Jobs provide a ready-to-inhabit psychological home-away-from-home that a mere portfolio of gigs does not. Home, sweet office, as a refuge from home, sweet home. In a good political and economic environment, this is not very important. If your gigs are enough fun, and the local Starbucks or other “third place” is open, you might not even notice that you lack a psychological home for work. Not everybody is a homebody at work, or wants to be.

But when the economy and political environment go bad, being in the gig economy is like being caught outdoors in the middle of a winter storm. Then you notice. Suddenly, being indoors in a nice job offering home comforts seems really attractive. It’s not even really about the money. It is about having an intact social reality to inhabit.

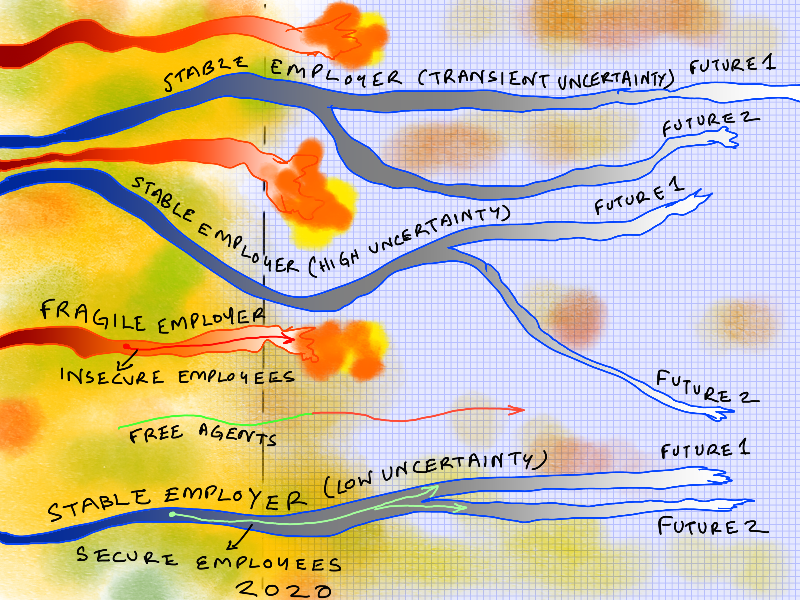

I’ve been trying to come to terms with this sense of being caught outdoors in bad political-economic weather. I made myself this little iPad painting to contemplate.

I’ll explain the picture in a minute, but some more general thoughts first.

Gig Economy Weather

Under normal conditions, when the economy and political environment are healthy, being in the gig economy is like being outdoors in a park in nice weather, with a picnic basket, and a clean bathroom nearby. The sun is shining, squirrels are running around. Birds are chirping. You don’t miss home, and in the moment, it seems like being outdoors is an obviously nicer situation than being cooped up indoors, at least for you.

Interactions with clients feel like they are happening across a window ledge: they are indoors, you are outdoors. You’re both happy with your choices. Indoors or outdoors is a matter of lifestyle tastes.

When the political and economic environment are really nice, you even get a whiff of a yearning for the outdoors from clients (I got this feeling sometimes in 2013-15). They are mildly envious of your freedoms. There they are, trapped indoors within the limited reality of a single organization, while you are free to participate in many realities in many organizations, and also to enjoy the broader economic outdoors with personal projects, writing about larger macro trends, and so on. That’s what good times in the gig economy feel like.

These are not good times. Lately, I’ll admit, in meetings with clients, I’ve found myself feeling mildly envious that they are indoors, within largely intact private social realities, while I’m outdoors in the midst of an unraveling public reality, facing the full fury of the politico-economic elements without a roof and walls around my work.

Dulce Domum

We are so used to thinking in terms of the work-vs-home dichotomy that we often lose sight of the fact that work is in fact a home-away-from-home. In a job, it almost always is literally so. You have a desk, or even a room to yourself, with access to kitchen facilities, bathrooms, and a bunch of people you probably like — your work “family” so to speak. If you work for a particularly paternalistic company like Google, there might even be good food, places to nap, a game room, and laundry. It might even be better than home.

In the gig economy, this home-like feeling may or may not exist. Perhaps you have a coworking space and regular lunch buddies. Perhaps the friendly Starbucks barista substitutes for the friendly coworker; someone you say hi to every day.

This feeling of being home-at-work (HAW) is important. More so than work-from-home (WFH). It allows us to relax, and trust the work environment to supply a certain amount of both material and social comfort. It provides a thoughtfully mediated sense of connection to the broader world. It fosters a productive and generative state of mind.

This is the sweet-home feeling, dulce domum. For work, perhaps we should call it dulce officium, the sweet-office feeling (my Latin translation might be off, but I’m sticking to it since I like the sound of the phrase).

What is this feeling like?

In Kenneth Grahame’s classic, The Wind in the Willows, there is a moving chapter titled Dulce Domum, where the two main protagonists, Mole and Rat, are making their way back from yet another crazy adventure on a cold winter night. They pass through a village with many people comfortably ensconced in their warm homes:

But it was from one little window, with its blind drawn down, a mere blank transparency on the night, that the sense of home and the little curtained world within walls—the larger stressful world of outside Nature shut out and forgotten—most pulsated…

Then a gust of bitter wind took them in the back of the neck, a small sting of frozen sleet on the skin woke them as from a dream, and they knew their toes to be cold and their legs tired, and their own home distant a weary way.

Thus primed to yearn for home, as they exit the village, Mole catches a whiff of his own home nearby, which he’d abandoned several months earlier, disgusted with chores and cleaning, to go adventuring. He is overcome by a powerful homesickness, and is inconsolable until the two of them find their way back to his home and spend some time there.

If The Wind in the Willows were a story about the gig economy, the village would be a business district full of offices full of people happy to be away from home, and the adventures of Mole would be gigs. The dulce officium moment would be a sudden yearning for a regular job, with lunch buddies, malfunctioning printers, and running gripes about bad coffee.

I occasionally get a whiff of that feeling now, when I peek into the lives of paycheck people, through client meetings or otherwise. They are secure in their warm jobs, inside organizations with their inner social realities largely intact, even if the material realities of work-from-home regimes have made the home-at-work feeling much messier.

For people with secure paycheck jobs, the reality of Covid19 has not yet fully hit, and possibly never will, no matter how long they work from home.

They are able to immerse themselves in the pleasant reality distortion fields of their jobs, within which the pandemic has been aestheticized and processed into a business crisis, complete with recovery strategy meetings. Hardship is of a familiar corporate sort — budgets cut, pay cuts, travel and events canceled.

Organizations do these things in the face of every crisis, so there is a certain ritual familiarity with the response pattern, if not the stressor. Paycheck employees are at home in their responses. Dulce officium.

You’re Exposed

Dulce officium is not the case for the gig economy. The much flimsier work-homes we construct for ourselves, out of a favorite table at Starbucks, lunches with friends, and occasional meetups, have fallen apart.

Even if your cash flow and gig work routines haven’t been impacted — mine largely haven’t — the overall sense of being home at work has evaporated. I definitely feel exposed and outdoors. So should you. In the gig economy right now, any sense of security is a false one, unless your talents naturally turn towards profiteering off black-market PPE supplies or something.

The main reason, of course, is that if you’re in the gig economy, strategizing the recovery is not an optional spectator sport for you, consisting largely of tracking what the CEO is doing. It is an unavoidable imperative, fraught with real risk.

You literally have to think for yourself right now, because it is nobody else’s job to do so. If you don’t, things could go really badly for you. Already, almost by instinct (which is a result of nine years of experience), I’ve made several quick, tactical moves that turned out to be really wise. I’d already be in trouble if I hadn’t thought of them, and moved very quickly to do them. Like the rest of you indies, I have no paternalistic organization prompting me to do the necessary thinking and acting, and no concerned manager asking after my welfare. So this is not idle speculation.

This political-economic environment really is dangerous.

You really are exposed.

Lack of tactical and strategic foresight will cost you.

Newbies have to be extra careful — lack of experience navigating uncertainty increases your chances of making bad errors.

For an employee in a stable organization, there may be some tough times, but trusting the leadership to do a good job navigating the crisis might actually be a reasonable option. If you think your employer will be among those that will crash and burn through the crisis, but you have solid marketable skills in job-like domains, you might still be able to avoid strategizing the recovery for yourself. You could simply look for a new job with an organization that seems set to recover strong.

Of course, this is also an option for some in the gig economy. I’ve already heard of several giving up and heading indoors to jobs. But for many, it is either not an option (you might have marketable skills, but just not in a job-shaped package), or you don’t want to. A little bit of both apply to me. My skills don’t fit jobs, and a part of me is convinced that “whatever doesn’t kill me makes me stronger” in this environment.

If I can make it through this thing, I can probably make it through almost anything. So despite the unpleasant political-economic weather, the challenge appeals to me.

A Mood Map of the Future

Let’s talk about the picture at the top. It’s a mood map of the future.

There’s of course a lot of very specific forecasting, mapping, and maneuvering you can and should do relating to how your particular corner of the gig economy is responding to the crisis. But underneath those practical tasks, there is a more important emotional self-regulation task you have to tackle: dealing with the feeling of being outdoors in a harsh environment, without an economic “home” to work out of.

You have to assess the general mood, your own mood, assess whether the fit is a positive one that lends you agency, or whether you need to work on your own mood (since you can’t affect the general mood outside of a small, local zone).

This is not an environment that will be kind to depressed listlessness and weak motivation.

I’ve tried to map the general mood in the picture above.

To the left of the 2020 vertical line, there is a diffuse but defined mood. It is a patchwork of red, yellow, and green (which signify what you think they signify). Against this backdrop, the futures of individual organizations are evolving, with much stronger internal reality-distortion field moods created by things going well or poorly. Each forking tube is a reality distortion field evolving in time.

To the right of the 2020 vertical line, the mood is not so much good or bad as it is undefined. Like in those movies set in simulated worlds where the character runs to the edge of the simulation and discovers an empty grid. It’s not good or bad. It just isn’t.

The future we thought we were inhabiting has been trashed. The future that we are creating right now is largely undefined, still very much under construction.

There’s a few defined red, orange, and yellow patches, but not much green. But mostly it’s empty grid space.

There is enormous opportunity in this lack of definition of course. It means the future is waiting to be invented, and as a free agent, you have more ability than most to participate in that invention. But there is also enormous risk and anomie in that lack of definition. That grid-like outdoors is a stark space, bereft of that lovely home-at-work feeling that normally keeps you going. No dulce officium there.

If you’re outdoors in this gig economy, this is your element. An undefined grid with patches of danger, and very little by way of soul-nourishing at-home comfort. You can peek in through Zoom windows at people enjoying such comforts, like Mole and Rat in The Wind in the Willows, but you’re not one of them.

Don’t let their sense of security contaminate your mood. They can afford it, you cannot. You need to maintain a much higher degree of alertness.

If you’re indoors, there’s a good chance (to the tune of 60% of businesses in California according to a news report I just watched) you’re with a stable employer, whose inner reality can actually withstand the collapse of the outdoor grand narrative, at least for a while.

Of course, if your employer was already in bad shape, there is a good chance it’s on the verge of crashing and burning.

The green-turning-red thin line outside of the corporate “reality tunnels” is a typical free agent trajectory in this environment. The green and red lines inside the tunnels are the trajectories of paycheck employees in organizations that are surviving versus failing respectively.

You’ll notice I’ve illustrated a fork in the futures of the 3 surviving organization. If an organization isn’t being killed by immediate existential threats, it is at least facing a range of possible futures. Some have a narrow range, some have a wide range.

The point of this map is not to make specific predictions, gesture at specific environmental realities, or suggest specific maneuvers and strategies. The point is to become sensitized to the mood of the environment, your own mood within it, and how it relates to the distribution of environmental risks and opportunities.

Specific predictions can go wildly wrong. Maps can be inaccurate. Maneuvers may fail. But the mood of the party is generally unmistakeable, and the mood you bring to the party is the biggest determinant of whether you weather the storm, whether it drives you indoors, or whether it destroys you.

So for the time being, there’s no dulce officium for you. Just a challenge to survive and thrive outdoors in bad weather.