We talk a lot about 4 types of economic entities in this newsletter: big organizations, startups, under-the-API gig workers (such as rideshare drivers), and finally our core class — independent consultants. The superficial structural differences are obvious, but what are the real, deep differences that account for their different economic roles and mutual relationships? I’m going to try and explain it with 2 pictures.

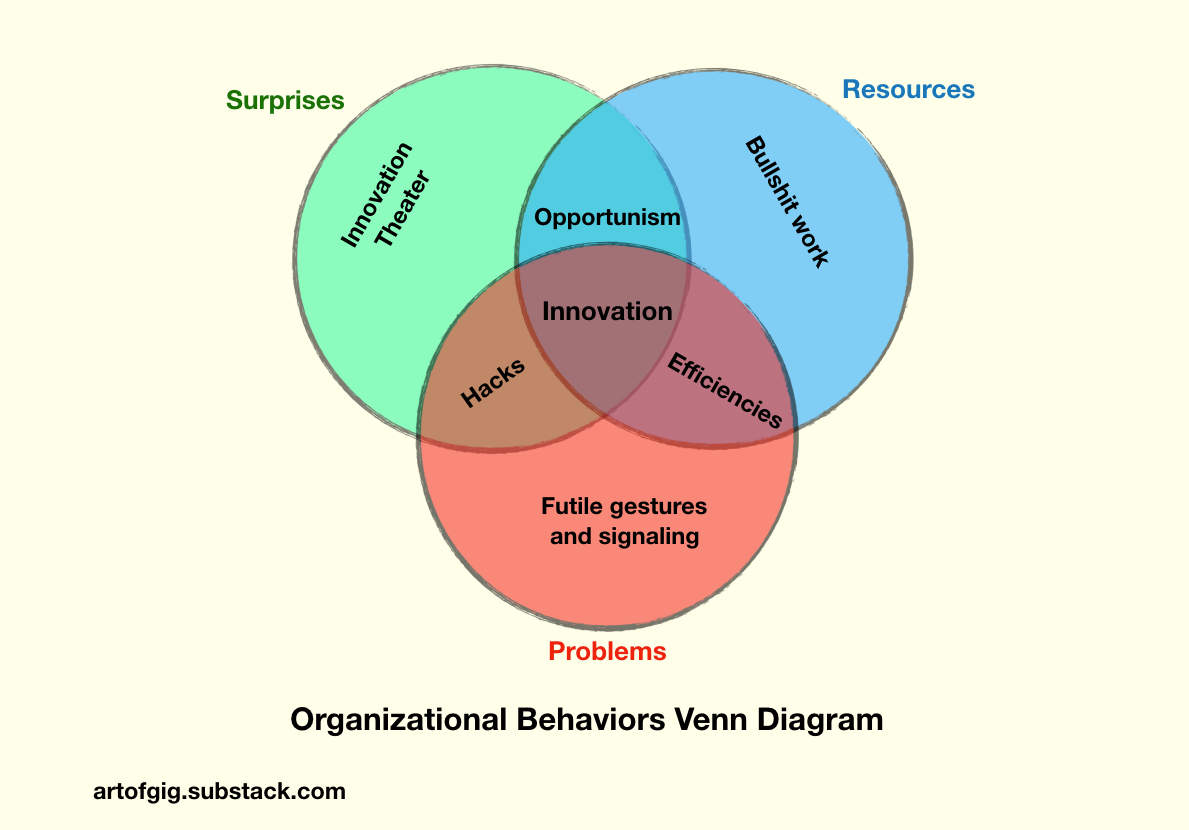

The first picture is a generic Venn diagram of organizational behavior modes that applies to all 4 (considering free agents to be 1-person organizations). All organizational behavior can be understood in terms of the intersections of problems, resources, and surprises, which intersect to create 7 behavioral zones like so.

I’ll let you think about my 7 behavioral zones on your own, but I want to make a couple of general comments before zooming in on the indie consulting version.

The first thing to recognize about this diagram is that problems and resources don’t have to match/overlap much, but do need to be approximately equal in magnitude, which allows for solving them via creative trade and commerce. Bullshit work usually indicates underutilized capacities that can be sold to others. Futile gestures and signaling generally indicates real problems that could be solved by third parties. If the scope of opportunities to spend/make money are well matched, there is the possibility of increasing the efficiency zone.

But if your problems sum to $1 billion and your resources sum to $100k, there’s a basic mismatch that cannot be solved without some true innovation and probably brute-force capitalization. More likely, you will simply try to shrink the scope of the problems you accept to match the resources you have, or die trying.

The second thing to recognize is the role surprises play in shaping organizational behavior. Good/bad doesn’t matter. Sometimes unexpected gifts turn out to be curses. Other times, making lemonade from lemons turns out to be a huge win. What matters is that something unexpected has entered your world from the vast unknown outside.

I’m something of an extremist on this point. I believe nothing truly significant ever changes in an organization without the injection of a surprise from the external world, followed by a creative and imaginative internal response to it. Surprises are necessary (but not sufficient) fuel for growth and change.

Without a stream of external surprises in the picture, the problems-resources relationship is generally in a zero-sum gridlock and doesn’t offer much opportunity to break out of bad situations. All you can hope for is slow, painstaking growth or decline driven by conscious discipline.

But external surprises can break the gridlock. Whether in positive or negative ways is partly, but not entirely, up to you. Organizations differ in their “surprisal surface area”, both in terms of the scope of generally salient surprises, and the degree of direct overlap between the stream of surprises and the resource/problem gridlock picture.

Varieties of Surprisability

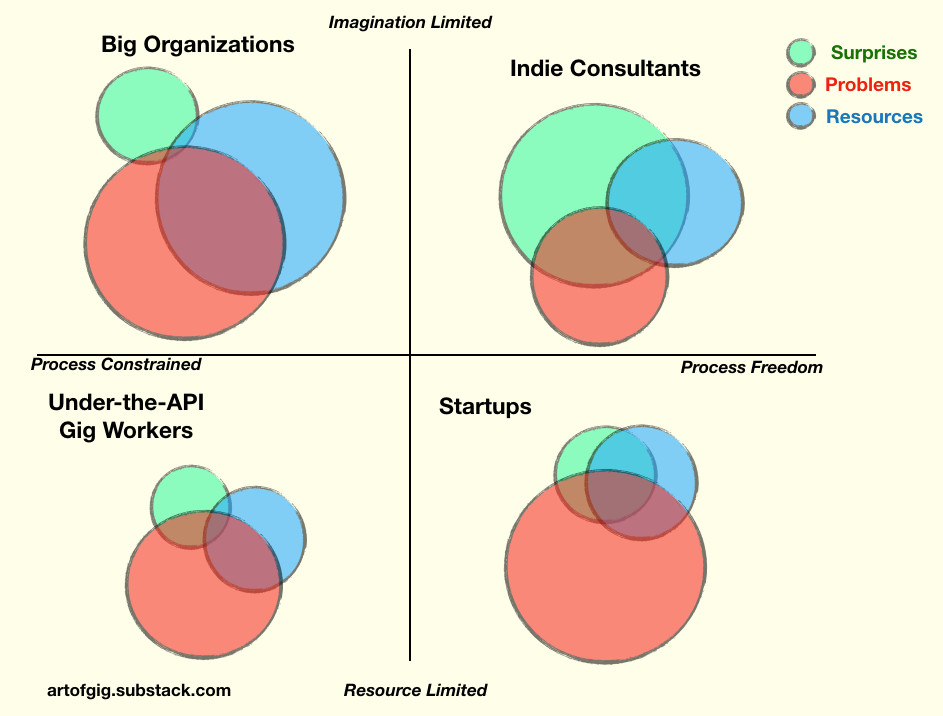

The trick to understanding different types of organizations is recognizing that these circles and intersection zones are sized differently for our 4 basic types. And of course we can plot them on a 2×2 😎. What I’ve plotted here are typical representatives of each class.

See what’s going on here?

Big organizations and under-the-API gig workers are both process constrained. This means relatively low scope of relevant surprises (small green circle), and weak ability to respond to them (small overlap zone).

Startups and under-the-API gig workers are both resource limited, which means there is a significant mismatch between the scale of problems they have to take on and the resources they have available to address them (red circle bigger than blue circle). This means the situation is unsustainable long term without some differential growth or shrinkage to balance the two. Startups and gig workers are both in grow-or-die mode, and the growth is required as much to right-shape their economic roles as to make them profitable.

But indie consultants are unique among the four types in having a much bigger surprisal surface area, and overlap zones, than the other three. Because we are neither process constrained like under-the-API gig workers, nor faced with a severe mismatch between resources and problems like startups. So we have a very significant openness to surprisal, and a much higher ability to solve problems in ways besides arguing over resources with others.

The Art of Being Surprisable

A trivial example: if you’re reasonably smart and broadly curious and interested in stuff, almost any item in the news can be fodder for something like a blog post, or quick-turnaround expertise acquisition if you want to invest more time.

These can then be turned into money fairly easily, with mechanisms ranging from subscription newsletters to online classes, to corporate workshops, and spec work for appropriately targeted clients. This means you can respond to a LOT more of what’s going on in the world than the other 3 types of organizations. This is the reason the main product a lot of indie consultants sell is surprises transformed into customized/personalized action optionality for clients. Because we have surplus capacity to respond to surprises ourselves, we sell that capacity to others who have a deficit, due to reasons of either process limitation, or resource limitation, or both.

Startups are equally process-unconstrained, but their capacity for surprisal is limited by the fact that they are trying to build out one very specific ambitious thing with very scarce resources, so their green circle of relevant surprises is smaller. Otoh, big companies have a lot of resources, but too constrained by their processes to ingest significant surprisal. Under-the-API gig workers of course, are the most constrained of all.

You need 5 things going on to turn surprisability into economic leverage:

-

Openness to experience: You have to be paying attention outside your focal zones, and ideally, actively provoking parts of the environment to generate surprise-fuel for yourself.

-

Depth of curiosity: A surprise by itself is like rain. Without adequate forest cover or porous soil, it just rolls off like a flash flood. To “trap” surprise in the form of an asset, you need a rich and broad awareness of the world, so you can integrate surprising things to things you already know/do in interesting ways.

-

Lack of missionary lock: Your life should NOT be built around a single overarching mission to the degree that you can’t opportunistically in ways unrelated to other things you are doing. If you have that kind of lock, you need to turn yourself into a startup.

-

Imagination: Ability to see the possibilities latent in a surprise that are within your zone of actionability. Nobody else can do this for you. This is a kind of connecting of dots that relies on your private knowledge.

-

Boldness: The ability to overcome doubts and just act to be the agent of whatever the environment has enabled to happen. The ability to say: this connection is just waiting to be made, somebody has to make it, why not me?

That’s ODLIB if you like mnemonics: Openness to experience, Depth of curiosity, Lack of missionary lock, Imagination, Boldness.

If you think your surprisability is weak, you might want to start a “surprise log” in a notebook, or even as an evolving thread of tweets. Sensitizing yourself to surprise is not hard. Be careful not to turn it into an “idea log” though. It’s important to learn to see the surprise itself, and the potential it opens up, and not jump too quickly to a way to do something with it (and most of the time you won’t be able to). That’s the only way you’ll train your surprisability.

Pro-tip: a surprise doesn’t have to be a new development or seem obviously surprising at first glance. It just has to be newly surprising to you, via an insight. It can even be something that didn’t happen (“the dog that didn’t bark”). A surprise stream is not a news feed.