You may have noticed that a career in the gig economy is inextricably linked with lifestyle design. People who live off gigwork also tend to design their lives a lot more actively than paycheck people.

Why this confluence of gigwork and lifestyle design? It’s a historical moment thing.

People in the gig economy are at the vanguard of the world getting off a century-long artificial separation of human lives into producer and consumer aspects. We in the gig economy have been the early pioneers of the prosumer economy for a couple of decades now.

For normal people now uncomfortably cast into work-from-home mode, it is slowly becoming clear that we represent the mainstream future, rather than a present sideshow.

That that what they used to think of as “work-life balance” is a pale shadow of the real thing. That it’s something we figured out years ago, and they’re just beginning to wrap their minds around.

The Prosumer Moment

From the point of view of “normal” middle-class people fully invested in the paycheck lifestyle, gigworkers appear to unreasonably and perversely reject perfectly fine standardized consumption life scripts, scripts that have worked for a century for billions.

We have weird lives with lots of non-default aspects. We live in unexpected places relative to our personal and professional backgrounds. We have strange circles of friends, and associate with disturbing and sketchy people. We come and go unpredictably from the scenes we are part of. Our living arrangements and relationship patterns are illegible and confusing. We are a lot more freakishly invested in our side activities and hobbies than is seemly.

Our “normal” friends and family feel slightly embarrassed by us, and constantly feel the need to make excuses for us.

But we don’t lack respectability so much as being outlaws relative to respectability norms.

Ever so slightly, each of us undermines those norms by our very existence.

There is a general, undefinable air of slight disreputability to us, but it is a disreputability alloyed with a vaguely threatening presence that makes normal middle-class people uncomfortable rather than contemptuous.

Gig workers present as threatening counterexamples to the assumptions that certain scripts must be universal. Scripts that embody a way of life a majority of people, and entire developed societies, are very invested in.

We live prosumer lives that are hard to directly compare with the producer-consumer Joneses. Lives that are hard (and rather pointless) for others to try to imitate or compete with, due to the many bespoke elements.

For people living lives based on imitation and comparison, this can feel like an existential threat.

The Fundamental Theorem of Postmodernism

You could even make up an equation for this historical moment. I’ll call it the fundamental theorem of postmodernism.

Prosumerism = Gig work + Lifestyle Design

In some ways, this equation describes something like the pre-modern economy, where most work and life happened within the domestic sphere of agrarian life for most people, and working for cash in globalized markets was only a small part of life, relating to dealings beyond the family.

But in other ways, it is nothing like the premodern way of life. It is radically postmodern, and makes highly leveraged use of the most advanced capabilities civilization has to offer.

Instead of pointing to the vast majority of humans living very similar, miserable lives without modern conveniences like running clean water and well-stocked grocery stores, it points to a flourishing variety of lifestyles that combines the best of pre-modern and modern into post-modern.

That’s prosumerism as postmodern praxis (check out the Yak Collective report, New Old Home, for more on the home-design aspects of this)

We gigworkers and lifestyle designers are the true prosumers, and I want to claim the term for us. Which means kicking out the people who are currently squatting on it.

Prosumerism as Postmodern Praxis

The term prosumer has so far mainly been used in weak ways for ordinary paycheck-earning consumers who participate in minor, peripheral ways in the production aspects of things they consume, but are not employed in the production of.

This is just prosumerism as a form of shadow labor, an industrial lifestyle++ rather than something new. Bagging your own groceries, assembling your own IKEA furniture, completing surveys in exchange for gift certificates, entering contests to provide “customer-led innovation” ideas to companies. It’s all just ways for the consumer economy to sneakily make you do uncompensated, inefficient, low-value production activity for it, in the guise of empowerment and voice.

And the median human in the paycheck world is so disempowered, this feels like actual meaningful agency (check out Paul Ford’s great riff on this point)

The slogan of this kind of prosumerism is enter for a chance to win. Extreme couponing is what counts as lifestyle design within it.

So many layers of irony and existential despair folded into that phrase.

But there’s a better way to understand prosumerism: as an imaginative blending of production and consumption enabled by deliberately engineered and risky flexibility on both ends.

You need to do two things to qualify as a real prosumer by this definition:

-

First, you have to give up the perks of your paycheck job by going free-agent. That gets you production flexibility.

-

Second, you have to give up standardized consumption scripts as your source of status validation. That gets you consumption flexibility.

These are risky things to do, financially and socially. But what you get in return is enough flexibility on both ends to make prosumption worthwhile, and preferable to separated production and consumption.

If you have the imagination, you can use that flexibility to overcome the risks and come out on top.

This is the prosumer gambit. It is neither an exit decision, nor a voice decision. It is a way to cut your own personal deal with postmodern realities. Instead of playing the twin games of “employee engagement” and “customer satisfaction,” you make up your own game of living a quality life as a whole human.

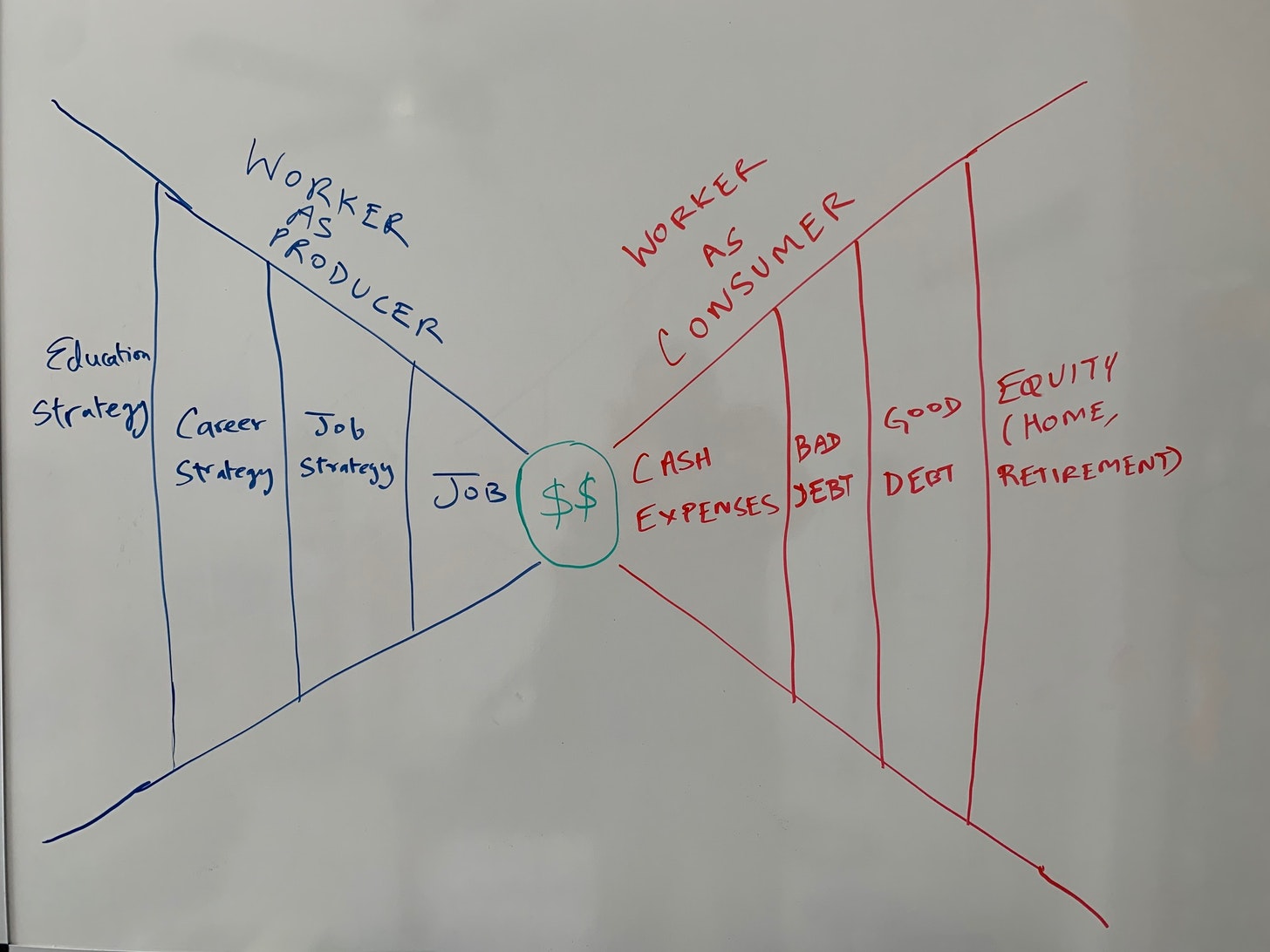

Let’s understand this through 2 pictures. I just got a nice whiteboard for my office so you’re going to get artisan, hand-drawn whiteboard drawings for this issue.

The Producer-Consumer Life

The paycheck lifestyle can be understood as 2 funnels that meet at their narrow ends, a producer funnel and a consumer funnel.

The paycheck lifestyle is a split-brain producer-consumer lifestyle bridged by the all-important paycheck as the conduit of all value. It is the corpus callosum of the 2 sides of your industrial-age brain.

The key point is that all work ends with paychecks, and all of life begins with paychecks.

Work-life balance is a cash balance. Ideally you want the equation balanced, or running a surplus. There is no other pathway for effort to turn into value. Cash is the enabler of all things, and the bottleneck in all things.

On the producer side, your job is your immediate income-generating activity. Behind that is your job strategy, which is how you maneuver for promotions and plum assignments within a job. Behind that is your career strategy, which is how you manage your job-hopping.

And finally, at the mouth of your funnel is your education strategy, which is how you charge up your potential energy to drive all the kinetic maneuvering at narrower parts. It’s education rather than learning because almost all of it is front-loaded into formal education. As you grow older, and time/opportunity for continuing education decline, you run out of potential energy and top out into your terminal career role. Learning in an open-ended sense is not naturally integrated.

On the consumer side, your life begins with immediate cash expenses. Then you have bad debt (credit cards, payday loans). Then you have supposedly “good” debt which may or may not be actually good — home mortgages and education loans. And finally, if you’re lucky, you have a zone of equity accumulation: home equity and retirement portfolios. These are passive for you. They’re not an actively managed part of the income/production side of the equation. Investment as income is for rich people. For the rest, investment is a build-up-when-young/draw-down-when-old/pass-on-to-kids activity. It’s part of the consumption side, as deferred future consumption. And it rests on the obviously false assumption of risk-free 3-8% growth embedded into retirement calculators.

Note that both sides are funnels with leak-proof walls and a directionality. You can only progress via linear stages from broader to narrower on the producer side, and narrower to broader (and more dangerously leveraged) on the consumer side.

There is no strong pathway for education to improve your life besides being converted into career strategy, then into job strategy, then into a job, then into a paycheck.

This isn’t necessarily a bad picture. It’s just a picture that’s a lot more attractive for a small minority of big winners than for the median person trapped within it.

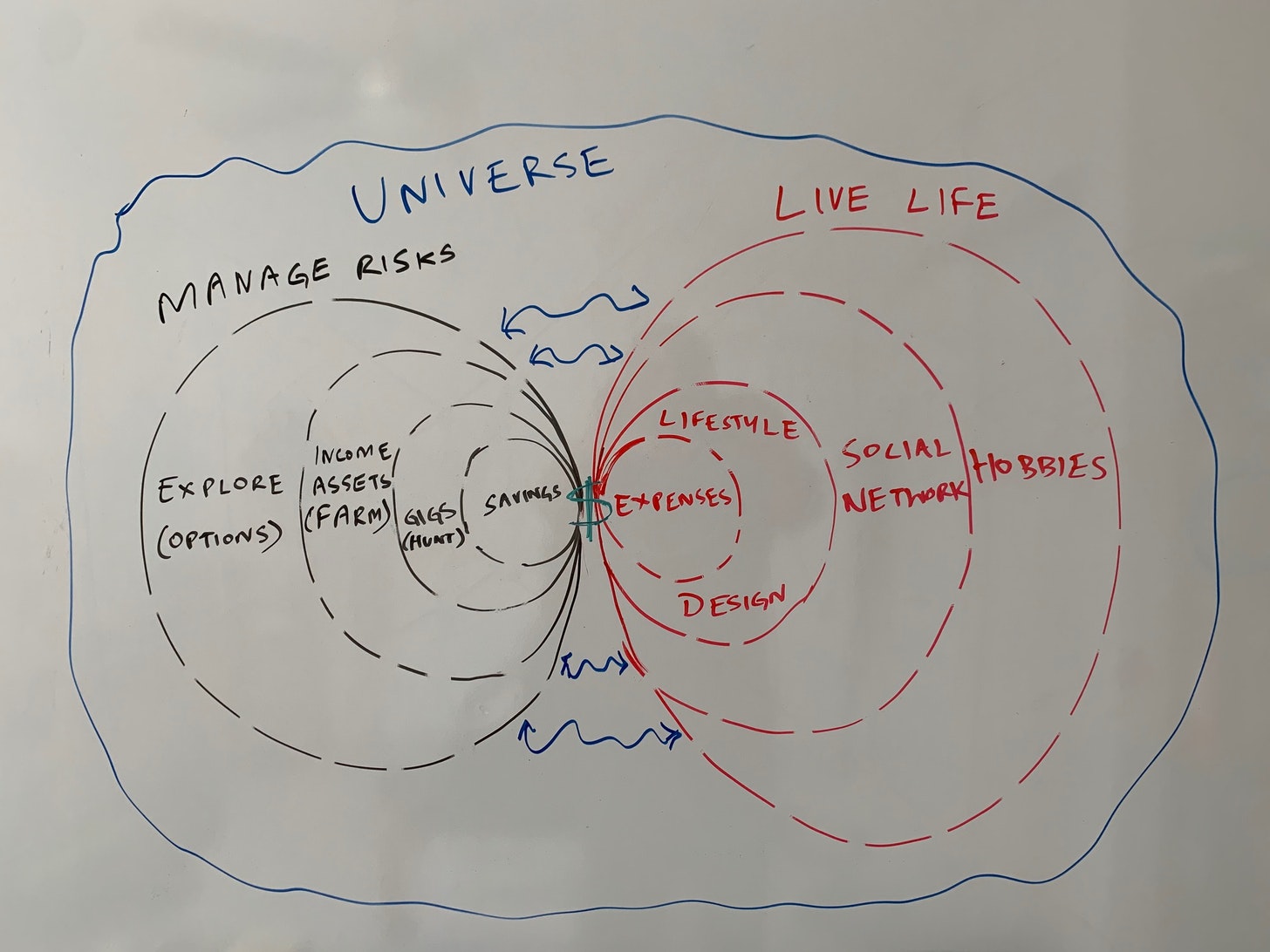

Now for the gig economy version.

The Prosumer Life

Now consider the prosumer lifestyle. It is tempting to map “gig work” to “producer” and “lifestyle design” to “consumer” and simply reproduce a relabeled version of the two funnels, but that’s not how it works.

There are two sides, but they don’t map cleanly to production and consumption. There’s a lot more going on.

They map, instead, to risk management and living life. Each side is a set of nested circles that again meet at the almighty dollar, but unlike in the two-funnels world of paycheck people, these circles have porous boundaries, and value can flow across the two sides of your life in much more open-ended ways, not just through paycheck dollars.

Here, there is no clear mapping of “work” on one side and “consumption” on the other.

For example:

-

You might start with a “hobby” (say astrophotography, something I’m getting into right now) that’s nominally on the “live life” side of the equation. There’s no significant risk-management involved.

-

There you meet someone interesting in the “social network” circle (say a fellow amateur astronomer at a star party). Note that it’s just one generic social network, not a “work” or “friends” network.

-

Then this relationship sparks an idea and bleeds over to the exploration circle on the “manage risks” side via a partnership to take a financial risk together (like pool funds to buy photography and telescope equipment, which is expensive and low-utilization).

-

That then leaks through to the income-generating assets circle where maybe the two of you create a website (say a site devoted to great astronomical photographs that also affiliate-markets telescope and photographic equipment, and offers a course on astrophotography or DIY telescope-making).

-

This makes some money that you then share.

It’s not that this sort of interesting story can’t play out in the two-funnels paycheck world, it is that it is highly unlikely within the two-funnel structure. In this particular example, astronomy is a night-time hobby that seriously disrupts a 9-5 paycheck job (and the associated evenings-weekends earmarked “family and social” time), but fits easily into a gig economy/lifestyle design prosumer life.

“Converting” the fun hobby into an income-generating asset is a much more natural thing to do as well, since gig economy people tend to not have values based on purist separations of work and play. For paycheck people, a “hobby” is likely to be a very sacred escape from “work” (says a lot about work as a psychic prison) that it would be profane to try to make money off of.

Collaboration is also easier. Paycheck people rarely have patterns of availability that allows for serious collaborations outside of their jobs.

Finally, note how risk management plays out here. Paycheck people have steady incomes, which means they have stable marginal values for both their time and money. If you make a $4800/month salary at a 40-hour/week job, every work hour is worth $40, and if you strive for work-life balance, so is every leisure hour. Which means you’ll want a significantly higher than $40 expectation to “sacrifice” a leisure hour on a risky venture.

But if some months you make $10,000 and other months you make zero, the marginal value of your time (and money) varies wildly around that mean. It is much easier to randomly throw a dozen hours at building a website that might make no more than a few dollars a month in affiliate commissions. It is much easier to simply take a low-value gig just to learn a new industry. It is much easier to get very seriously into a hobby during slow periods.

Consumption and Status

Don’t underestimate the status constraints of the consumption life-script side of paycheck lives either. For a paycheck person with a nice title and a house in the suburbs, who meets coworkers everyday (now on videoconference), keeping up with the Joneses and conspicuous consumption are inescapable parts of life.

It is much harder to “break status” and do schleppy things “beneath” your status, either at work or home. It’s like breaking character as a worker in a theme park.

For a paycheck person, it can feel seriously degrading to do things that would seem menial in relation to their work, like running a website with affiliate links, or teaching a self-published course.

Things paycheck people do outside of work must reinforce the status they project at work and in their communities (or at least, harmonize with it).

For a big, important Vice President at a major company, menial things — like say working with blue-collar tools — might only be acceptable if they are done as part of a status-reinforcing hobby, like building hand-crafted furniture in a garage workshop that’s kitted out with only the finest equipment. The idea that your workshop might be the backend of a side hustle selling little wooden boxes on Etsy can feel really demeaning.

If you’re a Senior Fellow as an experienced engineer at a famous company, you might only be willing to teach what you know if it is as an adjunct professor at a well-known university (even if it makes you little to no money relative to an equivalent self-published course). For a respected engineer, teaching and marketing their own course, without credits from a prestigious university attached, and without an existing pipeline of prestige-branded students conditioned to respect you, can feel demeaning.

But for a gig economy person, these sorts of things are what makes prosumption lifestyles both fun and flexibly risk-managed. When your marginal hour is worth anywhere between $5 and $500, and status considerations are much weaker in your life, you can do a lot more with all your time.

During a slow period on the high-end consulting front, it feels perfectly natural and fun to spend long periods of time doing “menial” things.

During a high-demand period, it feels perfectly natural to let work-life “balance” get seriously out of whack for a while, as you make hay while the sun shines.

When you tire of an activity, it feels perfectly natural to level up and turn it into an online course, so others to whom it is new, fresh, and interesting can take over what you used to do, and you can move on to your next adventure. It’s not about status as a respected teacher. It’s just another hustle.

At any time at all, it is easier to do what you want, rather than what a script tells you to do.

Beyond “Evenings and Weekends”

Chris Dixon once famously observed that “What the smartest people do on the weekend is what everyone else will do during the week in ten years”

Drew Austin recently tweeted a snarky version: “what hot people are doing today, smart people will be doing in 10 years.”

Chris’ version gets at the nature of the entrepreneurial escape hatch from the producer side of the paycheck world, driven by smart people jailbreaking themselves.

Drew’s version gets at the nature of status competition on the consumption side, driven by trends and fashions set by attractive people pwning the social status game.

What both have in common is that they accept as a given the central role of imitation in the producer-consumer divided lifestyle model. Work and life as competitions fueled by imitation, signaling, and envy. To win is to have others want to be like you, but without beating you.

The great allure of the prosumer way is to break out of the straitjacket of a lifestyle unnaturally divided into production and consumption aspects, each driven by its own patterns of imitation and competitive signaling. This is why going free agent feels synonymous with “getting out of the rat race,” even if you actually work a lot harder.

Done right, it can be a lot more fun, and a lot less rat-racey, while actually being more impactful than being the Joneses.

The first step is gaining radical control over your time. Everything else follows naturally.

What might a prosumer version of the line be?

While imitation is still a big piece of the puzzle (witness the huge subculture of Tim Ferriss imitators in South East Asia), it tends to be conscious, critical, and cautious imitation driven by pragmatic and strategic considerations, with a lot of experimentation and tweaking to make it work for you. When free agents take courses from each other, they tend to act like canny prosumer shoppers investing in themselves, not resume-stuffers trying to get an A+ with the lowest effort possible.

Imitation for a prosumer is not a simple matter of “I’ll have what she’s having.” It is imitation as strategic borrowing of a good idea as a starting point for life-energy investment. It is not some sort of depressing and gloomy trajectory of Girardian mimesis underwritten by a paycheck.

So a prosumer version of Dixon’s line is definitely not something like “what gigworkers do today everyone will do in 10 years.” We do represent the mainstream future, but not in that literal-minded way.

That would be a failure of this historical moment to live up to its potential.

Instead, it’s something like “what a gigworker does today will either not exist, or will exist in a hundred variant flavors in ten years.”

And that’s the real attraction of where this historical moment can lead us: to a world of flourishing variation and natural selection in life and work, instead of a world of depressing, in-bred, purebred dog-show sameness.