Should indies “eat their own dog food”? It’s a surprisingly interesting question, when framed correctly for indies, but at first glance, it doesn’t even seem to apply to us in the general case.

It’s not a beginner question. It’s one that is hard to appreciate at all in the beginning, but gets more and more important as you log more years in the game. By the time you’re at say 6 or 7 years, it can start to feel practically existential.

I want to frame the question in this post, and give you a chance to think about it, before sharing my own answer in a future issue. But first, we need to understand the principle in its ordinary business context.

In the regular business world, including both b2b and b2c, the dog-food principle holds very strongly. I’ll state it as follows:

Dog-food principle: When a product or service could be an input for the vendor of that product or service, it should be used by the vendor as an input

It’s of course a big cliche, but an important and broadly true principle nevertheless.

Part of the reason is obvious. It is not a good look when you, as say the maker of a productivity app, don’t use it to improve your own company’s productivity. It’s a bad enough look that you may not be able to sell your product at all.

Curse or Blessing?

Eating your own dog food is obviously not an option available to all businesses, but where it is, it should be exercised, otherwise you’ll have some very awkward explaining to do when you attempt to sell it. Often you have no choice but to exercise the option. It’s a forced option.

But whether forced or free as an option, is the dog-food principle a blessing or a curse?

When your dog food is not actually the best dog food around, the principle can feel like a burden. This is not merely a soft psychological effect but a hard financial one.

There’s a reason companies often have to offer steep discounts to make sure their own employees use their products over competitors’ products. The size of the discount is in fact a good measure of the size of the burden.

For example, where I went to graduate school, in Southeast Michigan, there were a disproportionate number of Ford, GM, and Chrysler cars on the roads (I drove a Toyota). Some of it was of course regional or company loyalty, but a good deal of it was due to the employee discounts.

Another example. A decade ago, when I worked at Xerox, we had to use an intranet content management system made by Xerox called Docushare. It wasn’t exactly the best product of its sort around. It felt like an imposition to some of us who wanted to use other things, like Sharepoint, which was officially a competitor, and integrated better with all the other Microsoft products being used internally for other purposes (Docushare may have improved since then, but thankfully I don’t have to use either product now).

So the dog-food principle has a general reputation as a burden you need to be compensated for shouldering. But this is because most products and services are by definition not the leaders of their respective categories.

That is in fact the discriminating factor between whether it is a blessing or a curse. When you are the market leader, or have a decent shot at becoming the market leader, the dog food principle works for you and feels like a blessing. But when you are behind, with no realistic hope of catching up, it feels like a curse. Or at least a significant liability.

When the dog-food principle is a blessing, it is generally a huge blessing. This is due to at least three positive effects.

-

First, there is the natural advantage of having a major customer — your own organization — in the design and development loop, allowing you to iterate and innovate faster than when you are not your own customer.

-

Second, using your own product well gives you a significant marketing advantage. “We use it ourselves — and look at how well it works for us” is a very powerful marketing position, since it counter-programs the default perception of moral hazard that accompanies all selling (this is why products try to borrow the dog-food effect when they can, like toothbrush makers claiming their brand is most preferred by dentists for their own use).

-

Third, where the dog food in question is an important component of the vendor business cost structure, eating your own dog food translates into a big cost advantage. Not only do you get your own product at cost, your employees are trained to use it well, and even hack it/adapt it (which also feeds innovation, reinforcing the first advantage).

The dog food principle is so powerful, if you’re an entrepreneur, it is worth actively looking for business ideas that can benefit from it.

Serving a customer base that does not include yourself is in fact so much harder, other things being equal, I’d estimate dog-food businesses have a 3-10x overall advantage over comparable non-dog-food businesses, in terms of risk/return profiles.

In many cases, the dog food principle is so compelling, it is the reason the product or service exists at all. Not only does Amazon eat its own dog food when it comes to AWS, for a long time, it was the only customer for the service.

Often this kind of value is so high, you can even give it away free to others, as is the case with many internal Google products which went on to seed open-source projects.

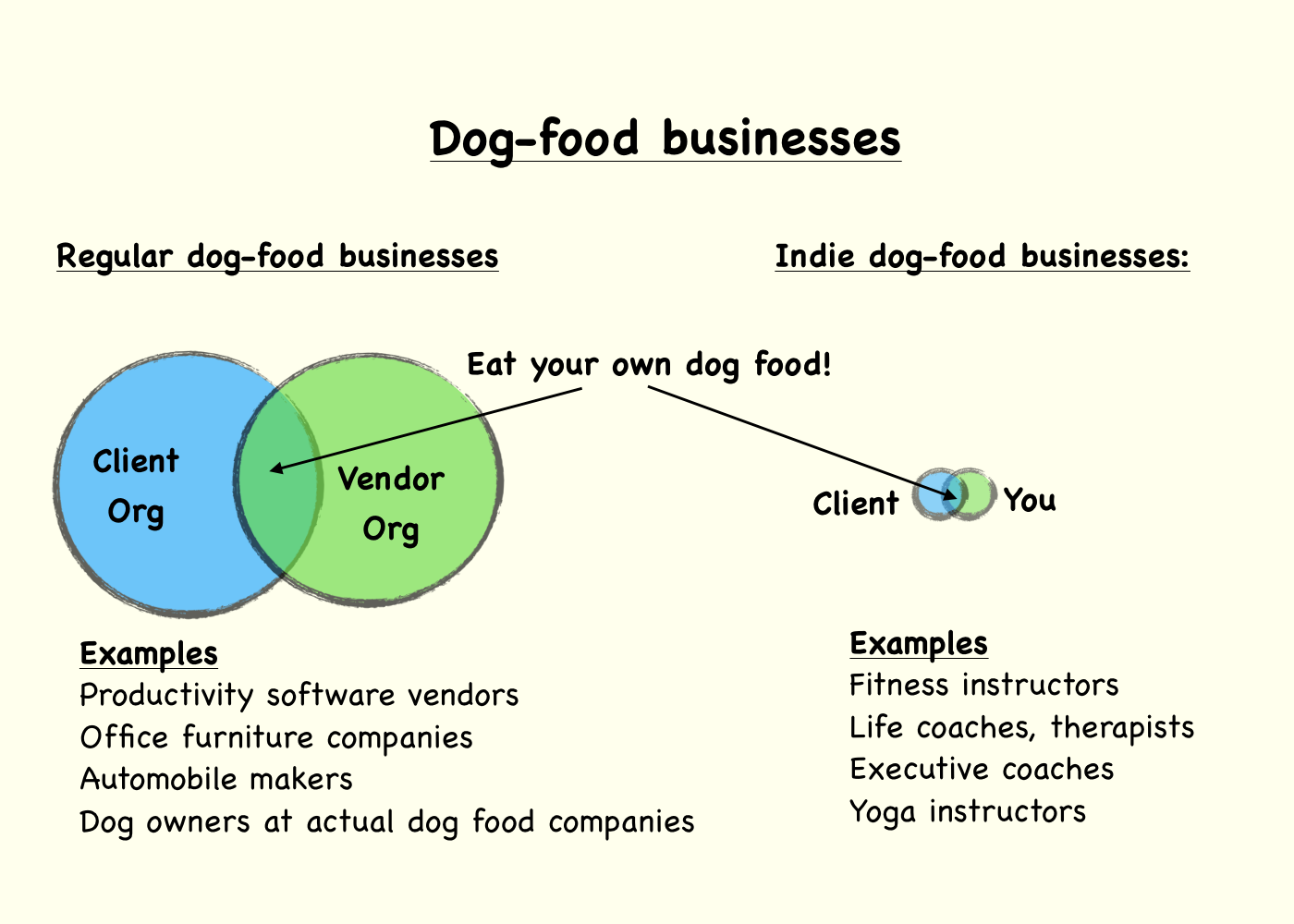

Here’s a picture. Dog-fooding opportunities exist where the vendor’s needs overlap with those of the customer. It’s not rocket science.

Obviously, the dog food principle applies to some kinds of indie businesses as well. Anything where the client is typically a single person retaining you in an individual capacity in their “whole life” context rather than their job, is typically a regular dog-food business, just at indie scale.

Fitness instructors should be fit. Life coaches should not have train-wreck lives. Therapists should be mentally healthier than their patients. Executive coaches should have leadership traits. Yoga instructors should be better at yoga than their students. Dentists should have good teeth.

Now when does the principle not apply? When is the deep strategic advantage not available? And what are the consequences?

Big Dogs, Little Dogs

Obviously, the dog food principle does not apply, and is not available for strategic leverage, where the idea/product/service is not an input for the vendor at all.

A cancer drug maker is not staffed by cancer patients for example (though perhaps cancer survivors or relatives of cancer survivors might be over-represented among the employees — this would be interesting to look into). A cancer drug maker has biochemists, lab equipment, computers, staplers, and coffee machines as inputs. Not cancer drugs.

But the more subtle case where the principle fails to apply is when the customer and vendor are significantly different in scale or scope of operations. This causes an impedance mismatch. The version of the product or service you sell isn’t the one you need yourself. Big dogs don’t have the same needs as little dogs.

When there is an impedance mismatch, similar business needs might be served differently, and a vendor or its employees might not use their own products for needs analogous (or even, at a superficial glance, identical) to those of the customer. This is not hypocrisy, merely specialization of needs.

-

For example, if you make large pickup trucks, it is unreasonable to ask all your employees to drive large pickup trucks, or offer big employee discounts to encourage it, since most people only need/want small sedans.

-

If you make large airliners, your executives probably should not fly around in large airliners where they really need a small executive jet.

-

Office printer makers should not expect their employees to buy them for home use (while at Xerox, I had a Brother printer at home because Xerox doesn’t make good home-sized ones, though they did offer an employee discount).

Knowledge-based service businesses are even more subtle. For example, have you noticed that big advertising agencies (so-called “agencies of record”) don’t advertise? Have you ever seen an Ogilvy ad?

Advertising, unlike the mass-influence-marketing businesses it serves, is itself a high-touch boutique relationship business, where sales happen via interactions between account executives and creative directors on the one hand, and CMOs on the other.

There would be no point to an advertising agency advertising its own services on TV. High-end advertising agencies are typically much smaller than the clients they serve. The latter also sell differently (through mass media, and large-scale distribution), to customers modeled in the aggregate as personas or demographic/psychographic groups. They do not sell to individual prospects modeled individually as in relationship businesses. So there’s no hypocrisy to advertising agencies not advertising.

At best you can look for more limited applications of the dog food principle. You wouldn’t trust an ad agency with a poorly designed logo or bad photographs on its website for instance.

Indie Double Jeopardy

It should be clear that the dog-food principle is generally not applicable to indies, either as a blessing or a curse.

For example, I consult on topics like organizational structure, business models, technology roadmaps, product strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Almost none of these topics is very relevant to either my personal life, or to my tiny 1-person business. The approaches I use with my clients would be cartoonish overkill for the versions of those problems I face myself.

Even where there is apparent commonality, there is likely to be a very strong impedance mismatch.

For example, companies big and small require web pages. But as an indie, your need for a website is very different from that of a Fortune 100 company. If you’re doing web design for big companies, it would be silly to pretend that a huge, complex, heavily trafficked website should follow the same principles as the typical indie consultant site (which might be a single static page hosted for free on Github, like mine).

But the effect is in fact worse than that. Indies face a type of double jeopardy because they don’t share a common input shared by all traditional businesses — being organized as a traditional multi-person business. This input is normally invisible, except during events like mergers and acquisitions between companies, when it becomes clear for example that “corporate culture” is a kind of dog food that matters when you try to sell the company itself to another company.

Not only do you, as an individual, not need the same inputs your clients need, or need them at the same scale or scope, you’re not even the same when it comes to ordinary human needs. You might legally be a corporate entity, but you’re really just a single worker, not an organization. And a very different kind of worker than an employee.

This means many basic inputs shared by all businesses are different for you, making selling to businesses twice as hard.

-

When a typical employee at a large company needs a stapler, they go look in the supplies closet or ask the office manager, making do with the standard stapler. When you want a stapler, you order one from Amazon, picking out one you like.

-

When a typical employee goes to work (pre-Covid edition), they go to an office laid out in an open plan that they probably hate. As an indie, you’ve probably arranged a pretty sweet home workspace for yourself.

-

A typical employee has many friends “from work” especially in smaller cities. As an indie, it is very unlikely that your friends circle and clients circle overlap very much. And if a friend becomes a client, chances are the client aspect starts to dominate.

-

A typical employee probably uses Microsoft Office at work. You probably use Google Docs.

-

A typical employee has to deal with a lot of day-to-day corporate bureaucracy. You are free of much of all that.

All these factors make it harder to “eat your own dog food” at a very basic level of business behaviors. You can’t even easily recommend a stapler!

Over time, it becomes hard for long-time indies to even relate to employees of client organizations and recognize their ordinary human needs in a business setting. Because you no longer operate in the context of a large organization, you lose the ability to operate in anything but an individual capacity.

Don’t underestimate the slow erosion of empathy and emotional and lifestyle distancing that occurs unless you do something, as you log the years as an indie.

The longer you’re in indie mode, the stronger the impedance mismatch between your needs and client needs, because you gradually lose the internalization of big-org needs at a business level, and empathy for paycheck employee mindsets and needs at a more fundamental human level.

You might say — it’s hard to eat your own dog food at a basic human level in relating to client employees because you slowly start turning into a cat.

You eat cat food while making dog food for them. Not only do you lack the dog-fooding advantage, you suffer a cat-fooding liability.

A sort of double jeopardy in short.

You’re not a b2b, b2c, or c2b business. You’re a c2d business: cat-to-dog.

Framing the Indie Dog-Food Problem

So we can now state the indie dog-food problem.

How do you apply the dog-food principle to your independent consulting practice, in order to realize the strategic upside, despite the lack of strongly overlapping input needs with clients, the lack of impedance-matched scale and scope of the few needs that might exist, and the growing human distance from employment-based lifestyles?

Or a shorter version: how can a cat sell dog food, and extract dog-fooding advantages out of cat food?

(Incidentally, as pet owners among you might know, cat food is in fact different from dog food. As obligate carnivores, cats can’t digest plant-based ingredients easily, unlike dogs).

Big hairy problem, isn’t it?

You might not see why it’s an important problem if you haven’t been in the game very long. But part of the reason so many people flame out so early in the indie lifestyle, and head back to employment, is that the lack of a dog-fooding strategic advantage (plus a cat-fooding liability) radically increases the crash-and-burn rate.

And if you do survive, the growing distance effect makes it increasingly hard to care about the kinds of problems businesses, and the people within them, face.

After all, you went indie in part to escape those problems in the first place. Learning to care about them again from the outside takes work, and can feel strangely perverse.

Left unmanaged, the indie dog-food problem can turn into a one-person “employee engagement” problem. You become disengaged from your own practice, slowly more ineffective, and start losing gigs. Eventually the practice can become unviable.

So how do you fix it?

I’ll share my own answer (I’m sure there’s more than one) in a future issue, probably next week.

If you’ve been in the game a few years, and have ideas about how to address the problem, take a stab at it. Either do a response on your own blog or newsletter, or if you like, send me your response. I might feature it in the issue where I share my own answer.