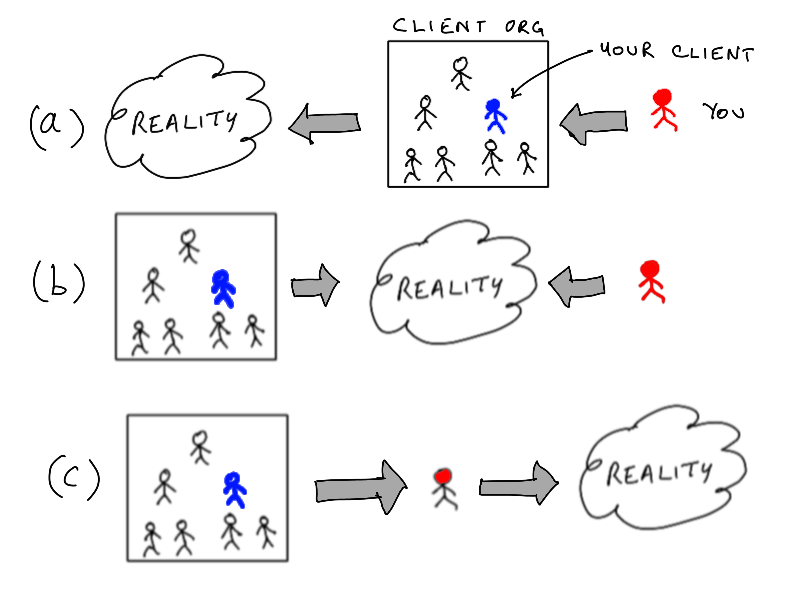

Here’s a question. Which of these three pictures looks right to you? Do you see reality through your client? Do you both look at reality from different sides, or does the client see reality through you?

Trick question! The answer is all of the above and more. Because there isn’t just one salient reality in the picture, but several.

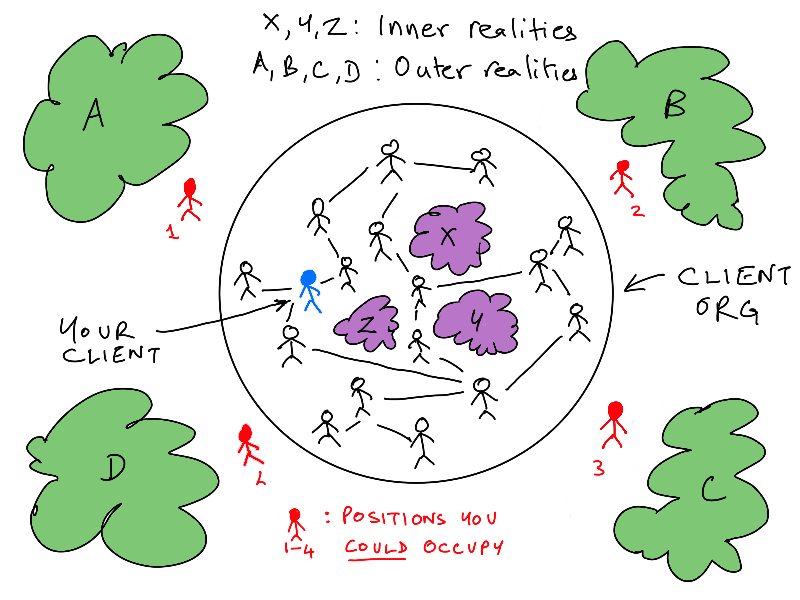

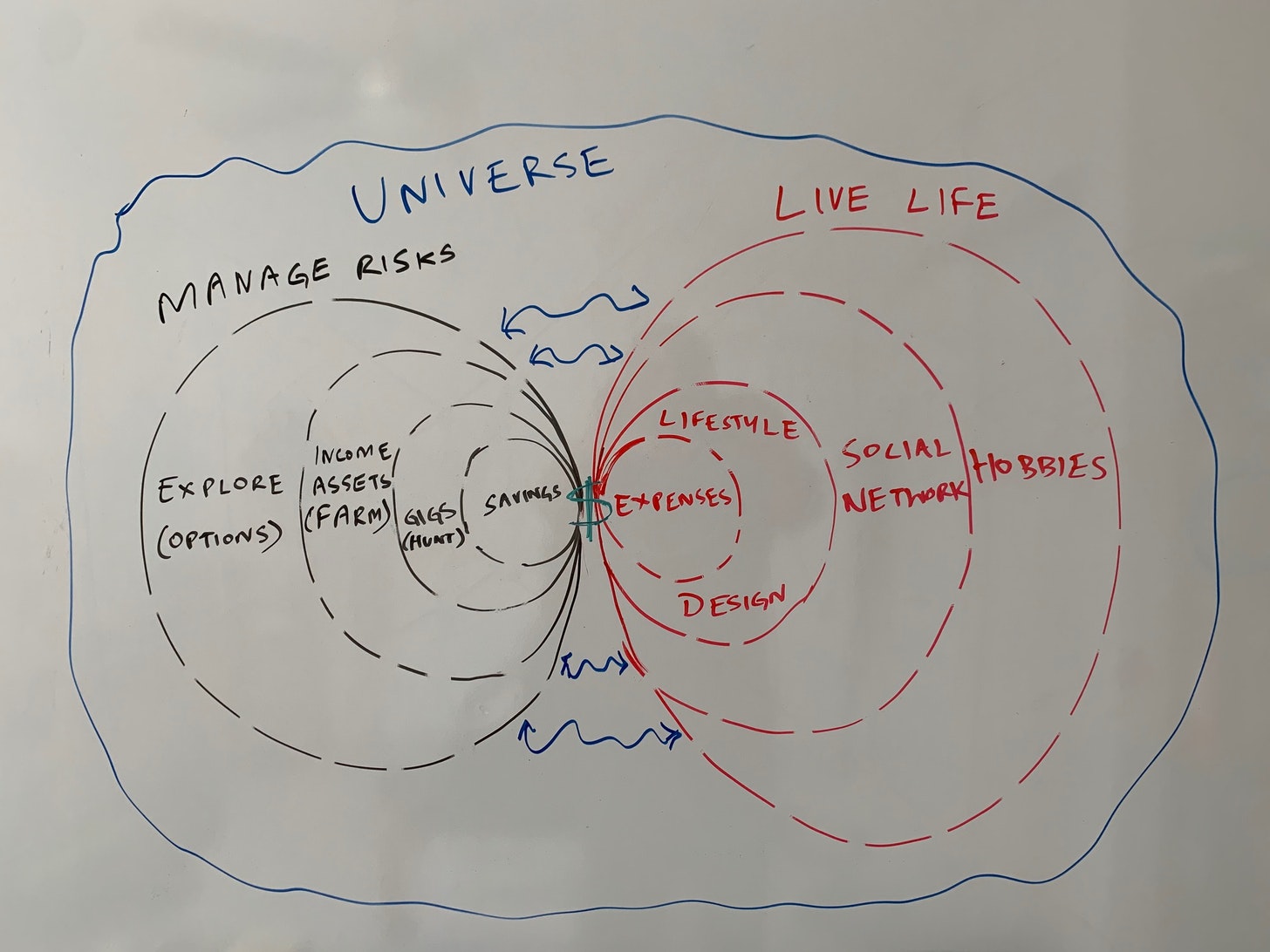

Here is a better view.

Can you spot how each of the 3 cases in the first picture also exists in the second one? The tricky one is (b).

These pictures are the key to solving what I called the dog-fooding problem for indies last week. To understand why, you need to understand a single key heuristic, which I’ll call…

The Reality Proximity Principle: Other things being equal, those closer to a reality will think faster and better about it.

Sometimes one can be too close, and miss forests for trees, but in general, being closer is better.

Consider a typical business with the following 7 relevant realities:

-

X: Reality of how the manufacturing processes work

-

Y: Reality of how long-term b2b customers’ needs evolve

-

Z: Reality of how the culture makes decisions

-

A: Macro trends in the environment

-

B: How a relevant disruptive technology is evolving

-

C: Political/regulatory environment for the sector

-

D: How a competitor is thinking about the market

In this particular case (not in all), as a consultant, you have to see through the client to realities X, Y, and Z. They’re closer. But for realities A, B, C, and D, they might see that reality through you, depending on what position you chose to adopt. In some configurations, you might see different sides of the same reality (like the client and consultant in position 3 with respect to reality Z).

In other words, depending on which reality is salient for a problem or situation, you might be closer to it than they are. For example, many of my clients outside of Silicon Valley have at times relied on me to see Silicon Valley trends and practices better. They’re not interested in me and my ideas as much as the fact that I’m closer to the realities of Silicon Valley than they are while also being closer to their realities than most outsiders.

Now, how is this relevant to the dog-food problem. You may have already spotted the connection: dog-fooding is a behavior based on proximity to an internal reality.

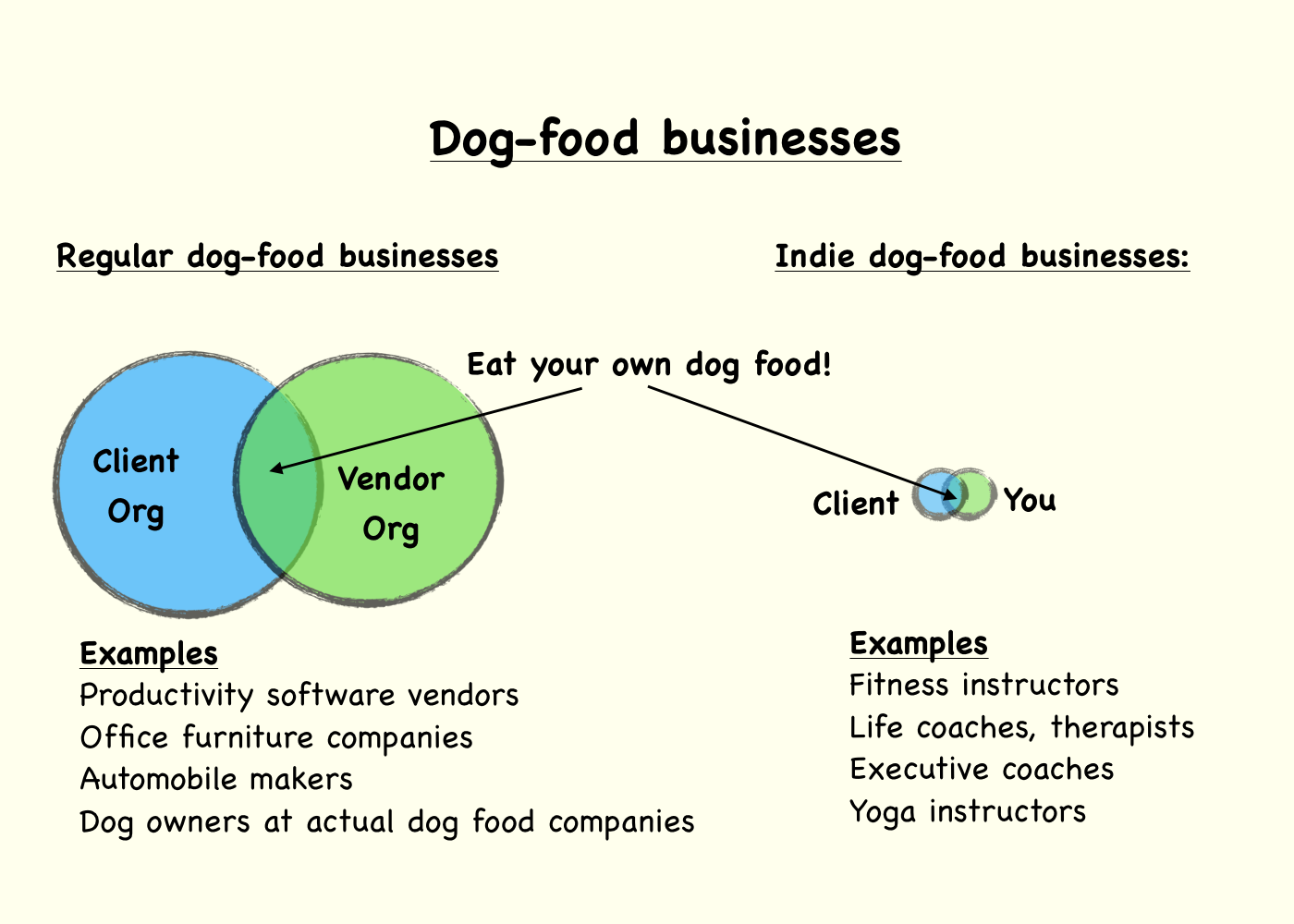

Let’s recap the dog-food problem before talking about how to solve it for indies.

Recap

Last week, I wrote about the dog-fooding problem for indies, which is to apply the dog-food principle to indie consulting practice:

Dog-food principle: When a product or service could be an input for the vendor of that product or service, it should be used by the vendor as an input

Eating your own dog food is good for a variety of reasons: you can iterate faster by being your own lead customer, you create a better marketing perception, and you lower your costs. These advantages are so strong that being able to eat your own dog food is one of the biggest sources of strategic advantage for a business, and a big risk-mitigator for new businesses, including startups and indie consulting practices.

The flip side: all these great benefits only accrue if you are the market leader, or have a decent shot at becoming the market leader. For those already behind, being forced to eat your own dog food is a liability.

Now here’s the problem: as an indie consultant, not only are you very different from a business, you can’t even relate to employees at a human level because you don’t even face the same day-to-day practical problems. So “eating your own dog-food” becomes a hard principle to practice.

Now there’s many specific approaches to solving the problem in particular cases, but I want to share a general formula of sorts for solving it, based on the second picture above: reality arbitrage.

Reality Arbitrage

This might sound obvious, but your biggest advantage as a free agent is that you’re not inside the organization you’re serving. It’s not about who you are, but about where you stand.

This position makes it harder for you to see inner realities. Having to see those through your client creates a bit of a teaching burden on them, which means you start out with a liability even before you’ve proven your value. Why should they bother to help you understand the intricacies of their manufacturing model, or the mindset of their key customers, without knowing what you can do for them better than they can do for themselves?

And what exactly can you, as an individual living an ordinary individual life, do that’s so special?

But being outside their organization means you can get closer to outer realities relevant to their business, while also remaining closer to their inner realities than most outsiders.

This closeness may be some form of literal closeness. Maybe you spend more of your time going to industry conferences than they do, or spend more time tracking academic literature. Maybe you just happen to live in the city where their biggest customer or competitor is based, and you pick up a lot from overhearing routine coffee-shop gossip.

Or it could be psychological. Maybe you can get inside the heads of their competitors better than they can because you don’t share their identity hang-ups.

Don’t underestimate this: the NIH syndrome (Not Invented Here) is very real, and being inside an organization makes you systematically weaker at comprehending certain aspects of outside reality that might be inconvenient, dispiriting, or otherwise unpleasant. Interestingly, dog-fooding itself is the source of many such blindspots.

Whatever it is, the fact that you can be closer to some reality than them puts you in a position to do some reality arbitrage. As an intermediary, you may not understand the outer reality B as well as insiders of B, but you can understand it better than your client can from within their organization. By being closer to the the relevant inner reality X on the other hand, you can also apply the ideas of B better than insiders of B.

It’s basic arbitrage: you’re closer to both than they are to each other.

Reality arbitraging is not the same as dog-fooding, but it is a more than acceptable substitute that delivers many of the same advantages.

Reality Arbitrage vs. Dog Food

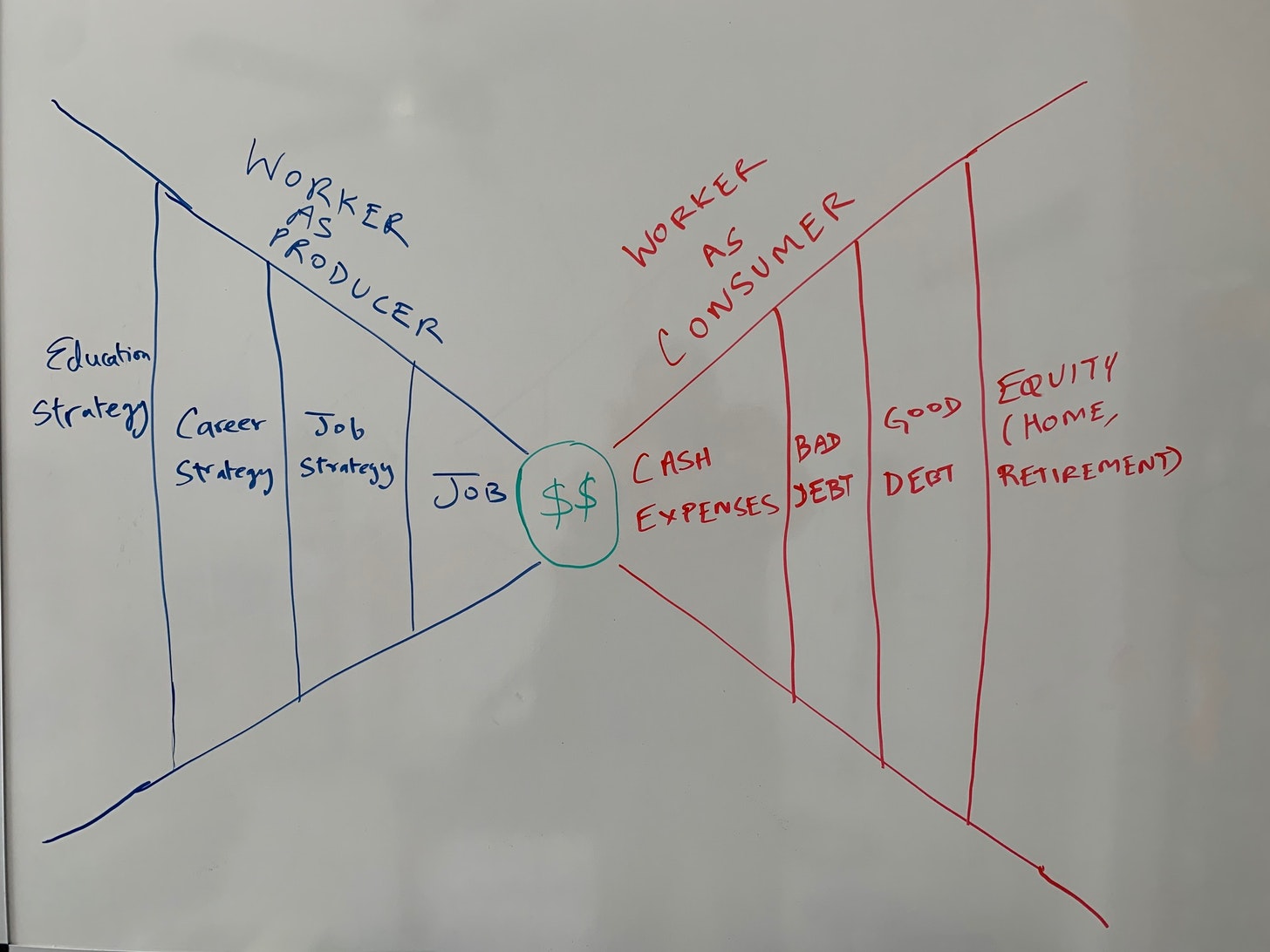

Both reality arbitrage and dog fooding are examples of a broad class of strategic advantages that have to do with being able to iterate and learn faster by being closer to a reality: ie turning the reality-proximity principle into a time advantage.

Dog-fooding is about being turning your natural closeness to yourself into an advantage. Reconsider the 3 benefits I listed in terms of distance-to-oneself:

-

Being your own customer makes you closer to your own needs

-

Your marketing works faster without the moral hazard/principal-agent problems, and this can be considered being closer to your own biases

-

And finally, the cost advantage of dog-fooding makes you closer to your own profitability

Dog-fooding is a special case of a know-thyself strategy. Being closer to your own needs means you eliminate some iterations based on misunderstanding of needs. Being closer to your own biases means you eliminate some iterations based on moral hazard. Being closer to your own profitability means money not used paying someone else’s margins turns into money devoted to speeding up pursuit of your own opportunities.

It’s a great principle for everybody in their personal life too, but your personal life is unlikely to be very relevant to your consulting work. So you have to look elsewhere for a similar structural advantage in time.

Reality arbitrage is that kind of advantage. When you play intermediary, you acquire a speed advantage that’s mostly useless to you personally, and pass it on. You’re a pass-through entity. And the reason you can do this is that as an individual you can occupy positions in the environment that larger entities cannot, and enjoy perspectives that are unavailable to them.

This is an unnatural advantage to exercise, based on extrinsic position rather than intrinsic qualities. For most of us, our own inner realities are the most powerful ones. We are constantly aware of them. The urge is to build an identity around them, locate your advantages within them, and draw on them to provide value to others.

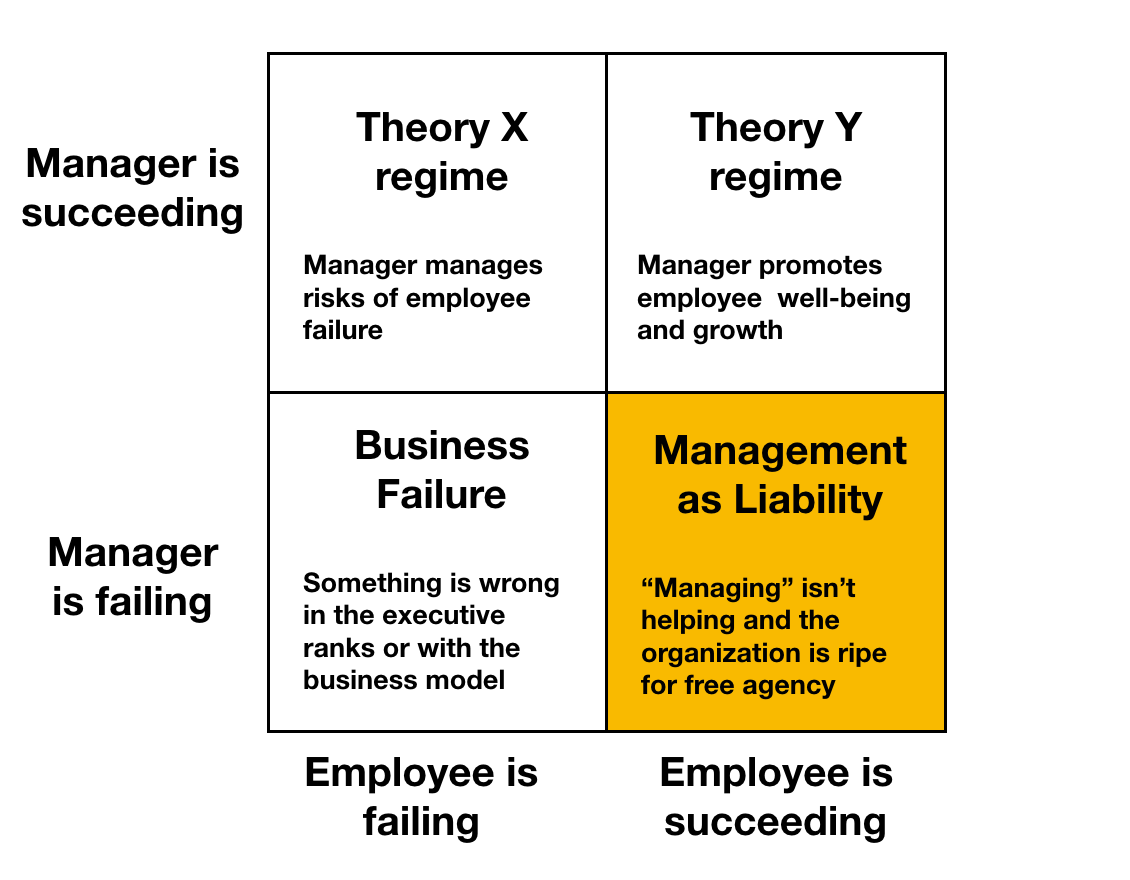

That’s why dog-fooding is not just powerful, it is the default natural source of strategic intuitions. Even more crucially, at the individual human level, to be “seen” by others is to have your inner realities acknowledged and appreciated. It is one of the primary things people look for in a paycheck job after basics like compensation. People take jobs where their inner realities will be most relevant to the inner realities of the company, allowing them to express those realities and be seen.

For consultants though, it is less important to be seen, and more important to be seen through.

In both senses of the world: you are an optical instrument that enhances the vision of another, and your motives are transparent and easy to factor in. Just like a good optical instrument should have easy-to-correct aberrations and flaws.

This explanation is perhaps a bit awkward, but it’s a hard point to explain, or see early on in your indie career. Quitting a job and going indie is so much about listening to your inner realities that systematically deprecating the importance of those realities in favor of a different one can feel hard. Suspending the need to be “seen” can be actively painful, especially if you felt appreciated at your last job.

But consultants do best when they keep their identities small (Paul Graham had a good essay about that).

Examples

The most obvious example of reality arbitrage is of course playing “chess postman” of sorts: picking up tricks watching one client, and putting them to work on behalf of another. There’s a broad class of such tricks that you can safely transmit without fear of falling afoul of NDAs on either side.

For example, if one client runs meetings based on pure opinion-sharing, and another has a workplace norm that all meetings should begin with some data sharing, you can suggest data-driven meetings to the former where appropriate. You can say something like “I’ve seen some of my other clients use this data-driven meeting model and it works well for situations like this.”

Note what you’re doing here: you’re not testifying to your own experiences, or asking to be seen and valued for who you are. You’re not saying “I run my meetings this way” (which would be dog-fooding). You’re testifying as a credible witness to others’ experiences.

Another example is keeping up with macro trends. There’s a reason this is one of the bread-and-butter things consultants tend to offer. It is easier for consultants to stay on top of trends not because they have special access to information (especially for trends which are mostly playing out in public via media reports), but because they can get closer to them.

If you’re the Vice-President of Widgetry at BigCorp, you carry a gravity field wherever you go, and you’ll alter conversations wherever you go. But if you’re an unaffiliated nobody, you can participate in relevant conversations and learn a lot more. People will be more candid with you.

There are many other examples of external realities that you can help intermediate for clients. The key to all of them is to locate a valuable reality that you can get closer to than your clients can, for whatever reason.

In my case, a big one is simply staying on top of management trends and practices. Not by reading the latest airport bestseller, but by simply talking to a wider variety of people, and having a good handle on what’s actually being tried, and what’s actually working vs. not. Very few things covered by airport bestsellers are about actual management trends. Most are about things the authors wish would become management trends.

This is one reason I almost never make up my own management frameworks. I simply work with whatever is around and catching on. The moment you make up your own framework and start trying to sell it, you’re no longer really a consultant. You’re an entrepreneur selling a product. You’re not just at an advantageous viewing point, you have a point of view. You don’t just have perspectives, you have opinions.

You’ve expanded your personality and made your inner realities potentially relevant to others.

This is not a bad thing. It’s just a different thing. One that allows for dog-fooding as it happens: if you’re shilling a System X, you’d better be applying it to your own work and life somehow.

Maybe it’s just me, but I think there’s a certain deep pleasure to be found in resisting the temptation to do that. In working purely as a transparent intermediary of larger environmental forces around you, without trying to put your own dent in the universe. It is one of the existential pleasures of indie consulting. One that inventing and selling your own dog food ruins at least a little bit.

They say about the wilderness: take only pictures, leave only footprints. The indie consultant is the wilderness explorer of the economy. There is something rather poetic about taking pictures in some realities and leaving transient footprints in others.