The idea I’ve cited most often in the last few years is Arthur C. Clarke’s “hazards of prophecy” in Profiles of the Future, which asserts that the failure of nerve is a bigger problem than a failure of the imagination. Failure of nerve happens when, despite being given all the facts, and despite the required reasoning being trivial, people fail to draw obvious conclusions about the future. The problem is that the simple reasoning from simple premises leads you towards an unpleasant conclusion that’s hard to face.

This is an important phenomenon for us in the gig economy to recognize. Possibly the most basic level of failure in failed gig economy careers is failure of nerve.

First Leap versus nth Leap

It’s sort of obvious that taking your first leap into the gig economy, especially when you’re not being forced to by circumstances, is an act of courage. In large part though, the courage required there is a kind of dutch courage, except that you’re high on the prospect of freedom rather than alcohol. You don’t actually know much yet about the perils you’re diving into, or what kind of courage you will need, as you plan your first leap (see my 5-part series on that). You’re merely assuming you have it.

The courage it takes is based on a belief similar to “I’m smart enough to graduate college” or “I’m strong enough to lift this weight.” It’s a belief that allows you to try, but it may not be enough for you to succeed. It is a belief that you will have the courage necessary when it is actually called for.

These beliefs fuel a kind of Dunning-Kruger false confidence that relies on ignorance, but can bootstrap you into the real thing. You find out how you actually stack up as tests of such beliefs hit you one after the other. By the time you’re on your nth leap, your courage is real, because it is in response to dangers you do understand.

Training Nerves versus Mitigating Risks

Like intelligence or strength, courage is an attribute that can be trained, refined, specialized, and generally matured into a knowledge-based understanding of what one is actually capable of. As with intelligence and strength, most people are far away from the genetic limit of what they might be capable of.

But training your nerves is not the same thing as reducing the risk itself through risk-mitigating skills.

A good example is the difference between learning to swim and learning to jump off the high board.

Learning to swim takes no courage at all if you do it in the shallow end, under skilled supervision. You can get to swimming safely without ever testing your nerves, or ever having to overcome even a moment of panic, by gradually developing your skills.

On the other hand, assuming you know how to swim, learning to jump (not dive) off the high board takes no skill at all. You just have to step off the board and fall. It’s all about raw nerve. It’s about learning to overcome the fear itself, accepting that knot in your stomach and the sudden rush of weird sensations as you step off. And it’s almost a one-step thing: the second time is far easier, and by the 10th time, you’re actually enjoying the thrill.

Learning to function effectively as a paycheck employee does not take much nerve, but does take a lot of specialized employer-specific skills you can learn in the shallow end of the pool. If the organization is well run, it should be like learning to swim with a good teacher. If it isn’t, you’ll drown.

Learning to function effectively as a free agent, on the other hand, takes a lot more nerve, but generally no additional skills beyond what you already have. It’s like learning to jump off the high board repeatedly till you enjoy rather than dread it.

To the extent there are risks, you don’t actually mitigate them much. You just learn to deal with the consequences of environments with unmanaged, unmitigated risks.

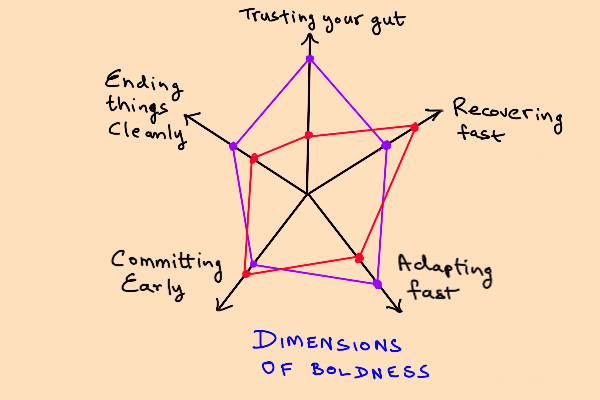

Dimensions of Boldness

Though you can’t train your nerves in the same way you train skills that derisk an activity, you can train them. What you’re learning is to act in certain ways despite unpleasant situational responses getting in the way.

It helps to break it down a bit into aspects. Here’s a spider chart of the “nerves” I think matter most in the gig economy. The purple polygon is a sketch of what I think my own pattern of boldness looks like. The red one is the pattern I think my buddy Arnie Anscombe, data science consultant, exhibits. Relative to him, I’m bolder about trusting my gut, adapting fast, and ending things cleanly, while he’s bolder at committing early and recovering fast from setbacks.

You should try drawing your own.

Along each spoke, there is a dimension of courage associated with a particular pattern of failure of nerve. In each case, you lose opportunities, time, or both. Lose enough of both, and you lose the plot entirely and bomb out of the gig economy.

-

Failure to trust your gut: when things seem okay on the surface, but there’s a couple of red flags, and something just seems wrong at gut level, you either trust your gut and poke at the red flags to either confirm or allay your suspicions, or you studiously ignore your gut.

-

Failure to recover fast: you will routinely have setbacks with immediate and unpleasant impacts. A gig fails to come through. An invoice gets held up, causing a cash-flow crunch. A sudden medical emergency stresses your reserves. In each case, if your nerve fails, you’ll initially freeze into helpless inaction, wondering why the universe is being so damn unfair to you. The failure of nerve happens when you don’t unfreeze and begin acting again quickly enough.

-

Failure to adapt fast: circumstances have changed. The CEO was replaced, and your champion at a client company, who was going to send a nice juicy gig your way, is suddenly out of power, or out of a job. Do you reorient quickly and do something about it, or wait just long enough that the loss becomes irrecoverable?

-

Failure to commit early: You have an idea you feel is basically ready to be tried. You’ve workshopped it a bit on Twitter. People are excited and seem positively disposed towards it. But you delay and hedge, and don’t act, and when you’re finally ready, the moment of zeitgeist resonance has passed. You’re too late, or someone else gets there first.

-

Failure to end things cleanly: A potential client has been stringing you along for ever. But you don’t cut the conversation short as a waste of time and move on. Or a client who you thought represented 10s of hours a month in billings is only sending 1-2 hours a quarter your way, but demanding a level of support and situation awareness maintenance that you can only justify for much higher volumes. But you’re letting the gig limp along instead of just politely ending it.

All these cases are failures of nerve. The situation is not intricate or hard to read. The outcome on the present course of inaction is obvious and bad. It is obvious what to do instead, to try and make a better outcome happen.

Yet you don’t act.

Failure of nerve.

The horror of recognizing that something isn’t working, or that a comforting belief isn’t true, or that something important has changed.

The good news about failure of nerve is that it cannot become a habit. If your nerve fails you often enough, you’ll just fail entirely and drop out of the gig economy into something else (generally more unpleasant).

What can become a habit is acting with nerve. And that takes no real skill. Just doing the thing that obviously needs doing. And doing it again, and again. Until the panic reaction turns into an exhilaration reaction.

The reason this works is obvious: the riskiest thing you can do is to take no risks at all. Every time you act with courage, and avert a failure of nerve, you rebalance luck in your favor. You start being right more often. You attract more serendipity than zemblanity.

In fact, that’s how you know if you’re acting boldly enough. When you start to feel that you’re getting unreasonably lucky, and more of your bets are paying off than you’d have expected.

The idea that “fortune favors the bold” is not an observation about the nature of divine agency, it is an observation about the interaction of active human agency, luck, and unintended consequences. Fortune appears to favor the bold because the bold are making their own luck by acting in obvious ways in response to obvious imperatives. Failure of nerve is so common, it is almost the default, so even doing marginally better than others pays off.

As Wayne Gretzky succinctly put it, you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.