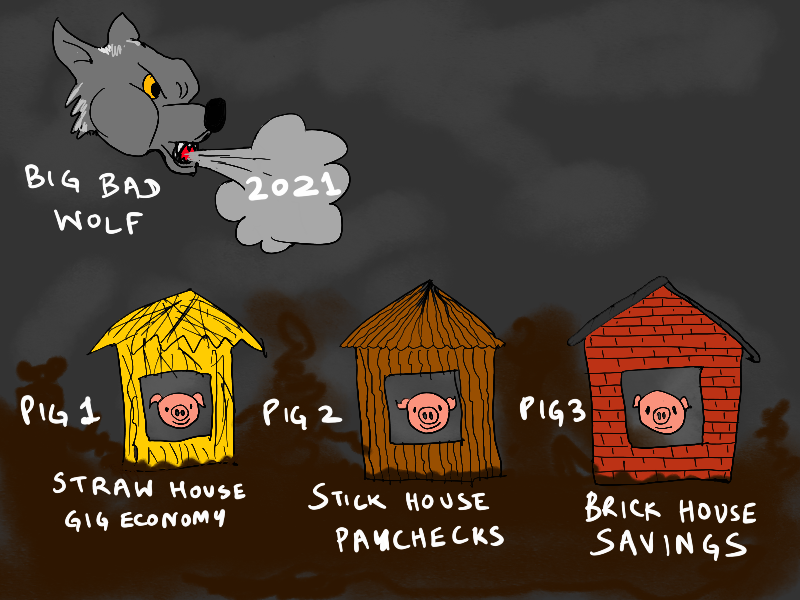

Well it’s only January 7, 2021, and the Big Bad Wolf is already huffing and puffing more powerfully than in 2020, threatening to blow our houses down. There’s an insurrection being held at bay in the United States, a more virulent mutated SARS-CoV-2 abroad, and the vaccination effort is running into a wall of distribution snafus and vaccine hesitancy.

What’s a precarious free-agent to do in this environment? Turns out the folk tale of the Three Little Pigs and the Big Bad Wolf sheds some interesting light on the problem. It is a good allegory for resilience in turbulent times — the Big Bad Wolf huffing and puffing like it’s 2021.

Which of the three little pigs should you try to be: the one in the straw house, the one in the stick house, or the one in the brick house?

-

The pig in the straw house is the typical free agent, with the flimsiest of protections

-

The pig in the stick house is the typical paycheck employee, with a little more apparent resilience

-

The pig in the brick house is the one with a strong liquid cash position and deep savings, whether as a free agent or an employee

Here’s a perhaps counter-intuitive idea: if you can’t live in a brick house, the straw house might actually be a better bet than the stick house.

As I noted in my first Covid-response post on March 12, 2020, Gigging in the Time of Corona, cash, control, and community is the best formula for resilience. If you’re strong on all three fronts, you have a brick house. If you’ve got that, you’re in good shape.

But if you compare paycheck employees with poor reserves to free agents with poor reserves, who comes out on top?

Superficially, it might seem like the stick house is better. It buys you a little extra time against the huffing and puffing of the Big Bad Wolf. That’s good, right?

Maybe not. In 2020, we saw huge numbers of people on paychecks being laid off or furloughed. They were reduced to running up credit card debt, and desperately trying to get through to the unemployment office for weeks and months on end. They had more time, but were less prepared to exploit that time.

On the other hand, the gig economy not only seemed to weather the storms, but even grew, becoming the backstop for people who had lost paycheck jobs.

Paychecks, as many have pointed out, have something of an addictive quality to them. They tempt you into unsafe cash-flow management behaviors through their very predictability. I certainly used to live less safely back when I was on a paycheck.

As an indie, I learned early on that I was in a glut/famine unpredictably cyclic economy. I learned the coping behaviors — build up higher reserves, keep multiple income options alive, and react fast to threats and opportunities. Paycheck people often never learn any of these disciplines.

So when storms hit, they are often caught unprepared. They’re living mindlessly paycheck-to-paycheck (even the well-paid ones; it’s the cost of keeping up with the Joneses), and when the layoff risk suddenly skyrockets — as it did last year — they have no contingency options in place that they can exercise.

Last year, white collar information workers were largely safe, and service workers bore the brunt of the fallout (a double jeopardy of being both more exposed to the pandemic, and to losing their jobs). This year, as longer-term impacts start to kick in, I think the blast radius of 2020-21 will only spread. Nobody is safe in this environment. Not even people celebrating Bitcoin nudging $40,000. Too many things have been disturbed too much.

For paycheck workers in their stick houses, in the cash, control, and community formula for resilience, ALL three elements turn out to be illusions linked to the paycheck.

-

Cash: the paycheck is predictable, but not actually reliable. You could be laid off easily in a crisis. Your employer might simply buckle under the stress.

-

Control: you don’t actually have control over your destiny. Your project, the darling of several VPs, could suddenly get canceled.

-

Community: Sure you have a nice bunch of coworkers, with whom you used to get lunch pre-Covid. But if you lose your job, you’ll lose all of them too.

The last part came as a forceful shock to me when I quit my last job in 2011. I ended up keeping in touch with almost none of my friends from Xerox. I had lunch a couple of times with a couple of old colleagues, but then the entire work social network, which was such a huge part of my life before, just seemed to evaporate into thin air. If I hadn’t had my online life, I’d have become radically isolated overnight.

You don’t realize how fragile the paycheck situation is until you lose it for the first time. That’s what life in the stick house is like.

Life in the straw house, on the other hand, is paradoxically more resilient because it is more precarious. Random cash flow shocks are routine. A hoped-for gig doesn’t materialize. Another doesn’t pay. That invoice is delayed. This “passive” income stream is suddenly broken due to a billing bug.

Keeps you on your toes.

Now, I wouldn’t say I’m personally in a straw house situation right now. I’ve been at this long enough that I’ve actually managed to accumulate enough savings to count as a bit of a brick house. If all my income evaporated overnight, I could last quite a while before I got into real trouble (much longer than I could have back when I was on a paycheck). But I’ve definitely endured many a straw-house year.

To mix metaphors, you could say my house is a barbell house of straw and brick. I’m set up to be highly sensitive to the economic environment, but also have a savings runway.

But one thing I’ve carefully avoided for a decade now is getting reliant on anything that looks like a stick house — a paycheck-like income stream that is just predictable enough to lull you into a false sense of security, but not actually reliable enough to buy you enough time to reorient in a real crisis — once you wake up to it. While I’ve enjoyed bouts of pseudo-paycheck security in the last decade (like the year-long fellowship last year that ended just as Covid hit), I’ve never become reliant on them.

We’re only at the beginning of what promises to be a drawn-out economic crisis around the world. In the United States it is also a socio-political and cultural crisis. You’re going to have to pay careful attention to how your life is set up, what risks you are exposed to, how those risks are shifting week-to-week, month-to-month, and quarter-to-quarter, and how your option set is evolving.

So yes, it’s 2021, the Big Bad Wolf is up to his old 2020 tricks, huffing and puffing, trying to blow our houses down. But humanity has endured far worse, and through periods when almost the entire economy was a gig economy. These are bad times, but not apocalyptic times.

There’s only a small chance this environment will kill you (literally or figuratively, via livelihood destruction), but there’s a good chance it can make you stronger if you’re properly open to it.

We’re all pigs in this kind of environment, but if we build the right kind of house to ride it out in, we don’t have to get slaughtered.