It’s newbie-consultant vaccination week here at the Art of Gig (and booster-shot week for the experienced ones who may have learned and forgotten the lesson I want to talk about). The vaccine comes in the form of this triangle, and is meant to protect you from an operational hazard of indie consulting: charges of parasitism.

More specifically, the vaccine is meant to protect your psyche against the constant gaslighting and broad-strokes scapegoating of consultants by other kinds of economic actors, making you doubt your own economic worth relative to theirs, and wonder whether perhaps you are in fact morally inferior to them, as they insidiously keep suggesting, with their holier-than-thou sermonizing.

It’s particularly worthwhile getting your immune defenses strengthened right now, since McKinsey’s sketchy practices, which I did some commentary on last week, remain in the news cycle with the story about their work with the City of New York to reduce violence at Rikers (tldr: it seems they failed and violence actually increased). And reports like this paywalled article titled How to Avoid the Startup Trap of the Parasitic Consultant (I only read the lede).

Parasitic Competition

The gaslighting and scapegoating of consultants is most likely to be led by two species of parasite that compete with parasitic consultants (who do exist) to feed on weak organizations: charismatic but weak leaders, and unaccountable bureaucrats.

To vaccinate yourself, you must learn to identify and counter the trash-talk from these two wonders of organizational ecosystems. You must learn to firmly defend your worth, especially to yourself. And even go on the offensive in internal battles if necessary, if you believe you are being unfairly maligned as a parasite, when you are in fact a Good Gigster fighting the Good Fight against the actual parasites.

Here’s the basic dynamic you have to understand.

As organizations weaken, all three species in their non-parasitic forms become subject to the morally hazardous incentives that lead to parasitic behaviors.

Usually two of the species will appear together, and act to lock out the third, making it a two-way duel. And sometimes, only one of these species will appear, and cut off the other two.

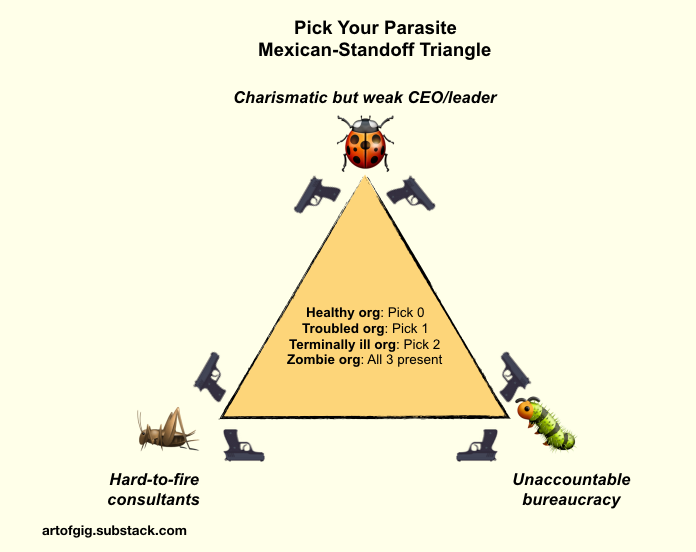

But in seriously weakened organizations, all three are often present, leading to a sort of Mexican standoff among them, with shifting alliances as the situation unfolds. This is the situation I’ve illustrated above in the cartoon (the locust, ladybug, and caterpillar in the diagram above are pests rather than parasites, but oh well, you get the point).

Consultants, as outsiders with no locus standi in the official narrative, and biased towards public silence by both long-term business model considerations and contractual obligations, are naturally vulnerable to being blamed for the effects of parasitism, whether or not they are actually being parasitic in a particular case.

Basically, because you don’t want to gain a reputation for throwing your clients under the bus under stress, and because non-disclosure and non-disparagement clauses probably make it legally risky to do so anyway, you are easy and safe to blame. Perversely, this can make angry consultants, who feel unfairly maligned, turn parasitic even if they weren’t previously. The tempting line of reasoning goes: might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb, and get yours while the getting is good.

Charismatic-and-weak leaders and unaccountable bureaucrats aren’t the only ones who like to preach anti-consultant sermons, and score cheap points by tarring our noble trade with a broad brush. But they are the ones who matter, because they are in a position to affect the roles consultants might be playing, and also know enough to be effectively disingenuous in their anti-consultant sermonizing.

Others who join in, especially in the media, tend to have no idea what they’re talking about. Their unaided criticism (sincere or disingenuous) tends to be so wide off the mark, it does little to no damage. But competing parasites can sometimes co-opt these less effective critics and target their outrage to be more effective.

In the ongoing McKinsey saga for instance, while clearly McKinsey is guilty of a degree of parasitism, it is equally clear that weak leaders and unaccountable bureaucrats are throwing McKinsey under the bus. The media reporting on this either isn’t well-versed enough in these dynamics to see what’s going on, or they do, but are playing along because they think McKinsey is worth throwing under the bus anyway, and an easy target, even if the other two species of parasites are possibly more to blame.

Assuming you’re among the good players who aren’t actually being parasitic in your gigwork (if you’re subscribed to this list, I think it’s a fair assumption, hence the headline), vulnerability to undeserved charges of parasitism creates two problems for indie consultants in particular.

The easier problem is making yourself practically immune to accusations of parasitism and structurally distancing yourself from actually parasitic consultants.

The harder problem, and the one the triangle vaccine is meant to address, is hardening your psyche against the gaslighting, making you philosophically immune to it.

Let’s tackle the harder problem first, because it will make the easy problem even easier.

Philosophical Immunization

The key to philosophical immunity is to firmly call bullshit on the holier-than-thou moral posturing that usually lies behind accusations of consultant parasitism. The key to this is understanding who feels threatened by the presence of consultants (whether honest or actually parasitic), when, and why.

Organizations are vulnerable to three kinds of parasites when they are in poor health.

-

Charismatic but weak CEOs/leaders who function by creating strong reality distortion fields around gaps in their weak leadership. They are vulnerable to their reality distortion fields being punctured by skeptical, informed scrutiny. Think the WeWork CEO Adam Neumann, or Theranos’ Elizabeth Holmes.

-

Unaccountable bureaucracies that quietly control the organization from the inside and are vulnerable to their internal monitoring and inspection processes being revealed as ceremonial shams protecting inefficiency, ineffectiveness, incompetence, or profiteering by skeptical, informed scrutiny. Think the career leadership at the government agencies involved in the McKinsey cases. Or most old-economy big companies.

-

Hard-to-fire consultants who get their hooks into organizations, and make themselves indispensable to the day-to-day-functioning once they are in. They are vulnerable to their work being exposed as self-serving and against the interests of the organization by skeptical, informed scrutiny. Think McKinsey.

For each of these bad-actor species, the other two kinds of bad actors represent competition in the feeding frenzy, but the bigger threat is good-actor types at the other two vertices because they are the ones who can direct the skeptical informed scrutiny at them, and lead efforts to resist and reverse the parasitized organizational condition:

-

Strong effective CEOs who don’t need to distort reality to cover up weaknesses in order to either lead the organization or profit personally.

-

Professional, high-integrity bureaucracies whose processes can pass internal or external scrutiny with flying colors.

-

Good consultants who can cast an unflattering light on internal realities and self-congratulatory narratives through pointed, detailed, and specific external comparisons.

Notably, Steve Jobs (though he had his share of weaknesses) distorted reality primarily to create missionary motivation at Apple rather than cover up his own weaknesses, and equally notably, his is among the rare criticisms of consultants that is fair, based on the breadth-over-depth tradeoff we consultants must make, rather than glib charges of default-parasitic evil tendencies (his opening line in the clip above: “I don’t think there is anything inherently evil in consulting”).

The key to immunizing yourself is to tag the primary source of the accusations in a give case, reject their default claim to the moral high ground (and default insidious suggestion that the consultant must necessarily be the parasite, kinda like a Butler Did It default), and uncover the actual pattern of parasitism going on.

Which might lead on to…

Fighting the Good Fight

Once you’ve uncovered it to your satisfaction, the actual pattern of parasitism in a weak organization is not necessarily information you need to act on. The organization may be naturally defending itself, and you may be able to add value without getting involved. You just need to become aware of it to protect your psyche against gaslighting, and dodge scapegoating attempts.

But if need be — and such need indicates the gig has turned into a war zone at a seriously weakened organization — you can choose to direct skeptical scrutiny where you think something is actually going on.

What weakness or fraud is a charismatic-but-weak leader hiding?

What processes are career bureaucrats protecting from skeptical inspection?

These questions are weapons with which you can go on the offensive if you feel things are going beyond generic knee-jerk gaslighting of consultants and you’re actively being set up for unfair blame.

That is, of course, if it is worth your while to stay and fight at all, not just at a personal level, but at the level of your sense that the organization has value to the world, is worth curing of its parasitic infestations, and that you can be a meaningful part of the cure.

This philosophical immunity is necessary if you want to survive as a consultant, because it is very rare for consultants to be hired to help completely healthy organizations, and very easy to buy into hostile “evil mercenary” perceptions of yourself.

Chances are there is a little bit of parasitic infection of all three kinds (in a large organization, even if you are playing a clean game, doesn’t mean other consultants in the organization are).

Internal Allies

Not every gig is a Mexican standoff of three-way competitive parasitism, and you don’t have to stay and fight in all of the ones that are.

But chances are you, you won’t have the luxury of always working for healthy organizations. Some fraction of your gigs will involve parasite-fights, and of those, you’ll have to pick a few to actually fight, because they are Good Fights.

If you walk away from all of them, not only will you forgo a big slice of the consulting pie, you will fail to grow in courage and integrity as a consultant. So you must pick a few fights. Every gig need not be an anti-parasite fight, but a few should be.

Still, it’s hard to fight the good fight to save an organization when nobody within it seems to want to. This means, it’s only worth fighting when you have effective and sufficiently powerful internal allies who are fighting for what’s worth saving about the organization.

Assuming you’ve philosophically immunized yourself against charges of parasitism, the three most common allies who make for a fight worth fighting in an unhealthy organization are:

-

An effective CEO/leader against an unaccountable bureaucracy.

-

A effective and competent bureaucracy against an unprincipled predatory weak-charismatic CEO/leader trying to feed on the organization.

-

An effective senior leader who is not the top leader/CEO but has enough personal credibility and sophistication to lead a reform campaign even despite an unaccountable bureaucracy and/or weak-and-charismatic top leader.

That third pattern is surprisingly common.

One of the tells of a weak-but-charismatic CEO is that they tend to allow high-level exceptions in their reality distortion field to make room for competent subordinates they cannot do without.

While their general leadership posture is demanding unquestioned loyalty from their inner circle, and cult-leader like reverence from employees and customers, who don’t see them close-up, they tend to compromise that posture where they must.

A good principle to remember this pattern is John Boyd’s advice: if your boss demands loyalty, give him integrity, if he demands integrity, give him loyalty.

Let’s call a senior leader who plays by this rule a Boydian Lieutenant. A holy warrior willing to lead the Good Fight internally. These make great allies and clients.

Extremely weak leaders, or ones preparing to exit with their loot (possibly killing the organization in the process), tend to demand loyalty and accept nothing but loyalty. But the ones with better survival instincts (who might have some genuine desire to keep the organization alive mixed in with profiteering motives), tend to make exceptions for indispensable Boydian Lieutenants.

They are the only ones excused from having to pretend to believe in the reality distortion field. They are the only ones excused from frequent and fervent inner-circle displays of loyalty towards the Dear Leader. They are the ones equipped to lead a Good Fight.

In summary: philosophical immunization against charges of parasitism amounts to recognizing the pattern of competitive parasitism that infects weakening organizations, correctly attributing unfair charges and gaslighting to competing parasites, and being prepared to go on the offensive and bring skeptical scrutiny to their behaviors when you feel the fight is a Good Fight, and you have the right internal allies.

If you have that mindset, the practical immunization is easy.

Practical Immunization

Once you have the mental models for philosophical immunization in place, are able to deflect routine gaslighting, and are armed with the information to go on the offensive if necessary, you are actually equipped to do some good in your gigs.

But there’s a matter of practical immunization. It is not enough to have the philosophically hardened mindset. You must structure gigs tactically for defensibility against false charges, insinuations, or perceptions of parasitism.

Here’s the key trick: make yourself hard to hire, hard to retain, and easy to fire.

(Hard to retain as in, hard to keep you paid, benched, and available without actually giving you things to do).

Most consultants and consulting firms do the exact opposite. They strive to be easy to hire and retain, and hard to fire.

Worse, they do all they can to structure gigs with hooks for passive income, unnecessary maintenance work done on autopilot, and front-loaded non-optional work as a precondition for working with a client. That last item is a particularly clear tell of a potentially parasitic consultant.

Example: a publicist firm I once worked with on a project many moons ago insisted on front-loading a $7500 item into the contract (we negotiated it down to $2500 and a cross-promotional barter clause) for taking a month to prepare a “Master Marketing Plan” before they did any actual publicity work. This sounded like bullshit, and what do you know, it turned out to be bullshit. That whole engagement was a huge waste of money. It generated no useful publicity. Classic parasitic consultants.

Being easy to hire and retain, and hard to fire, and acting to lock down your own income regardless of project outcome, makes you vulnerable to accusations of parasitism. And it creates the kinds of moral hazard that make such accusations likely to become true, even if they aren’t initially.

But it doesn’t make such accusations automatically true, just easy to level.

Hard to hire, hard to retain, easy to fire translates into this structural heuristic:

Rely only on inbound leads to get gigs, and within gigs, never do billable work that you’re not explicitly asked to.

For the latter part of the principle, you can always suggest options for various ways to achieve an end (including using your services) that might solve a problem the client has, but the choice is theirs. And you can always give them freebies at your discretion to build trust and goodwill, but the choice to ask for more of the same with pay is theirs.

The client should never be surprised by an item on an invoice, or feel like they were forced to sign off on it to get what they actually wanted done (unwanted bundling basically).

If you are able to follow this principle 100%, you’ll basically be 100% structural immunity to charges of parasitism, because you’ll be able to say with honesty (though I’ve never had to):

“You guys sought me out, I’ve done nothing you didn’t ask me to, I’m making no money on autopilot, I’m not bundling in shit you don’t want, and you can kick me out any time you like. How am I the parasite?”

If you cannot hit 100%, you’ll be vulnerable to the extent you’re forced to deviate from it.

At 100%, you are also well-armed to go on the offensive and cast a spotlight on parasitism elsewhere if the situation calls for it. This can be hard (but not impossible) when you are at less than 100%. Basically putting yourself in the role of “let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” Engineering a condition of “no skin in the parasitism game” makes you an honest witness of it.

Should you aim for 100% practically immunity in every gig? Depends on the weakness of the organization and risk profile. You can take calculated risks (and remember this is reputational risk that you pay for with character/integrity perceptions that might dog you for years, not mere financial risk within a single gig).

Every outbound pitch, every uninvited speculative proposal, every suggestion within a gig that could be perceived as manufacturing unnecessary billable work for yourself, exposes you to possible accusations that you are exploiting gullible leaders/managers (or colluding with corrupt ones) to parasitically feed on a weak organization.

I personally don’t like to play risk management games when it comes to reputation, so I’ve pretty much stuck to 100% inbound and 100% do-only-what’s-asked consulting, with no passive or bundled billables.

I let clients know upfront that they entirely control the pace of the engagement and volume of work. I do not set an expected frequency of meetings, a minimum number of hours, or structure gigs to include fixed costs like non-negotiable initial discovery research hours or ongoing “maintenance” hours, though in many gigs I’ve had the leverage or trust to demand such terms, and the cash flow pressures to make it tempting to do so. Occasionally I let clients pay for a block of hours upfront to ease their budgeting, but that’s about it as far as deviations from my pay-as-you-go model go.

The only real control I maintain over a gig is prioritization of work requests: I prioritize client requests based on overall volume. So if they want deeper, faster engagement from me, they have to choose to rely more on me overall. The more you actually rely on me, the more I prioritize what you ask of me, which usually leads to more reliance on me. A virtuous cycle of increasing meaningful entanglement. Conversely, the less they rely on me, the less I prioritize them, a cycle of gradual disengagement.

All this is neither about noble ethics (I’m not particularly noble) or some sort of subtle rainmaking stunt (as far as I can tell, this rule is a self-imposed tax that lowers my potential income). It is simple self-preservation. As an independent consultant, your reputation for integrity is pretty much the only kind of capital you have.

And if that gets tarnished, you’re done.

You have to either quit the game, or go over to the dark side of self-consciously parasitic consulting.

But I don’t want that, and neither do you. Because you and me, we’re in the game for the intellectual challenges it offers. We’re not parasites.

Whatever actual parasites say.