Only 5 more newsletter issues to go before Art of Gig wraps up on April 30th!

This is the special AMA issue of the Art of Gig. Answers to 7 questions sent in by readers. They were all pretty challenging to field, but in different ways. It was a fun exercise, forcing me to really think about every aspect of the indie life, from subtleties hidden in mundane aspects, to in-your-face existential conundrums.

Here we go!

Q1. What framework(s) can I apply to convert money / hour to a scalable indie solution: money x product?

Traditionally, I feel like gig work and indie consulting can fall into a trap: At some point getting getting a higher pay rate takes more effort than just doing work at a lower rate. As a result, I’m trying to define strategies, pathways to transform the equation from mb+x=y (m = hours, b = rate, x = fixed price, y = payout) into a more scalable calculation, where payout is disconnected from hours. For example: [mb+x]*r = y (where -r- is reach).

In summary: how do I best compound the work I’m doing so I create the same reward but with lower hours? — Rafael Fernandez

Yes! This is definitely a trap. In fact, it is a vanity trap. The bill rate is the vanity metric for indies, but really has no necessary relationship to income or quality of life/work. Obviously, if you charge $1000/hour in theory, but only sell 1 hour a year, that’s much worse than charging $100 and selling a full available inventory of 2500 hours (approximately 52 weeks of 48 hours each). And if you burn up $10,000 in savings over 3 months to build a service/information product that brings in $1000/mo steadily with 1 hour/week maintenance, you’re making a nice, easy guaranteed $250/hour in steady state for low-marginal-effort work. We all do such calculations all the time. It is second nature to indies once you’re in the lifestyle for good.

But the issue is not modeling a money-making machine or flywheel in the cleverest way. It’s not even about reach (which just changes the slop and intercept in Rafael’s equation; it doesn’t actually decouple income from hours). The real issue is examining the assumptions underlying the design of the machine itself and drawing the right conclusions.

So how do you actually think about this? The thing is, it’s not a 2-dimensional problem (money, number of hours), but a 3-dimensional one (money, number of hours, and quality of hours). Most people forget about quality of hours, and solve the problem wrong in terms of just money and fungible time.

The 3 variables feed into 3 aspects of the problem that the machine solves:

-

What you’re paid as validation of self-worth. Your rate anchors your self-esteem, and serves as a signal of the dignity of your kind of labor to others, to the extent you talk about it. This is a valid thing to care about. It only becomes a narcissistic vanity trap when it overwhelms other considerations. People in the art/design corner of the gig economy tend to be particularly insecure about this, and vulnerable to the vanity trap.

-

How hard you want to work. This is about both quality and quantity, but people tend to reduce it to quantity because that’s the legible component of “hard.” Anywhere between zero hours (true passive income) to the Ferriss threshold (4 hours/week) to a nominal week (40 hours/week) to “passion level” (you love it so much you work to exhaustion continuously).

-

The dynamics of your market. How much demand is there for what you offer, and what the options are for structuring it in various ways that lead to various amounts of work? For example, a recorded self-serve workshop and personal coaching sessions are both options for serving certain kinds of demand, with different implications for quality of time/quantity of time/money.

To answer your question directly, the best way to compound your work with the same (or increasing) reward is to not work as an indie consultant at all, but think like a product entrepreneur. If you build the right product, then obviously you get the highest compounding rate, and if you automate and outsource enough, you get a genuine decoupling and can retire early.

In this game, your time is almost entirely devoted to a front-loaded heavy lift towards developing the product (“labor cap-ex”) that can enjoy maximum compounding growth. The rest is marginal maintenance labor time (“labor op-ex”) for the nearly passive income.

But I suspect you don’t want to do that. If you did, you’d be building a tech startup, not an indie consulting business. Part of the fun of indie consulting is that you actually enjoy your work enough that you want to do a non-zero amount of it, and in a way that you have a sufficiently varied inbound stream of it.

In other words, you’ve decided to like work.

You don’t want to reduce it to a one-size-fits-all no-maintenance-needed product, make your fuck-you money, and retire to permanent leisure.

So my suggestion is: work backwards from two variables: how hard you want to work (hours per week), and how much variety you want in those hours.

That’s the tradeoff. And your preferred mix of variety and time may not be available given market structure. If you want to work 10 hours/week, with each hour being a fascinating and unique high-level 1:1 sparring conversation with an interesting person, that mix may simply not be possible. You may have to choose between 10 hours/week doing repetitive maintenance work on a passive-income product OR 20 hours/week doing 2x of the sparring work at half the rate.

But working backwards from hours*variety is a sensible way to drive the problem-solving.

Variety is actually a focused way of thinking about quality of hours for indies specifically.

If you can make all the money you want in 4 hours/week, that sounds great, right? But if those 4 hours are cleaning sewers, maybe that’s not what you want to do for even 4 minutes/week?

Most people would consider time spent talking to interesting people, calculating cunning moves in high-stakes games, working on challenging technical problems, serving the needs of people they genuinely like, or artistic/creative thinking, as “quality time.” Adrenaline, dopamine, oxytocin, endorphins… all the good stuff.

Most people would think of time spent filling out paperwork, fixing bugs in old Java code, cleaning sewers, or opening doors for people at a snobby hotel while wearing a ridiculous uniform very boring and low-quality. That’s just cortisol all the way.

The key to quality differs for different personality types, but for indies (or at least those who choose the indie life) it tends to lie in variety. Variety is the spice of our lives.

Indies tend to be open-to-experience, curious people for whom variety is the big driver of quality time. We don’t just want to work fewer hours and enjoy them, we want the enjoyment to be varied.

So if you solve backwards from number of hours and variety in work, you solve for quality and quantity of time. If that doesn’t meet your financial goals, you may have to work harder for a while to get the mix right. If the equation doesn’t balance at all with a reasonable range of indie work parameters (you could probably charge anywhere between $50 to $1000/hour in the United States, but if your equation requires you to charge $100,000/hour to balance, you’re in the wrong game — go start a unicorn company).

So in summary, decide to like work, think about quality of hours, and solve backwards from quality and quantity of time to what you must do to make the money you need. If you can’t solve the equation for the game you’re in, change the game to one with a different risk/return mechanism, like building a startup, or a paycheck job.

Q2. I’d be interested if there was every a moment in which you more or less decided to turn away from integrating into any normal sort of existence. I sense four years into my journey that I will attempt to integrate somewhat but deep down know we’ll always be hanging out at some sort of “fixed point” on the edge of these worlds. — Paul Millerd

I don’t think I ever thought about it consciously, or had strong opinions about it, to be frank. I have very low need for “integrating” or “settling down” or otherwise acquiring the accouterments of normalcy. On the other hand, I don’t have a strong need to not have those things either. I am not particularly attracted to subversive or radical subcultures and “alternative” lifestyles for their own sake. I am neither actively conformist enough to want normalcy, nor cliquish enough to work harder to gain entree into a non-default alt scene so I can feel special and non-normie. And I definitely don’t think either crowd is superior or inferior to the other.

So the consequence of what is essentially social laziness for me has been — I basically do what I want based on my appetite for risk and reward at that particular time/situation in my life, and sometimes it looks normal to others, sometimes it looks weird. Sometimes subcultures adopt me as one of their own, and at other times they reject me as a normie.

Neither of those effects bothers me. The people I enjoy hanging out with and talking to tend to be indifferent to those things as well, and are a chaotic, changing mix of normies and non-normies.

I once tweeted that “normalcy is just the majority sect of magical thinking,” and I think that captures the essence of my philosophy. People think being “normal” comes with a lot of things that it actually has no relationship to, like security, happiness, convenience, low effort, good friends, community life.

Normalcy promises all of those things, but actually delivers reliably on none of them. To the extent you seriously want some very particular mix of those variables (I don’t; I’m happy with many mixes), and you solve for them relatively reasonably, you’ll end up with a solution that may or may not look “normal.”

It’s the same with being “alternative” in any way. Same kind of promise, same lack of delivery. Except that in the latter case, there’s a premium fee and brand appeal associated with chasing the vaporware.

Which means that normalcy and alternativism are things you have to value for their own sake.

Which is fine.

“Desired lifestyle” is an independent input variable into the optimization cost function, with its own weight. It’s not the dependent variable that comes out the other end.

As far as I am concerned, there is zero difference between wanting “normalcy” versus wanting a particular kind of “alternative” life like being in a biker gang, an emo music scene, or a global nomad-worker scene. “Normal” is just a lifestyle narrative aesthetic that has majority appeal. Alternatives are just ones that have a minority appeal. Different narratives come with different aesthetic features and price tags.

So another way of summarizing my answer is — I put a very low weight on the narrative aesthetics of my lifestyle. So long as it makes sense and works for me, and I’m able to keep the friends I want to keep, I don’t need it to look good. Either to me or to others. As it evolves over time, it might look more or less similar to more consciously crafted narrative aesthetics by accident, but there’s no real design input on my end.

Any resemblance to any Branded Narrative Lifestyles™ living or dead, is purely coincidental. No identification with actual subcultures is intended or should be inferred.

But again, it is a valid thing to weight more or less. If you want to give it a huge weight, that’s fine too. That’s what strongly involved subcultural types, where the lifestyle narrative aesthetic borders on a LARP, do.

Q3: What is your suggestion for managing and writing about ideas that can span years and decades on one’s blog? Do you print your older posts and review them? Do you edit older blog posts and essays when you find mistakes or ideas that need clarification? How about your process for turning series into books. Do you ever outsource that? Do you have an editor? — Ryan Nagy

[Preamble: This question might seem off-topic, but I decided to answer it because is actually a good and important question for all indies. Writing and publishing are now basically a cost of doing business as an indie in most cases. So it is a very good idea to not just take it seriously, but learn to enjoy it.]

I basically almost never go back and read my older writing, though I reference it a lot through back-linking, based on what I remember saying. I only go back to read if I want to reference it, but can’t remember what I actually said. I almost never edit old posts or fix bugs. If the topic is evergreen enough, and I am interested enough, I might do a new bit of writing as a sequel, but I don’t think editing/updating/maintenance is fun enough for me to do much of it.

I don’t have a systematic process for ebooks, but yes I do outsource it. I’ve worked with 4 different partners for 10 ebooks. I’ve had copyediting done on some, others I’ve copyedited myself, and others, I’ve pretty much just put out as-is. My minimum standard is the Amazon Kindle store flagging typos and threatening to unpublish my books if I don’t fix them :). The whole area is unfortunately still pretty janky, requiring significant human TLC to produce even a low-production-quality ebook.

This is honestly in uncanny valley of effort for me. Neither my online archives, nor my ebooks, are a big enough source of either identity or income to optimize to death. But neither is it a trivial enough source of either to entirely ignore.

I think production effort for writing, in any medium (blogs, newsletters, books) should be in proportion to:

-

Identity salience: Creative work is part of your extended identity, so simply caring about how it looks is a legitimate thing, and people have different minimal standards. My minimum for basically everything, if I can get away with it, is “shitpost,” while others want even their most trivial thoughts to be carefully refined and quality-controlled, and beautifully packaged and presented.

-

Real risks: you don’t want to make mistakes if your article or book is teaching people how to do brain surgery or fix nuclear reactors. I don’t write about anything that risky. But if I did, I’d care a lot more.

-

Ambitions: if you want to hit the New York Times bestseller list, you need to do a certain level of production. I don’t.

-

Marginal upside: Will another round of spit-and-polish garner 10x more page-views or 10x more sales of ebooks? Or are we talking 10%? Or 1%? In my case, the answer is usually 10%, not 10x. Not worth it. Not not worth it either. My laziness breaks the tie and I usually decide it’s not worth it.

-

Marginal downside: Will another round of spit-and-polish prevent disastrous reputational impact and social death because you have a tendency to make non-PC jokes that might get you canceled? Or will it merely lose you a couple of OCD grammar bureaucrats who care too much about you’re commas and apostrophe’s? In my case, the downside is limited because I don’t have radical, heretical thoughts burning a hole in brain, trying to sneak out and burn everything down. I’ve not really had to watch what I say to stay safe.

And as for managing writing over the long term for internal reasons, working effectively on a large body of evolving, interconnected thought — I actually think it is best not to manage it at all. Anarchy is my ideal. If something is important enough, you’ll remember it, and it will turn into a through line in your work organically. If you forget it, it wasn’t important. If a connection between two ideas is salient, it will keep crossing your radar until it forms a synapse in your head. If not, the connection doesn’t need making.

This probably sounds more like rationalization of laziness than it is. I’m not that unconcerned. I genuinely think active management of long-term habits of thought does more harm than good most of the time. Let your mind find its natural cowpaths, then pave them.

That said, it is helpful to nudge the process along by using a decent system of backend notes (what Tiago Forte calls a “second brain” — he’s writing a book about it that features in Q5) to store more raw material (including raw material generated by long-ago you) than your first brain can hold, and make sure it churns in and out of your attention in a sufficiently rich way.

I’ve used a variety of media for that over the years, but it’s generally been too chaotic to call a “system.” My current secondary medium is Roam Research, which I highly recommend. But my primary medium is actually my public blog, Ribbonfarm, which is more of an over-produced private notebook than the under-produced publication it pretends to be.

But beyond capture and storage, the rest is basically optional. Create a sandbox, then let your mind play in it.

Q4: What’s the best way to learn more about People School of thought? — Steven Ritchie

For those who are wondering what this question is about, there are two major schools of management consulting, the majority Positioning school, represented by (for eg) Harvard Business Review, McKinsey, and Michael Porter, and the minority People school, represented by a more rag-tag bunch of academics and practicing boutique and indie consultants. The basic background on this important distinction is in the book Lords of Strategy by Walter Kiechel, which I reviewed here.

I wrote an early Art of Gig issue about this (A Tale of Two Schools, May 29, 2019) which I just un-paywalled for this AMA issue. The tldr of that post is — there has been a war brewing between the two schools. Both school represent opposed Great Truths, so whatever directions your sympathies lie, you should be prepared to make your own yin-yang synthesis and ride out the war. My own prediction is that the People school will slowly gain ground, and a new equilibrium will be established that is 80-20 in favor of the People school side, as opposed to the current 20-80 against.

The People vs. Positioning battle is one front in a bigger trend that goes beyond the indie/gig economy, the rise of what I call 5th generation management. I did an issue of my Breaking Smart newsletter on that.

With that background out of the way: how can you learn more about the People school (a very good objective — learn more about the likely winning team)?

Besides reading some of the material I’ve linked to and following the trails from there, the most important thing you can do is to literally focus your learning on people!

The Positioning school is rooted in economics, the People school is rooted in sociology and psychology. So basically, anything that improves your instincts and intuitions on the latter helps. Whether it is TV/movies, literary novels, or the psychology of game design (as opposed to economics-style game theory), it all helps. And there’s of course plenty of explicit management literature from the People school (see Kiechel’s book for a host of starter references; my favorite sub-school within the People school is of course the Boydian OODA loop/maneuver warfare body of literature, which is also the mainstay of my own consulting practice).

This does not mean you should ignore the Positioning school, but your learning about it should be driven and framed by your overall People-school mental models. Ideas from the Positioning school make for good servants, but poor masters.

But above all, to increase your rate of People school learning — spend more time with actual people! As many different kinds as you can. Talk to them, be interested in them, understand their various nerdy obsessions, sit in on their meetings even if you don’t understand half of what they’re talking about, visit diverse organizations (in person or on Zoom), and so on. Devote most of your time to that end of things as opposed to reading the Wall Street Journal/HBR/Financial Times or building spreadsheet models based on balance sheets and annual reports or abstract reified analysis models like Porter’s 5-forces or “Value Chains.” Those things are important, but should be kept subservient to your People thinking.

That’s all there is to it. The People school is basically just being interested in actual people rather than the numbers that model them in economists’ models.

Q5: I’m approaching the completion of… the Building a Second Brain book. Manuscript is due in 3.5 months, it’s about 65% done, and now has a clear shape and identity. I’ll spend the next year and the first year after launch promoting it, and then sales will hopefully continue over the following years. It feels like the culmination of 5 years of my career, but really the last 10 years of my life.

I usually have a good sense of what’s coming in the future, and I look forward to it. But I’m having difficulty seeing past the event horizon of this big milestone in my life. I can’t imagine doing anything as important, impactful, or challenging, so every future past the next few years I imagine feels like decline and stagnation. I guess this is what they call a mid-life crisis!

What’s your advice for indies who are on the verge of reaching their fixed point ? Which for me has been to get this book published at all costs. What is meaningful to reach for once the biggest goal is realized? — Tiago Forte

For background, Tiago is referring to the idea of planning your future around arbitrary, idiosyncratic, highly personal “fixed points” such as home ownership or other personally meaningful goals, such as creative projects (in Tiago’s case, the book he’s writing, or in my case, wanting to pursue amateur astronomy more seriously in coming decades).

I explained (and recommended) the fixed points approach in last week’s issue as an alternative to more analytical approaches trying to “optimize” your lifestyle design with spreadsheets to maximize money or minimize hours, which I consider a depressing and nihilistic approach.

So, the answer to Tiago’s question…

“having difficulty seeing past the event horizon of this big milestone in my life” is the biggest feature of fixed-point thinking, not a bug!!!!! There’s nothing to fix here!

The whole point of thinking in terms of fixed points is that they give you a finite horizon that is not a means to some further end that lies beyond! It’s a way of solving the infinite regress problem. The fixed point in your life plan is an end in itself, and to the extent it is a meaningful end, it should create a blindness to what lies beyond! A good fixed point should feel a bit like a death wish; a horizon of self-annihilation! It should cause life-and-death levels of stress as you approach the big moment.

Why?

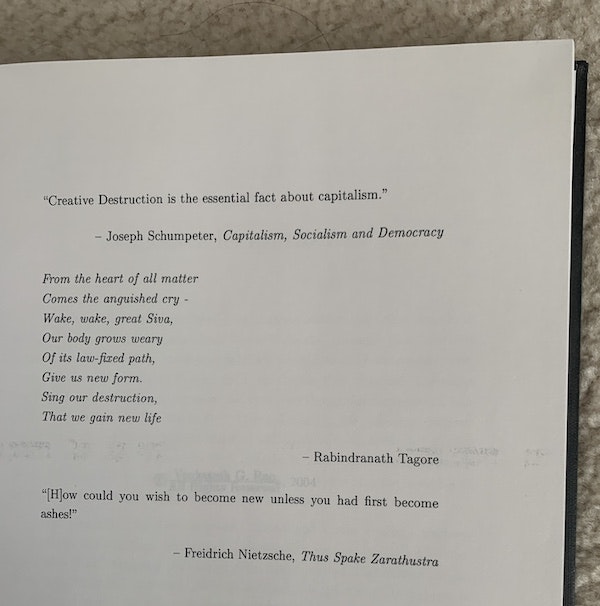

Because meaningful goals utterly transform you. You will come out the other end an entirely different, reborn person, working with a clean canvas on a resurrected life design. I felt exactly as Tiago does while I was finishing my PhD in 2003, and felt it so strongly that the feeling showed up as a set of quotes with which I opened my thesis. Here is a photograph (this is the first time I’ve cracked open my thesis in a decade I think)!

“How could you wish to become new unless you had first become ashes!”

Indeed. Quite so. Couldn’t have said it better myself Friedrich!

A good metaphor for keeping this in mind is that of a compass pointing to “True North.” What happens if you actually reach the magnetic north pole? The compass needle starts spinning uselessly! Every direction is (magnetic) “South” so the dipole has no way to align to a particular direction. It’s like a division-by-zero error. A singularity. A self-annihilation.

And this is a good thing. Now you’re free to pick a new direction, a new fixed point.

The problem would be if you didn’t have the blindness past the event horizon. Then I would doubt whether you had in fact discovered a meaningful fixed point in your future. If you can see past it, it’s a means, not an end.

So tldr — Tiago — you’re needlessly worrying about what is in fact the strongest proof that you’re working on a highly meaningful fixed point future that will transform who you are. Like Gandalf the Grey became Gandalf the White after his death-and-resurrection battle with the Balrog.

See you on the other side as Tiago 2.0! Burn Tiago 1.0 to ashes!

Q6: With the creator stuff, I imagine you could charge $10 for art of gig and likely not impact signups. How do you think about pricing and how much you make. I get the sense that you could push 15% harder and easily make more but that you have some deeper principle that knows this is ultimately not worth it. — Paul Millerd

Pricing is a complex, technical, and subtle topic when you are working on the corporate version of it. I just came out of a client meeting where we were discussing the nuances for their business — computer hardware. It gave me an actual headache, juggling the complexity of the model’s parameters in my head. It’s hard stuff, but I’d say most indies with some math training are capable of grappling with even the toughest versions of it, given some aspirin and domain knowledge.

But pricing for indies is only complex if you want it to be. If you recognize one central fact — that what you are selling is a piece of yourself — it becomes very easy indeed. No math needed.

In my case, pricing is primarily a proxy for the kind of formal or informal contract I am entering into. A $5/month newsletter sends different signals and sets different expectations than a $10/month. Since $5/mo is the minimum Substack allows, pricing at that point sends a very simple message — I want to make money, but do so while making the writing as humanly affordable as possible, so the maximum number of interested people can access it, short of it being actually free. Any number above that sends different kinds of signals about what I think my thoughts are worth, what I think it should be compared to, who I think my audience is, and what my calculations are about the revenue-maximizing point (whether or not they are correct).

The same kind of logic applies to pricing my consulting services. Currently I charge $450/hour (I started at $150 for my first gig, and I revise it every couple of years, but it’s been stable at this point for 3-4 years). It is probably not the revenue maximizing point (I could make more overall if I charged somewhat less and said yes to everything; my current yes rate is probably 50%). Neither is it the most I could charge that the market would bear. That limit is probably $1000/hour right now. Above that I’d be hard-pressed to sell any of my time.

For me, my current rate is the rate that sets the expectations I’m willing to let myself be bound to. Less, and I’d get too much inbound, and more importantly the wrong kind of inbound — stuff like life coaching or early-career advising that I have no interest in or talent for. I’m primarily a resource for experienced people. More, and I’d feel under more obligation/pressure to “create value” than I want to subject myself to. If I accidentally create more value than I am charging for, I’m happy to let others have the surplus. Nobody ever leaves money on the table. Other people take it. And if you like them enough, it’s okay.

So yes, I do have a “deeper principle,” though I don’t know how “deep” it actually is. It’s the same principle as the one I used in answering Rafael’s question earlier in this AMA — solve for quantity and quality of work, and begin by deciding to like working.

Most people who land on the “maximize income” trajectory (money solvers) or “maximize bill rate” (vanity solvers) do so by unconsciously starting from the opposite commitment to themselves: they have decided to not like working. They are working for fuck-you money (or what is almost the same thing, fuck-you fame) same as boring careerists and second-rate entrepreneurs solving for an “exit” rather than the next level of their mission. Working to stop working. A finite game.

Me, I work to continue working. Infinite games ftw. Not very hard, admittedly, but I don’t solve for stopping.

Once you decide to like work, and solve for both quality and quantity to make it sustainable indefinitely, it becomes obvious that solving for maximum revenue OR for maximum “status” as indicated by bill rate, is a very dumb thing to do.

And while marginal effort/value calculations are good to do, I don’t think the value side of that calculation should be measured in terms of money, because the cost side is being measured in terms of who you are, and what you are becoming by selling little bits of yourself at $X/hour.

Ie, “15% more work” gets me… 3x more something, and that something should be the kind of trajectory of being/becoming that feels most enriching to you, once you satisfy baseline economic/lifestyle needs.

This is a more convoluted way of saying, “solve for return on personal growth.”

So the formula is:

-

Decide to like working, and to continue doing so indefinitely

-

Figure out the quantity/quality mix of work that will allow that

-

Optimize marginal effort equations for personal growth, not money

It’s really not that hard once you’re past the bare subsistence level of the struggle (which of course I have deep sympathy for; having been there, and having a non-trivial chance of being there again).

For what it’s worth, I think you (Paul) are doing exactly that, based on your writings, so you already follow some sort of equivalent principle.

Q7: You’ve been pretty open on twitter about the emotional toll of Covid – Are you still reading the plague as a major bell-bottom bummer? How would you describe your approach to this dysthymia? Is it the adoption of new fixed points, or is there anything else you’re doing to get re-enchanted? — Paul Sas

Well, I do play a certain campy character on Twitter, which is some sort of grumpy-emo-uncle, but there’s some truth to that persona beneath the theatrics. For example, throughout the last year, I’ve been using the “Tonight at 11… DOOM!” Futurama gif a lot. That’s… mostly theater. It’s not like every time I posted that gif I was actually feeling overwhelming doom. I was on my couch tweeting, not working in an ER or trying desperately to log on to the unemployment website.

But OTOH, I’d say my overall reaction to Covid, modulo campy Twitter theater performance, has been pretty WYSIWYG. When I’ve sounded upset over the last year, I generally have been at least a little upset.

My approach to this dysthymia is to give myself permission to actually experience it as completely as I can. Unlike personal depressive episodes, Covid is genuinely a once-a-century systemic shock. The dysthymia is collective. A deeply shared experience. You’ll likely never be more connected to the rest of humanity at large as you are through this pandemic. There’s never been a sharper, stronger reminder of the connectedness of our fates and the importance of choosing compassion and pro-social attitudes to life. It’s weird to not allow yourself to experience it and make meaning out of it. Going by the historical record of the Spanish Flu and the Black Death, this dysthymia is going to turn into a sort of irrational collective euphoria and exuberance once the danger is behind us, but the shock and damage will continue to unfold. Changes will still be needed and will happen, even as depression inevitably turns to hypomania.

My approach has been the same for all of what I’ve called the Great Weirding of 2015-20, but I’ve held to it particularly through Covid. I don’t believe in beating an analgesic retreat, or what I call “waldenponding.” That doesn’t mean I don’t believe in self-care or emotional self-regulation. Those are important things. I just try to do them without retreating from the reality of the situation, because that makes second-order responses harder and worse.

While I do believe in emotional self-regulation, the style of such regulation I am fond of is more towards the gonzo side than the stoic side. I don’t place a particularly high value on inhabiting a narrow emotional range with an average position at Aurelian equanimity maintained with might striving. In fact, I believe that’s a kind of undeclared retreat. It is emotional self-regulation turning into emotional self-repression.

Interestingly, as a natural low-reactor without a huge emotional range, either internal or expressive (typical INTP in short), even campy theatrical emotional responses don’t come very naturally to me. Emoting is something of a learned skill for me. It’s of course easier on Twitter, where it’s all emojis and text and gifs, but I wouldn’t be able to pull off that kind of gonzo cringe-clown act in person.

Of course, seeking new fixed points and re-enchantment in a post-Covid world are important second-order responses, but the only way those will have a generative depth to them is if your first-order approach to experiencing what we’re going through is highly present. The more your first-order response is retreat and denial, the more your second-order responses will be some sort of fearful, overall reactionary retreat. There’s a reason most approaches to re-enchantment have a reactionary or anarcho-primitivist flavor. The challenge isn’t to find new modes of post-Covid meaning-making. Any idiot can find a retreat LARP that fits. The challenge is to have those modes be future-positive, optimistic, curious, compassionate, and still interested and involved in the grander human story.

In a way, an article of faith for me is that the courage to be present in the moment when things are difficult actually lessens the total amount of courage you’ll need to get through the rest of your life, including the delayed effects of tough times. I an actually much less courageous than most people. I just tend to think in terms of the NPV of courage needed through all of life, not just the courage called for in the moment.

If your response to Covid has been to retreat from social media and move to a farm where you live a primitive, fearful life, in my book, you’ve kinda failed to rise to the challenge of this historical moment. You’ve given up on true re-enchantment and settled for a fearful nostalgia instead.

Equally, if you yield to the collective euphoria that’s coming by diving in and partying like crazy, that’s actually just the flip side of waldenponding. It would be equally a failure.

So yes, I do think the “plague is a major bell-bottom bummer” (I’ve never heard that phrase, but it’s a good one), but I’m pretty happy with how I am responding to it, both practically and in terms of managing my psyche through it. I’ve gonzoed my way through it and will continue to do so.

~~~~~

So that’s it for this special AMA edition of the Art of Gig. 5 more issues to go before we wrap!

Note: If you are forwarded this newsletter, please be aware that it will be shutting down on April 30th, 2021, and the archives published as an eBook. So if you’re interested in subscribing, I recommend waiting for the eBook instead. If you do subscribe, please use the monthly option, not the annual one, to save me trouble wrangling the refunds.