually based neither on securitizable assets like restaurants, nor on VC-investible activities like startups. We generally do not have access to OPM (Other People’s Money) even for things paycheck people take for granted, like home-buying. This picture is changing. Now that I’ve been in the game long enough, I routinely get working capital loan offers from services like Paypal and Stripe (as well as scammy offers via shady phone calls). But it’s very limited kind of access to OPM, and definitely not cheap capital. More importantly, I don’t feel comfortable taking on that kind of OPM debt without a more capital-building type plan to generate a higher return rate than the interest rate. And most of us in the gig economy aren’t building up capital assets, only goodwill and reputation. If we were, we’d be startups.

The question is, can we do anything about these operating conditions, or are we doomed to be the canaries in the coal mine of the economy at large, the first to get slaughtered by bad times?

Are You a Lindy Indie?

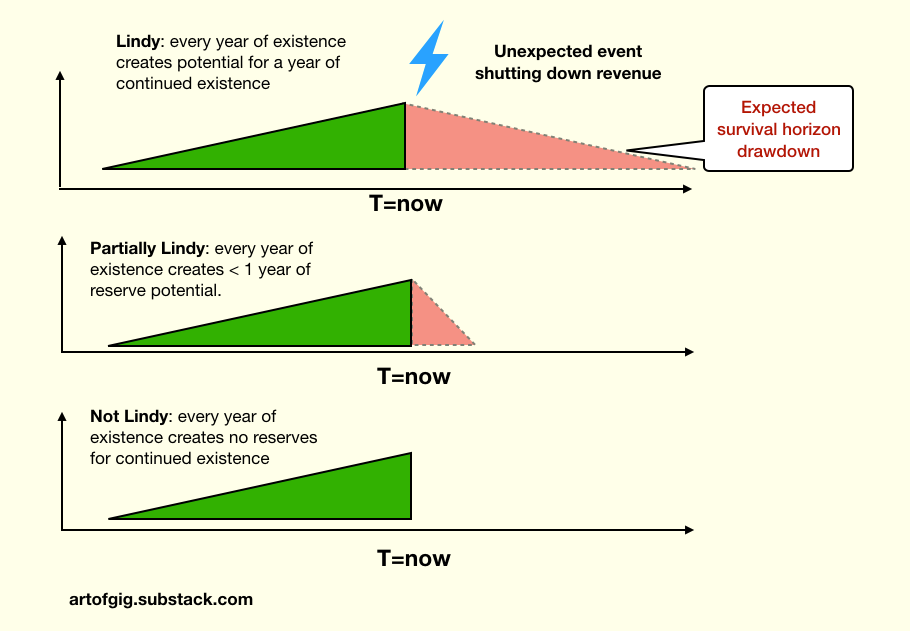

Nassim Taleb popularized a good lens on fragility: the Lindy effect. Applied to our problem, the idea is, if a thing has survived for N years, you should expect it to survive for another N years. So I’ve been surviving in the gig economy since March 2011, and if my hustle is Lindy, you should expect to be in business till March 2029 right now.

The Lindy effect is something of a blackbox model though. You can’t just assume it holds. You have to open up the box and figure out if, how, and why. Then, perhaps, you can pose “Lindy” as a design challenge to solve for.

If you accept the openness+reserves model I referenced, and approximate survivability as just a function of reserves, Lindyness is really just a kind of 1:1 ratio between expenses run rate and reserves accumulation run rate. A very simplistic model looks something like this:

The reserves might be in many forms: liquid cash and cash-equivalents. Assets like home equity you could use for securitized debt. Accounts receivable. Relatively low-maintenance income streams like ebook sales that won’t turn off overnight if you stop maintaining them.

But whatever form they take, being a Lindy Indie really just boils down to building up reserves. Far more reserves than paycheck economy types build, because we in the gig economy typically lack the risk underwriting benefits of being tethered to a larger, less fragile entity.

This goes beyond just structural effects like employment itself, to things like having a strong community of friends and colleagues who might pitch in and help you when you’re in trouble. For most working adults, a significant fraction of their social capital is also tied to being in a job.

Indies have to make do with a much smaller social safety net of close friends and family they can call on.

So where does that leave us? If we want to be Lindy Indies, we kinda have to design Lindyness into our businesses ourselves. The brute force answer is to simply cut down expenses till they are half the after-tax income, saving the other half in conservative reserve form (cash).

This is a shitty answer, and basically impossible for most of us.

Are there better answers? I’m going to explore the question in future newsletter issues.