With this issue, we conclude our 5-part series on leaping into the gig economy, and put it all together with a preparation roadmap. This part can be read stand-alone, though you’ll get a lot more out of it if you’ve been following the whole series.

Timing the Leap

Based on everything I’ve said so far in this series, about the first leap, leap risk, minimum viable cunning, and the inner game of gigwork, you might be tempted to conclude you should look at the preparation work you have to do, and then plan to leap in N years, where N is a function of how much preparation you think you need.

No. This is exactly backwards. It’s Soviet 5-year plan thinking. It’s corporate employee “career ladder” thinking. You’re not trying to “put in the time” to “earn” a desirable title or position like a corporate lifer. You’re trying to craft an escape to free agency.

Illogical though it might sound, you have to pick a date or leap event (such as a certain critical meeting going a certain way), and then do the best job of preparation you can before that. The rest will have to be done under live-fire conditions after the leap.

Why?

Because preparedness is actually the least important of 4 major factors that should influence the timing. It just happens to be the one you have most control over.

The factors driving the timing of your leap are: Preparedness, Risk Appetite, Opportunity, and Depressors. You can remember this with the convenient acronym PROD.

-

Preparedness is actually the least important of the four, but the only one you can actually do something about. So there is a temptation to let it drive the timing exclusively. I’ve written 4 posts about preparation, but that doesn’t mean it’s the most important factor in timing. I was very well-prepared personally, but that’s just because my preparation needs happened to line up well with the right timing.

-

Risk appetite, in my experience, does not change much for people, barring seriously traumatic events (which in most cases reduces risk appetite rather than increasing it). But while you can’t change this, you can “trick” your risk appetite in ways I’ll outline in the next section. I’m personally very risk averse in terms of financial and entrepreneurial risk, so I had to trick myself quite strongly.

-

Opportunity is the second most important factor, but the one least within your control. Y2K was a good example. It launched many companies and careers within a tight launch window. You can create small, local opportunities around yourself by taking the initiative, but the biggest tailwinds will generally be in the environment. You have to be alive to them. My opportunity was of course, the brief window of opportunity when blogs ruled the internet.

-

Depressors are the single most important factor. If you are in a situation you hate, doing work you dislike, with people you detest, in an industry you think is toxic and dying, everyday life becomes a special kind of hell, and you die a little more ever day you stay there. If this applies to you (fortunately, it didn’t apply to me), leap as soon as humanly possible, before you get reduced to subhuman gloom, and there’s not enough of you left to save.

So remember the acronym PROD: preparedness, risk appetite, opportunity, depressors. We’ve talked a lot about the first element in this series.

The last two are very situation specific, so I don’t have much to say about the opportunities and depressors in your specific environment. If I had the bandwidth to offer 1:1 coaching, which I don’t, this is what I’d spend a lot of time on. But if you can find a friendly neighborhood gigworker who has already made the leap, you may want to seek out mentorship from them on opportunities and depressors.

The second element, risk-appetite, is something we can say a few general things about.

Hacking Risk Appetite

PROD gets at the logical, analytical side of timing the leap, but there’s also a gut-level intuitive side to the timing, which involves hacking your risk appetite to accept the right level of risk rather than imposing the level of risk it is comfortable with on your conscious thought. Yeah, this is a mind-over-gut programming operation. Like messing with your gut microbiome with weird supplements, except via memetic microfauna that live there.

And you must hack your risk appetite, otherwise it will trigger harmful stress responses that prevent you from managing the eminently manageable risks. You don’t want to thrash and drown in 2 feet of water simply because you can’t swim. Controlling your panic response will reveal the solution to be very simple: you don’t need to learn to swim in 5 minutes. You just need to stand up.

There’s two versions of risk-appetite hacking problems. Too much risk appetite (uncommon), and too little (much more common).

Generally, too much risk appetite leads to leaping too early, and too little leads to leaping too late. But occasionally you see the reverse. Too much risk appetite leading to waiting too long (for the “big score” opportunity) and too little leading to leaping too early (because there’s a less scary thing you can do now that’s easier than waiting for the window of opportunity to do the more scary thing).

But you don’t want to be too early or too late. You want to time it just right. Don’t underestimate the deep sense of power that comes from feeling in your gut that you’re leaping at the right moment. Here’s a famous dose of Shakespeare you should commit to memory:

There is a tide in the affairs of men.

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such a full sea are we now afloat,

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

The more time you have available, the more (and more effectively) you can prepare — up to a point. Beyond that point, more preparation is actually fear. It might be valuable, but the value will be lower than the opportunity cost in missed opportunities, toll exacted by continuing in depressing situations, and not hacking your gut to take better risks. Here’s a second dose of Shakespeare you should commit to memory:

…Art thou afeard

To be the same in thine own act and valor

As thou art in desire? Wouldst thou have that

Which thou esteem’st the ornament of life,

And live a coward in thine own esteem,

Letting “I dare not” wait upon “I would, ”

Like the poor cat i’ th’ adage?

These two verses, interestingly, are spoken by Brutus and Lady Macbeth, the villains of Julius Caesar and Macbeth respectively. The kind of boldness it takes to navigate your first leap is actually the same kind of boldness it takes to commit murder. Except in this case, the victim is your old low-agency, unhappy self, rather than another person. You’ll still be unhappy (happiness is overrated), but it will be an interesting new kind of high-agency unhappiness that you’ll actually enjoy mastering. If only because you’ll only have yourself to blame with pointy-haired bosses and toxic coworkers out of the equation.

Your first leap is an ego death triggered by out-of-comfort-zone risk-taking, followed by regeneration into a fuller life. You know in your gut you must leap, because to not do so would be to resign yourself to a slow death.

Once you’ve truly committed in your gut, you will find that waiting is almost intolerable, and you will naturally, try to advance the timing. The risk of mistiming the leap will shift polarity. Where you previously risked procrastinating till its too late, you will now risk leaping too soon because the stress of waiting is too much (kinda like how nervous soldiers might fire before “seeing the whites of their eyes”). Shakespeare one more time, again from Julius Caesar.

Between the acting of a dreadful thing

And the first motion, all the interim is

Like a phantasm or a hideous dream.

The genius and the mortal instruments

Are then in council, and the state of a man,

Like to a little kingdom, suffers then

The nature of an insurrection.

The point of developing an awareness of this gut-level aspect is not to change your risk appetite, but to hack it. That element of PROD, like I said, is not easy to change. The point is to develop your capacity to leap despite the risk being outside your tolerance range, and the prospect of fear being greater than you think you can handle.

Hacking risk appetite so you take on the right level of risk, rather than the level that feels comfortable, is a bit like dieting. You have to commit irreversibly to a risk level before the actual fear kicks in, and then short-circuit the ability of your appetite to do anything about it.

It’s like deciding to eat a salad for lunch, and locking in that commitment by throwing away the cake and chips.

Caesar burning bridges and Cortez burning boats are among many famous examples of leaders hacking risk appetite, but you have to go beyond resonating with such allegories to crafting literal irreversible commitment moves for yourself.

In my case, a big part of hacking my risk appetite was getting very small cash-flows going. They were barely better than nothing in terms of actually sustaining my life financially, but they made a huge difference psychologically, as proof that I could make money flow without help from an employer. Apparently my gut can’t count, and doesn’t know the difference between $100 and $1000. I exploited that.

How do you know when you’ve hacked your risk appetite into submission?

You’ve heard how entrepreneurs have to go from a logical Ready, Aim, Fire to an illogical Ready, Fire, Aim operating condition. Hacking risk appetite takes the illogic one step further. Your first leap is almost certainly going to be a case of Fire, Aim, Ready.

If you’ve hacked your risk appetite right, and worked on PROD as much as you can, it should feel like you’re making the irreversible commitment before you’ve figured out a direction, and picked a direction and started moving before you’re actually ready to sustain movement.

It feels unnatural, but that’s a good (though not definitive) sign you’re doing it right.

Fire, Aim, Ready

So you’ve picked your leap date or event, and it’s N years out, or perhaps it’s in the past: you’ve already leaped, underprepared. But no matter what N is for you, it’s likely going to be a fire-aim-ready script.

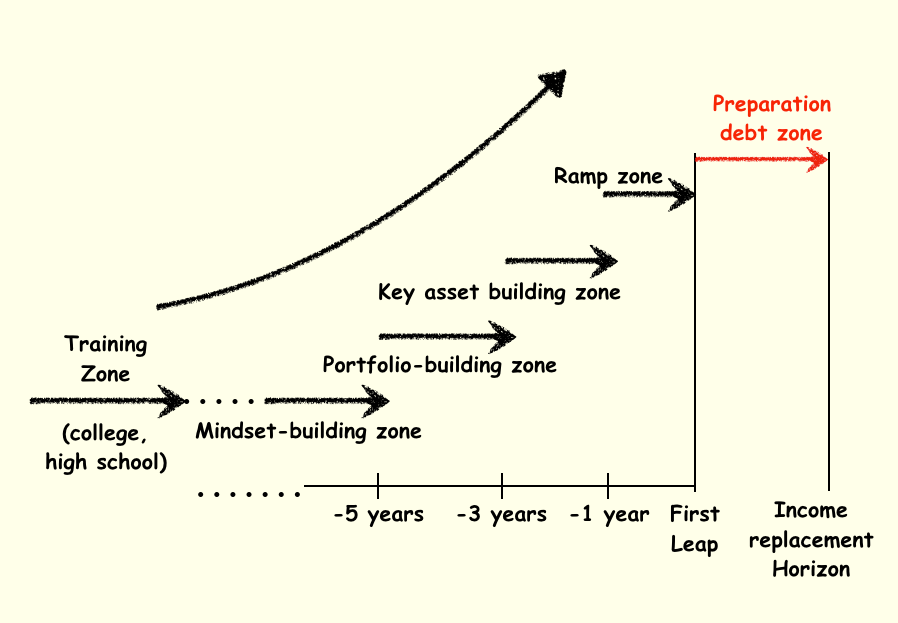

The question now is, how much preparation can you cram into what time you have between fire and ready (which is possibly negative). Here’s a rough breakdown, illustrated in the drawing.

N < 0: You’re in preparation debt zone. You’ve leaped and are not ready. Get active on Twitter. Create an interesting deck around a topic of expertise, and see if you can line up talks at meetups and conferences (simply attending and “networking” is very low value). Make money by any means possible. Drive Lyft. Get a low-status temp job that seems beneath you if you must (but commit to quitting asap). Save money by any means possible, borrow if you must (and can). N<0 is an emergency response regime, and you will do most of this naturally because it is obvious. Your actions aren’t going to be very leveraged or strategic. You’re in band-aid territory. But getting out of the emergency state is less obvious and natural. It is surprisingly easy to adapt to, and stay in, this crappy temporizing zone far longer than you should. Your goal here is to start aggressively buying time so you can actually catch up on preparation work that should have been done before the leap. Preparation debt is not a good state to be in, and your survival chances are weakest, but it’s not necessarily fatal. And it can be a better state to be in than in a soul-killing job.

0 < P < 1: You’re in launch ramp zone. Count the number of friends outside your work you interact with regularly outside of work, and increase that. They will be more valuable in the short term than shallow “networking” contacts or current at-work colleagues (who may feel betrayed and not inclined to help when you leave). Double or triple your investment in outside high-frequency friendships. If you’re in a line of work that allows for creating outside-of-work artifacts, identify a small warm-up pregig, like a pro bono project for a nonprofit, a contribution to an open source project. And most importantly, ramp up your performance at work. Exiting on a high note rather than as a lame duck creates a LOT of positive externalities. And of course, start saving aggressively, on a war footing.

1 < P < 3: You’re in asset-building zone. Between 1 and 3 years, you have enough time to build a meaningful asset like a blog, email newsletter, book, or side project from a cold start. Not only should you build an asset, you should have turned it on at a test level, and had some validated success with it. Also: get on a steady savings ramp. Not in an illiquid form like a retirement account or a house, but in a form that can be rapidly liquidated. And these savings have to be above and beyond emergency savings (which for most employed people tends to be 1-3 months, so think in terms of 6 months out).

3 < P < 5: You’re in portfolio-building zone. Between 3 and 5 years, you have enough time to build more than one asset. When I jumped ship, I had been developing the option for 4 years. Besides my main blog, ribbonfarm, I had a book almost ready to go, and a strong following on Quora. Try and make these different kinds of realizable options. A book, once launched (especially if self-published) can instantly create a spike of revenue. In this planning range, your savings behavior still has to be slightly different (more loaded on liquid assets than people who intend to stay employed)

5 < years: Beyond 5 years, we are in mindset-preparedness zone. The behaviors include: reading outside your sector, reading management and self-management books, and approaching your job with a very different mindset than the people who expect to stay in paycheck employment their whole careers. Preparing for the option of leaping into the gig economy might actually make you better at your job, ironically (it serves as a BATNA that increases your risk-taking at your job, leading to better results since most employees take too little internal risk).

Training Zone: If you’re in college or high-school, and the clock hasn’t started ticking yet, you’re in the training zone. If you’re aware that the future is giggy, you will approach your educational options differently, try and learn different skills than if you were preparing for a paycheck career in a series of jobs.

Contrarian view: if you’re in education, I don’t think it’s a good idea to dive right into the gig economy. If you can, spend some time in a paycheck world while it still exists. Gig work still uses all the same skills as paycheck work, so you might as well learn those skills on someone else’s dime.

In Conclusion

Here’s the big boring secret about the gig economy. Though it is still a small fraction of the labor market (I’d estimate about 20-25% in the US), everybody is likely to cycle through it at some point, at least for a while. So there’s nothing particularly special about being in the gig economy. The difference isn’t between people who are/will be in it versus not, but between people who are happier in it versus not.

Yet almost nobody prepares for it, intellectually, financially, emotionally, or educationally. Weird, huh?

But despite the fact that it will touch almost everybody’s life in the future, it is somewhat magical: the gig economy exists only to the extent you believe in it. It is like an economic equivalent of the Room of Requirement in Harry Potter. You have to kinda believe it is out there and that it will appear around you when you need it.

Actually, the paycheck employment economy also only exists because we believe in it enough to jump into it, without guarantees or certainties that there’s a there there for us to land when we head out interviewing.

The only difference is that the paycheck economy comes with a lot of highly visible social proof props called “companies” that make belief easier, by building a concrete landscape of offices with reception desks, equipment, badges, and uniforms. Believing in the paycheck economy is like suspending disbelief enough to watch a movie. Believing in the gig economy is like suspending disbelief enough to read a book. You have to construct your own mental imagery to make it real.

All economics is self-fulfilling prophecies. Stuff that happens because people believe it can. When an economic sector dries up, all of it can turn into a ghost town overnight. Whether it is populated by gig-workers in cafes, or employees with badges in offices, makes no difference. The cafes empty out and close down. The offices empty out and close down. For Sale signs go up. Tumbleweed blows in the wind. Zombies appear and stagger about.

Gigwork or paycheck work, we all live in the same economy. The only difference is how we manage our exposure to the risks of living inside the collective fictions of economic modernity, sustained by the circulation of these little green fictions we call money.

To leap into the gig economy is to leap into a state of belief that does not require all the props. It is a state of belief that draws directly from the raw, collective élan vital of homo economicus, trusting in your fellow human beings to create the demand for whatever it is you might be capable of supplying. It is the opposite of a fuck-you-money flouncing out of the economy. It is something like a trust fall into the waiting hands of unknown people who you are going to believe in, and who are going to believe in you, so you can invent your own future.

And that’s it for our extended look at your first leap.

We’ll switch gears next week to a different focus, heading into winter.