For people in paycheck careers, the “career path” is a familiar and useful long-term planning artifact. For free agents on the other hand, there is no such convenient construct, which makes meaningful long-term comparisons between paycheck and free-agent careers hard.

Worse, the lack of such a construct means free agents often fail to even imagine meaningful progression in the work lives, leading to increasing disenchantment through lack of growth.

So they do the same thing in Year 10 as they did in Year 1, not because they want to (which is a fine thing), but because they can’t imagine alternatives. Often, they end up rationalizing this lack of imagination (a bad thing) as lack of ambition (which can be piously spun as a holier-than-thou “good thing,” as in quitting the rat race and feeling superior to paycheck types).

We need a meaningful way to talk about long-term career planning for free agents, a way that allows for apples-to-apples comparisons with paycheck careers. And obviously we can’t use variables specific to paycheck jobs, like “title”, “budget” or “number of reports,” OR variables specific to free agents, such as “number of clients” or “bill rate.”

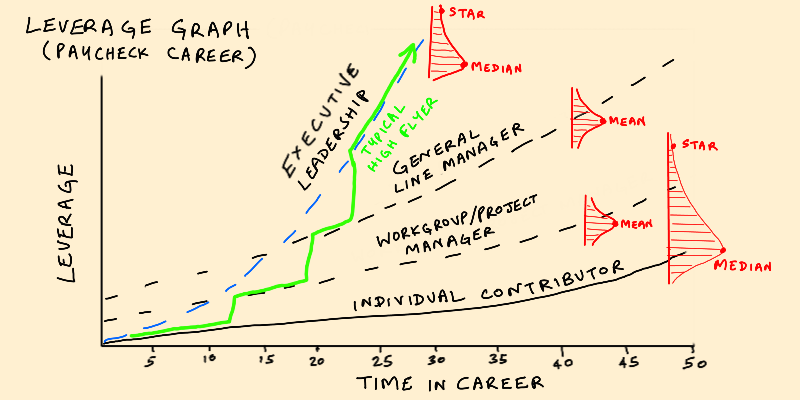

I made up a construct that I think works — a leverage graph. It is based on the observation that the unifying feature of both free-agent and paycheck careers is that if you do well, you land in situations with increasing leverage, via relatively discontinuous jumps. These jumps are promotions in paycheck careers, and new types of gigs in free-agent careers.

Let’s understand the concept in paycheck career terms first, since it is the more familiar and legible case. Here is the leverage graph (green line) for a typical high-flyer paycheck career:

I’ve left the term leverage undefined, but it is loosely anything that shapes the actions of the company beyond your individual work output. So individual contributors might produce something that is used by others in the company. Managers raise or lower the productivity of everyone under them based on how good or bad they are. Leverage is closely related to knowledge. The more you know and understand, the more you can consciously engage in leveraged behaviors with bigger consequences. Leverage is how knowledge turns into power over the organization’s fate. So a leverage curve is a big brother of a learning curve.

Here’s how you read this graph:

-

Each smooth curve is a learning curve with a single leverage type; the jumpy green curve is a leverage curve for an individual career that jumps across leverage types.

-

This diagram illustrates successful career paths with at least a little lifelong learning, but obviously people can and do “plateau” on a long S-curve or crash

-

Each smooth curve has slowly compounding gains over a single-leverage-type career; higher curves have faster rates of compounding leverage

-

The default curve is the solid line (individual contributor); you can stay on so long as you maintain a minimum acceptable performance for your experience level

-

The managerial curves (black dashed) are not default, but not exceptional either. There are systematic ways to get on them and stay on them.

-

The executive leadership curve (blue dashed) is exceptional, and crosses the other three. There is no systematic way to get on it or stay on it; you have to hack your way onto it.

-

There is a leverage distribution on each point of each curve. Not everybody on the same nominal smooth curve with the same years of experience has the same leverage.

-

Managerial curves feature normal leverage distributions at every point. Exceptionally good and exceptionally bad performers both tend to be weeded out.

-

Individual contributors and executives have non-normal leverage distributions. While exceptionally bad performers tend to be weeded out as on the managerial paths, exceptional stars (“10x” types) can persist and grow in their roles.

-

True promotions are leverage-increasing jumps across curves, and to be distinguished from grade-progression promotions within each curve.

Leverage in Paycheck Careers

The leverage graph should be familiar and easy to parse for people with some work experience, but here’s an illustration.

For engineers, for example, there are generally two recognized career paths in big companies. The first is a path as an individual contributor rising from an entry-level role to one with a title like “Principal Engineer” or “Fellow,” marking deep expertise in some area. The progression is often marked by a system of grades, such as 1-10. At Google, for instance, the two star celebrity engineers, Jeff Dean and Sanjay Ghemawat, are the only “Level 11” engineers among thousands at the company.

This path can play out across multiple companies within an industry that share a technological base.

The second path is a technical manager path, where you rise from individual contributor to some sort of general line management role, via an intermediate role in project or workgroup management. The difference between the two is whether you manage other managers, or whether you manage individual contributors (a crucial distinction that is central to management theory, but not critical for free agents to understand deeply unless you consult on organizational psychology problems). This path typically tops out at some level that is internally recognized as just short of an executive (aka business-risk-owning) role, such as an “Associate Vice President” or “Director.” The titles don’t matter. What matters is that leverage increases across and within curves.

Leverage (and compensation) can continue to increase after the company runs out of titles and grades to hand out.

Along either path, exceptional people tend to get picked out and groomed for executive leadership, but unlike progression through individual or managerial grades, the process is not systematic.

Engineers who rise to executive roles typically do so by showing a capacity for risk-taking leadership early in their careers, pulling off high-stakes projects that others didn’t think possible. This marks them for fast-track grooming for leadership, customized roles, and customized compensation packages. “Executive” roles typically begin with VP titles, but again, don’t take titles too seriously. It’s the substance of the role that matters — participation in the risk-taking of the business being central to the job.

The career paths in other functions such as sales and marketing are similar. Career paths in what are known as “staff” functions like HR are somewhat different, in ways that make this leverage graph view less useful.

Leverage in Free-Agent Careers

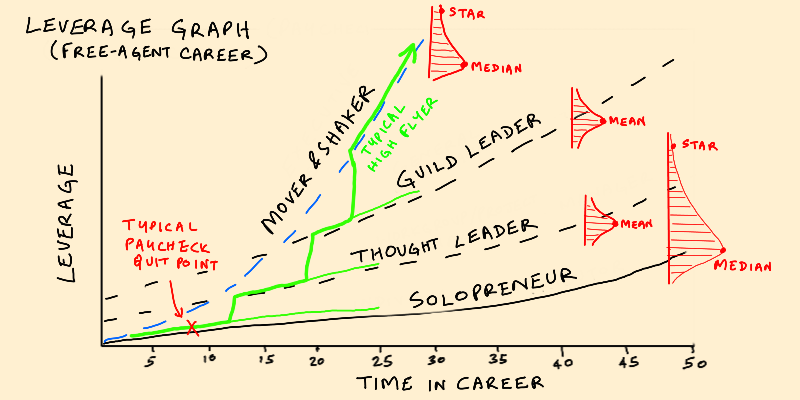

Now that we have the familiar paycheck career case established for reference within this leverage graph framework, this version for free agents should be easy to read.

Since most people bank a few years paycheck work experience before embarking on free-agent careers, the story begins at a non-zero quit point on the x axis. This is anecdotally around 5-10 years, though it is rapidly falling, and many younger free agents are skipping a paycheck world bootcamp altogether, either out of choice or necessity (which has consequences good and bad — they lack traditional organizational literacy, but also have fewer bad habits of thought to unlearn).

The big difference between the paycheck and free-agent versions is the nature of the leverage represented by the y axis. For paycheck types, it is budgets, number of reports rolling up to them, and participation level in strategic decisions. For free agents, it is informal influence in their economic sector. This difference leads to a particular portrait of the four smooth leverage curves a free agent must navigate:

-

The solopreneur is the equivalent of the life-long individual contributor, who slowly gets exceptionally good and increasingly unique at something. Their leverage lies in being the loci of accumulation for industry-wide best practice knowledge.

-

The thought leader is someone whose work directly influences the work and choices of others. As the derogatory jokes suggest, this is the equivalent of your basic project or workgroup manager within the corporation. The thought leader is the pointy-haired boss of the gig economy. Their influence is exercised in a diffuse way through public writing and speaking, and the production of artifacts (such as open-source programs or influential terminology) used by others. Their leverage lies in being the trusted loci of consensus formation around key trends, standards, and evolutionary choices in an industry.

-

The guild leader is someone who begins to take on something of a market-making role within the gig economy, helping people find gigs, making key backroom connections, and doing a degree of event organizing and community building. To the extent there is a need and opportunity for any sort of collective action, they catalyze it. Note though, that the incentives are wrong for them to play union-leader type roles, because the gig economy, especially above the API, is fundamentally an economy of unrepentant scabs who side with capital by default. The collective action takes other forms. Their leverage lies in being loci of network capital accumulation.

-

The mover and shaker is someone who can genuinely influence the course of events in an industry through the force of their personal reputation alone. An example is Linus Torvalds. He can shape the vast universe of Linux with his personal opinions, and exercise influence at a level similar to the CEOs of big tech companies. Their leverage lies in being the loci of extra-institutional agency based on connections to ground reality unmediated by large organizations.

Besides this big difference in sources of leverage, the free-agent leverage graph also has one other key difference: In the paycheck leverage graph, typically the curves are mutually exclusive. Managers rarely continue to do individual contribution work. Executives rarely spend a lot of time directly managing.

In the free-agent version though, this is not true. As I’ve illustrated with the forking green path, you often have to keep doing the work of the lower level curves even as you take on work on the upper levels. This means, at any given time, you’re exercising many different kinds of leverage simultaneously. Often this happens across the multiple gigs you might be doing at any given time.

For example, let’s say you’re doing 4 gigs at once:

-

In Gig 1, a solopreneur gig, which you got based on your paycheck resume, you’re applying a technical skill that the client lacks internally but is common in the industry.

-

In Gig 2, a thought leader gig, which you got via a viral blog post, you’re applying models and ideas unique to you to a specific challenge faced by the client, perhaps by delivering a workshop.

-

In Gig 3, a guild leader type gig, you’re helping a young startup new to a market map the environment, navigate crucial meetings, hire talent, and structure external relationships.

-

In Gig 4, a mover-and-shaker type gig, you’re sparring with a well-known executive, helping them make decisions that you know will set precedents for the industry and make the news.

Depending on the percent of time you’re devoting to each of these, and the amount of money you’re making from each, your role in the gig economy is some sort of superposition of the four curves. While people in paycheck roles do sometimes spread themselves out this way across projects, typically, they tend to play the same kind of role in every project.

So now that you have a construct for thinking about your career as a free agent, the question you have to ask yourself is: where are you, where are you headed, and where do you want to be headed?