All that talk of kool-aid last week reminded me of a 2×2 from one of my earliest explorations of that topic, a talk I did back in 2012 titled Should You Drink the Kool-Aid? (slides, video). Here is an updated version, transposed from the startup key to the indie consulting key. It is meant to help you think about a very important question: How do you know the core things you think you know?

This is a central question for us students of the art of gig because indie consultants need to be aware of their operating epistemology in order to avoid buying their own bullshit and turning into unconscious grifters.

Startups and Gigups

It is no coincidence that a 2×2 from a talk about startups is easy and useful to transpose to a discussion of indie consulting. The two domains are so similar it can be hard to keep them apart in your head. In particular, startup knowledge also revolves around the same question. In both cases, the answer is the same:

How do you know the core things you know?

Definitely not in a scientific way!

Beyond the obvious surface-level similarities — small scale, financial precarity, cash-flow volatility — both startups and what we might call gigups share a deep feature: their associated modes of knowing are not science. Whatever the shared epistemology of gigology and startupology, it isn’t a scientific one.

If you’re an entrepreneur or an indie consultant, whatever else you might be, you are not a scientist. You may use or do some science along the way, but it will be peripheral to your core way of knowing. And crucially, if you want to succeed, you’ll find you can’t stop at the science. There is no such thing as an evidence-based startup or gigup. In the world of gigups and startups, only failures can be evidence-based.

The core of your real work begins where the science ends.

A strictly scientific self-image is self-limiting for an indie-consultant or entrepreneur, and can only hurt you. Looking for the secret sauce of a startup idea or an indie consulting offering only where the light of science can shine is to act like the drunk in the parable, looking for his keys where the street light is shining rather than wherever in the dark he dropped them.

This does not mean the native modes of knowing in startups and gigups are illegitimate or useless. In fact, thinking that, developing science envy, and trying to put a scientific gloss on non-scientific modes of knowing, is the surest way of destroying the kinds of legitimate value they do produce.

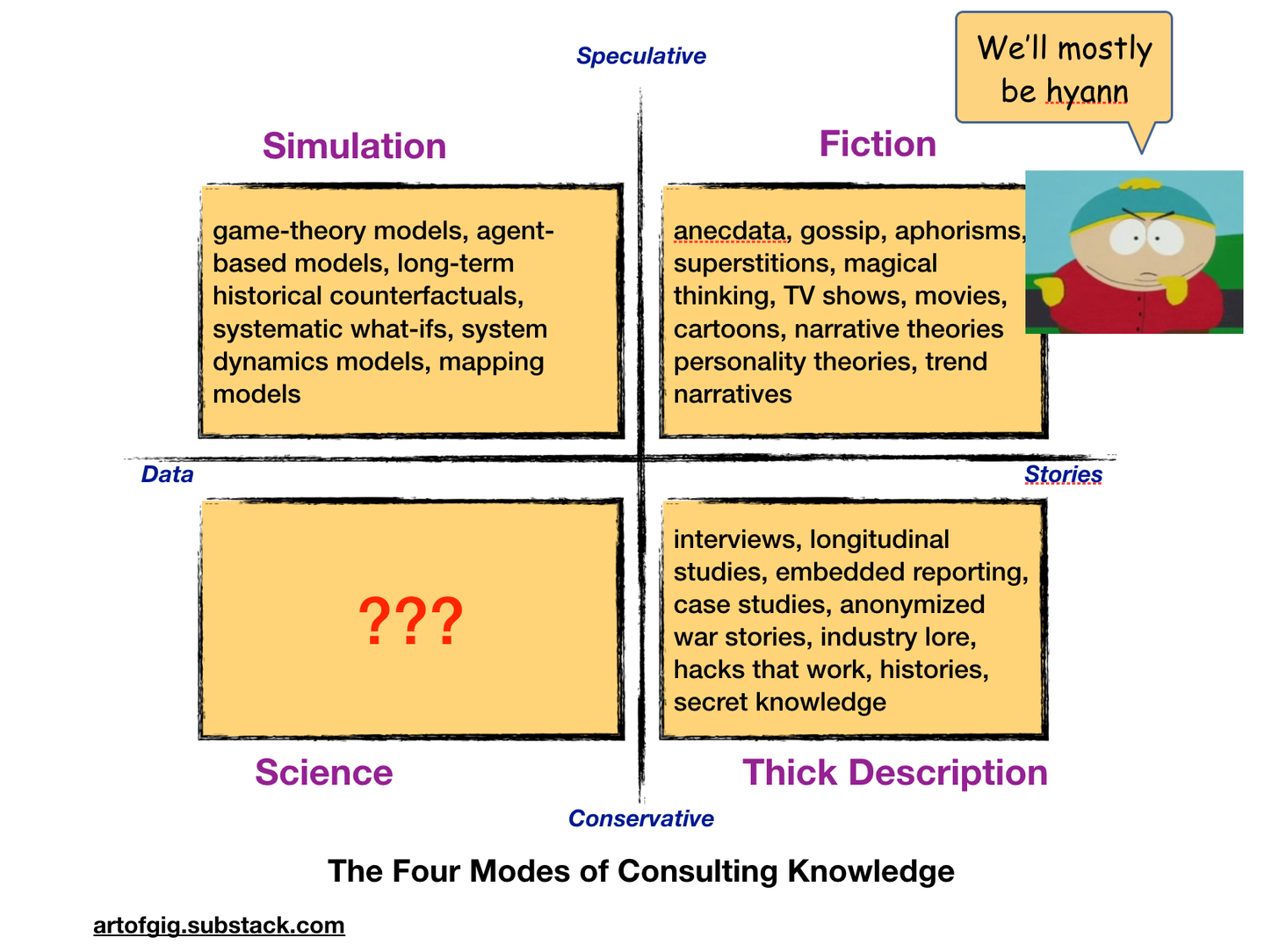

The 2×2 captures 3 possible good answers to the question How do you know the important things you think you know? — through fiction, through simulation, and through thick description (a fancy word for anthropology). None of these is science, but all of them are valuable modes of knowing.

Science, loosely speaking, is a conservative, data-driven mode of knowing. Indie consulting is speculative and/or story driven. The science quadrant of the 2×2 is ??? because there is, in a sense, nothing there that can be a core part of what you know as an indie consultant. This took me a few years to realize. In the original version of the 2×2 (which you can find in the slides linked above), I had some stuff in that quadrant that I was giving the benefit of doubt and labeling “science”. Now I’m convinced there is no there there. Just people performing various forms of science envy.

If there is science to it, it is not part of your core. If it is part of your core, it isn’t science.

If it’s a real science, there will be “pure” scientists working adjacent to whatever you’re doing (setting aside the parlor game of “who is the real scientist”) to whom your use of their output will seem like a profane “application”.

When it comes to gigups and startups, nothing important that you think you know is known in a scientific sense. In the process of going from:

The ball bounces this way because physics

to

Calculating how the ball bounces is valuable for Great Yak Enterprises because….???

you inevitably, and inexorably, go from science to something else. Whatever that is, to call it “science” is a distortion of it, and a disservice to it.

But in that ??? lies the core of how you do know things and add value.

The Price of Integration

Why is science lost in going from pure bouncing balls to applied bouncing balls? What is gained in giving up a purely scientific posture in what you’re doing?

In the simplest terms, science is “lost” because startups and gigups both require integrative modes of knowing, and the price of achieving effective integration is that you must necessarily go beyond the limits of scientific modes of knowing.

This may be a cliche, but science is reductionist by design, and this is both a good thing and the strength of the scientific mode of knowing. You take an ambiguous phenomenon, and carve out a piece about which you can make relatively unambiguous assertions. The reduction is not a bug or flaw: it is what makes ambiguity reduction possible at all. Ambiguity reduction is the point of carving out a piece to work with.

When you try to “science” a system, you don’t carve out pieces that are important, interesting, or useful. Those are merely nice-to-have features you can hope for in a carved-out piece, but essentially unrelated to whether or not you can “science” it well. The chances that you can “carve reality at the joints” in ways that conform to the contours of practical concerns are low.

You carve out a part that offers potential for systematic ambiguity reduction, and hope that when you go back (if you can go back) and integrate it into understandings of the whole, some of that lowered ambiguity will pay dividends in some unpredictable way. To bring science to a party is to take a leap of faith that you’ll be able to go from holistic to reductionist and then back to holistic. But “going back” is not guaranteed. It’s a bit like killing yourself, hoping to be resurrected in a stronger form.

Simulation, storytelling, and thick descriptions are integrative modes of knowing. When you’ve taken something apart and scienced what you can science (and that subset might be “nothing”), the real work of a startup or gigup begins (also, leadership in general).

Are all gigups startups? Are all startups gigups? Is one a subset of the other? We’ll look at that question in a future episode of Art of Gig.

Teaser: they are not the same, except in the ways they can fail. What makes them distinct is differences in how they succeed.