In my September 19th post, The Price of Freedom, I wrote:

When you give up integrity of methods (in terms of skilled discipline and/or ethics) you break the feedback loop of mindful practice and growth that keeps your cognitive abilities and procedural-ethical judgments strong and growing. So you experience cognitive decline.

I want to revisit this point a bit, in light of recent “news” about McKinsey. For those not keeping up, Pro Publica, the non-profit journalism outfit, along with the NYT, co-published a major feature about McKinsey’s work with the Trump administration on ICE (the US immigration police for those not in the US).

My scare quotes are because these “revelations” aren’t really news, in the sense of being even remotely surprising, to anyone who knows how the consulting industry works. So what is actually news is that this counts as news for the broader public.

The interesting question for me is: what exactly does the general public think firms like McKinsey do, that this counts as news?

That they work this way, and are not too picky about who they work for, is not exactly a secret. So it is unclear what illusions, held by whom, are being shattered here.

The question is important for us in the indie consulting world. In many ways McKinsey is something of a bellwether for perceptions of consulting in general, including the indie and boutique varieties. So the fates of the two sectors are coupled, and shifts in sectoral perceptions matter to us.

The big difference is that the kinds of incentives and pressures firms like McKinsey navigate as a company, you and I navigate as individuals (albeit at a much smaller scale). This means the mindfulness feedback loop I refer to above is much easier for us to maintain in a healthy state. It is also much harder for us to ignore problems with the feedback loop.

For big consulting firms like McKinsey, much of the responsibility for big decisions rests with senior partners, rather than with the rank-and-file who do much of the grinding on engagements, so the feedback loop is vulnerable to being broken.

As independent consultants, you and I cannot blame senior partners for poor judgment, or rank-and-file grinders for failures in execution. We are responsible for both judgment and execution. If the feedback loop breaks, it’s our own fault. If we are held accountable for behaviors of clients we are complicit in, our options for deflecting the blame are limited.

So it is worth understanding what’s happened at McKinsey, and using it as a lens for examining your approach (implicit or explicit, tested or untested) to ethics in gig work. Because believe me, if you last, your ethical commitments will in fact be tested under live fire. It’s not abstract.

Knives Out

The latest news is yet another chapter in almost a decade of bad optics and brand tarnishing for McKinsey and its ilk. It started in 2012 with the conviction of then-CEO of McKinsey Rajat Gupta for insider trading, and the spotlight on Bain thanks to the presidential bid of Matt Romney. It was followed more recently by a harsh media spotlight on McKinsey for its work with the Saudi Arabia. And now this.

Perceptions of the big-firm consulting sector in 2019 are now a far cry from the high regard it enjoyed as recently as a decade ago, though students in MBA programs appear not to have caught on yet.

The reaction to this latest chapter has been swift and harsh. Matt Stoller has a scathing indictment. Louis Hyman, a historian of capitalism at the Cornell School of Industrial and Labor Relations has a twitter thread blaming McKinsey (somewhat unfairly) for inventing the modern, precarious gig economy. Others are gleefully jumping in with whatever pent-up hostilities towards the sector they’ve been harboring.

The knives are out in earnest.

None of this is news of course, which is why many of us are puzzled. Nobody ever pretended the Big 3 consulting firms were not what these sensational “revelations” are showing them unambiguously to be.

What has changed is the public mood in relation to elite institutions, and what Walter Kiechel called the literary-industrial complex, which includes, (besides prestigious consulting firms), elite universities, labs and research centers like the MIT Media lab, business book publishing, and events like TED and Davos.

The mood has shifted from tolerant and indulgent to harsh and unforgiving. It is not a good time to be affiliated with the literary industrial complex if you care about perceptions.

In 1999, the Mike Judge comedy Office Space portrayed consultants as unprincipled sociopaths, but still people to be regarded more sympathetically than the clueless fat-cat executives and managers they supported. People who genuinely relished the intellectual challenge of whipping a struggling company back into shape, and who did meaningful, if not always pleasant, things towards that end. Big Consulting has generally not been regarded as bullshit work. For better or worse, it has been too consequential and self-aware to dismiss with that particular criticism.

So what changed? Why are consulting firms suddenly being held accountable, in the court of public opinion, for the decisions of their clients? Why has the get-out-of-jail-free card stopped working?

Up until the Great Recession, the perception of the Big 3 large-scale consulting industry was largely positive, as cunning rascals you had to grudgingly admire. They were seen as bagmen doing the dirty work bankers and CEOs made necessary. Deliverers of harsh messages. And at their best, pragmatic mercenary foils mitigating missionary tendencies towards ideological excess. They were seen as aware of, and complicit in, high-level governance in all parts of the institutional landscape, but ultimately not primarily responsible for moral matters.

These perceptions matter to us in the indie consulting world because they trickle down to shape how we are perceived as well, which for the most part we’ve welcomed as a positive. In some cases, I’ve made direct reference to them in explaining what I do, as in “I do the same sort of stuff McKinsey does, just on my own, and at a lower price.” It’s not actually a very accurate self-characterization, but it is a convenient starter perception, at least initially, while you establish your actual modes of delivering value.

But these perceptions have changed, and with them, the consequences of positioning yourself relative to the Big 3. The cost of co-marketing convenience has changed.

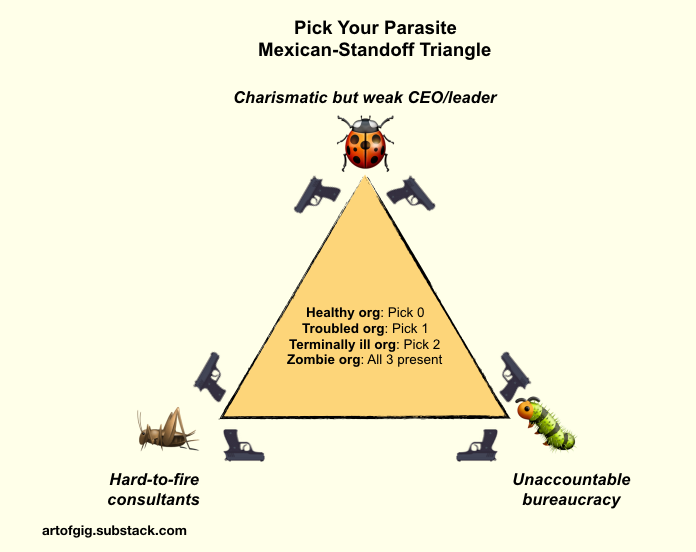

Now, increasingly, the big consulting firms are seen as directly responsible for the moral failures of client organizations. Even perhaps more responsible than client leaders. They are seen as predatory organizations that exploit the general stupidity and incompetence in prey firms to capture them for profit, by making themselves indispensable to running them, but without any accountability for running them well. It’s a cousin of regulatory capture.

And there is some justification there that favors the consulting firms. Many large organizations are so dysfunctional, they effectively have to be run by the big-firm consultants who service them. They are too brain-dead to run themselves unassisted (a condition the big consulting firms had a hand in creating). A good part of the consulting market is a corporate assisted living facility.

But that justification begs the question to some extent. If the organizations are so brain-dead they need to be on consulting-firm life support to function by themselves, it is a little disingenuous to claim that ethics decisions on matters of mission and values are entirely the client’s problem. A generalized zombie is obviously also specifically a moral zombie, incompetent to stand trial.

Who is asking whether the zombie clients should exist at all? Why should such relationships be viewed as anything other than pure scavenging or parasitism in the guise of guardianship?

Turns out, there’s actually an interesting answer here.

Grinder Selection Effects

I’ve been largely sympathetic to McKinsey and its peers through most of my adult working life. Many of my classmates and friends have spent time with McKinsey, Bain or BCG. I actually interviewed with McKinsey in 2003, while finishing up my PhD, but got rejected in the second round. I didn’t mind though. It was so obvious that I did not fit the grinder profile they were recruiting for, it made me respect rather than resent their selection process.

Because that’s the most important thing you have to understand about the Big 3 consulting world: it selects for intelligent, high-energy grinders, not snowflake philosophers driven by foundational curiosities. Tiger Kids if you like. People who set out early in life to win the game as it is presented to them, rather than question, subvert, or change it. Which is not ipso facto a bad thing. If the game presented to such people is a good one, they will play it well, and a good time will be had by all. The world runs on grinders. When it runs at all.

What the critics miss, in their eagerness to call out the unsurprising fact that relatively inexperienced college grads are rented out at a high mark-up (not in itself problematic as far as I am concerned), is just how hard and effectively these people are willing to work, compared to the complacent and comfortable managers at the organizations they serve. I’d be dead in a month if I attempted to work at the pace I’ve seen young Big 3 consultants work. 100 hour weeks are not uncommon. And that lifestyle of constant, stressful travel and living out of hotels takes a toll too. Whatever their sins, taking it easy isn’t one of them. And whatever my virtues, working that hard isn’t one of them.

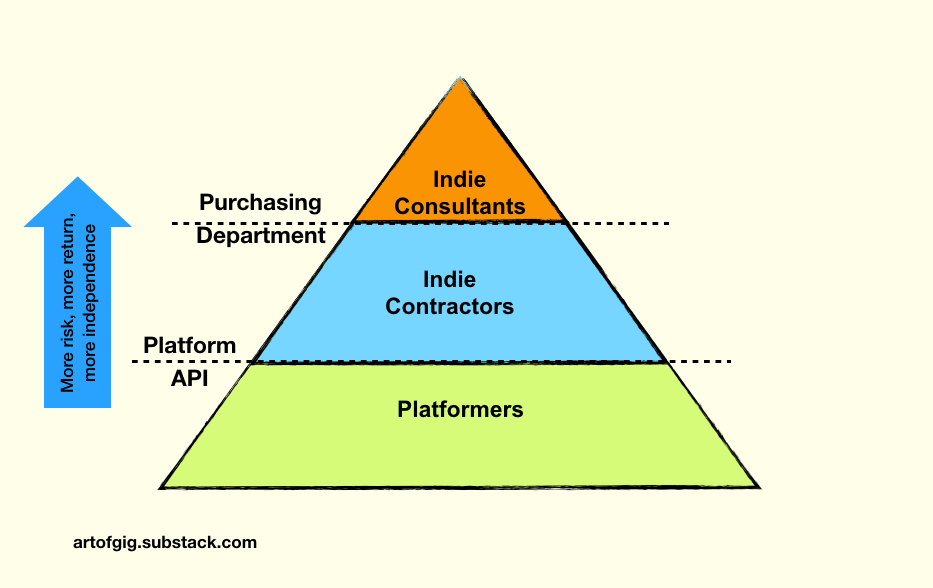

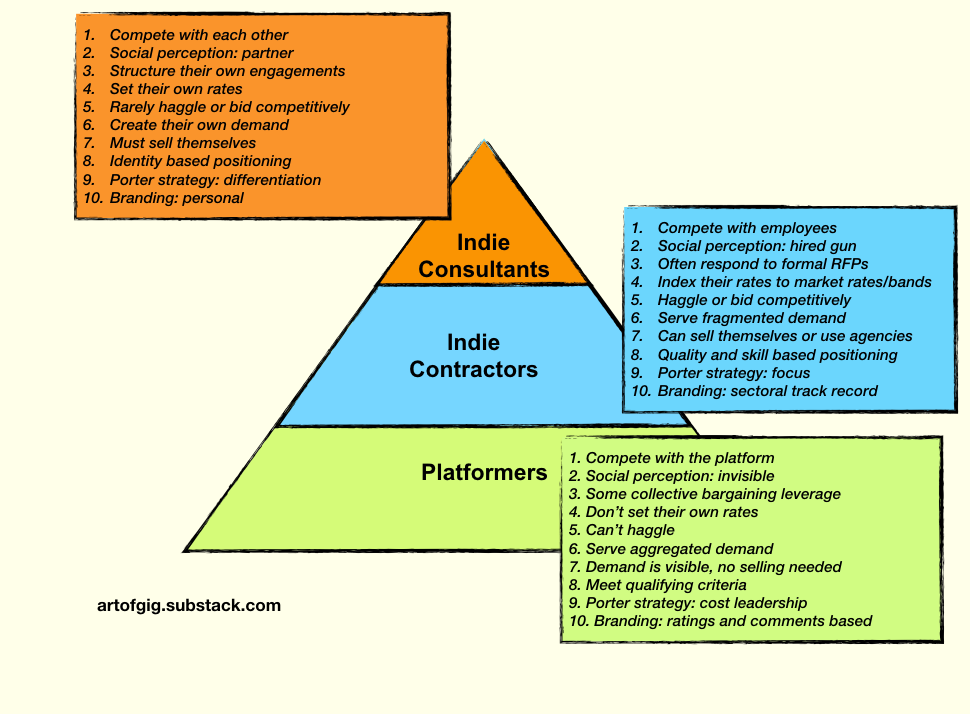

I was clearly not cut out for their approach. Eight years later, when I struck out on my own, that rejection helped me define the kind of consulting I could actually be good at, and could sustainably do at the level of effort I am capable of putting out (which is about 0.1G, where 1G = 1 Grinder). I could position myself in a differentiated way around conversational sparring, and avoid anything that looked like a Big Three 100-hour grind. I could benefit from the perceptions of the consulting industry, but not be bound, limited, or defined by them.

That selection-for-grinders model that dominates the Big 3 world is at once its greatest strength and greatest weakness.

As a strength: there are few forces in the world comparable to the raw mid-grade aggregated intellectual horsepower that can be unleashed on organizational problems by the likes of McKinsey, Bain, and BCG. And it’s easy to underestimate it because what an individual junior associate does can seem like unimpressive grinding. But a dozen such people grinding in the right places can move mountains. Or Fortune 100 companies.

As Matt Stoller notes in his criticism, the problems these firms solve are not exactly difficult, and the advice they end up offering are not exactly breakthrough flashes of genius. But the point is, it does require fairly intelligent grinding at scale to generate that advice with the right numbers and specific details attached.

Finding cost-cutting opportunities in a large corporation is rarely about elegant strategic insight and 2x2s. It is usually an exercise in sending a small army of Excel-armed young associates into every corner of the company, documenting costs, and figuring out where to make cuts by crunching the numbers. And that’s not an activity that trains you much in asking the hard questions about why you’re trying to make cuts in the first place, or why the organization exists in the world, and whether perhaps it should not. Grinding mainly teaches you to grind in more efficient ways.

To be clear, this is work that large companies and organizations are generally not actually capable of doing for themselves. They are too compromised by infighting and self-serving delusions and blindspots. What the big consulting armies are selling is not genius brainpower, stellar imagination, reserves of courage, philosophical insight, or even skilled labor time. They are selling the distance that enables them to look in places internal eyes cannot look, and turns impossible problems into grinds.

At scale.

They are the organizational equivalent of expensive medical imaging equipment. To complain that inexperienced young graduates are being paid big bucks to “run” the playbook is like complaining that medical technicians rather than doctors are operating medical imaging equipment. The value lies in the machine, or in this case, the scalable procedural machine defined by the playbook, not the operators running it.

But as a weakness: selection for grinders is a selection of people with little philosophical interest in matters of principle, impatience with doctrinal thinking, disdain for reflection, and a bias towards hard-driving action.

People with those devalued cognitive strengths within these firms (if they get into these firms in the first place) tend to get sidelined into functional expertise areas where they might write modest little white papers and books that don’t rock the boat, provide occasional injections of spot expertise on special topics, and do thought leadership work, rather than frontline consulting work. Those miscast on the grinder frontlines, or with too much maladaptive talent for the devalued kinds of thinking, tend to burn out early and drop out. They typically don’t last long enough to make partner or execute a smart sideways shift into a VP role on the client side.

So there is a strong adverse selection process at work here. At the tops of these firms, there is not just a disciplined tendency to stay away from doctrinal matters, but a systematic functional weakness in the capacity to think about them in the first place.

The problem with firms like McKinsey isn’t that they aid and abet organizations pursuing unaccountable missions that the broader public might find problematic.

The problem is that grinders aren’t philosophers. Which is not to valorize or demonize either. Just an observation that the two are not the same thing, which is a problem if you believe, as I do, that both have a role to play, and either pretends to be both.

Strategy sans Ethics

The self-labels the Big 3 firms use are interesting and revealing.

All bill themselves “strategy” firms, and “strategy” is a coveted aspirational label for second tier IT and marketing consulting firms eyeing their market from a middle-layer position. The cachet of “strategy” also continues to attract aggressively competitive and ambitious graduates of elite universities determined to grind their way to the top of elite institutional society, and be counted among the movers and shakers of the world at Davos some day, fluidly navigating the top echelons of global power.

But what does “strategy” mean for these firms?

Historically, for McKinsey it has meant being present in boardrooms and C-suites, and participating in decisions at that level, but not getting involved in execution.

For Bain it has meant specializing in shareholder value hacking.

For BCG it has meant brainiac “insights” for framing big moves.

Or as I like to think of it, Gryffindor, Slytherin, and Ravenclaw (Hufflepuffs are the strategy-wannabe second-tier IT and marketing firms).

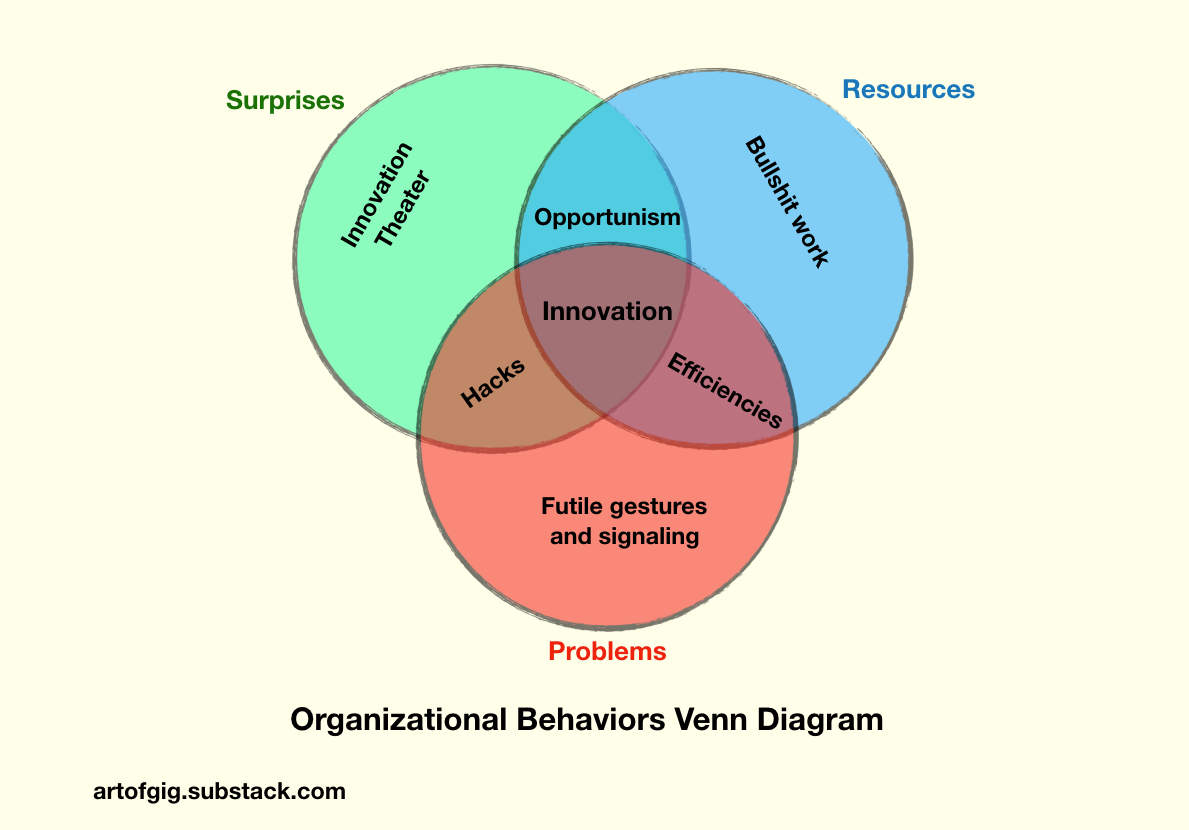

What is missing across the board in this sector is a sense of “strategy” that includes genuine, deeply considered doctrinal, ethical, or philosophical elements (which to me are indispensable components of strategy) driven by real curiosity on those fronts. For the Big 3, those are regarded as the client’s concerns, and decoupled from strategic considerations proper. They are also generally regarded as matters of cosmetics and optics, rather than legitimate concerns worth taking seriously.

And of course, in practice, 90% of top executives don’t want to be holding the ethics and philosophy balls either, and tend to quietly drop it when nobody is looking.

One side-effect of this eschewing of the moral dimension by both C-suite leaders and their prestige-firm consultants is that matters of ethics devolve down to HR and legal departments, whence they are further farmed out to a boutique gig economy cottage industry of what I think of as “ethics grifters”. This is people who gleefully go around creating workshops, training regimens, compliance bureaucracies, and rules around every aspect of individual and corporate behavior. All mostly aimed at creating plausible deniability and cushy jobs for internal ethics czars.

So the cost of abdicating responsibility for the moral dimension at the top is a bloated ethics-grifter bureaucracy in the middle, which has the potential to eventually grow into a cancerous drag that threatens the organization without particularly elevating its ethics game. But that’s a topic I’ll save for another day.

The party line in the consulting world is: the client sets broad objectives based on their CEO values, corporate values, missions, and so forth, and we help figure out how to operationalize it in strategy, by doing the detailed research, creating the justifications necessary, and recommending effective paths.

It is something of a lawyerly stance: the client is something like a defendant in a court of law and it’s the consultant’s job to build the most effective case allowing them to do what they want to do. Passing judgement and doling out punishments and rewards is for juries and judges. For the private sector, that means the court of public and market opinion. For government agencies and politicians, it means the voting public. In any case, it’s not the consultant’s job.

This is a convenient position to take if your goal is to accept the widest range of moneyed clients possible. Work for a dictatorship and a democracy at the same time? No problem, we’ll do both and let the political philosophers work out the meanings. You want to solve for sustainability, profitability, or lowering the cost of incarceration of prisoners or illegal immigrants? No problem, we’ll make you a spreadsheet model for any and all of it, and dig up the numbers necessary to populate it.

It is tempting to conclude that this is an ethically malicious position to adopt out of convenience, and an aspect of the moral hazards of the principal-agent relationship inherent in consulting. Why take responsibility for stuff you don’t have to? There’s clearly no upside.

The real explanation is more sobering: the adverse selection mechanisms by which these firms staff themselves with grinders ensures that the majority of people working in them are genuinely not capable of processing such questions meaningfully.

It’s a cousin of Hanlon’s razor: never attribute to malice what can be adequately explained by unexamined philosophical commitments. In this case, we’re talking about a sort of adversely-selected disinterest in philosophical foundations on the consulting side, and a deliberate abdication of moral responsibilities (accompanied by devolution of the responsibilities to middle-management staff functions) by client leadership.

Either way, the outcome is that the judgement of the court of public opinion, and eventually, the market, is harsh. And when times turn dark, the knives come out.

My own judgment is perhaps less harsh, mostly because I don’t expect anything different from the big consulting industry, and don’t share the illusions that many apparently have (or are conveniently pretending to have) about the sector. They are what they are, and they do what they do.

I don’t have any bright ideas for how the Big consulting companies can change, or whether they even should attempt to do so, since we’re talking about features rather than bugs in their core DNA.

But then, I’m not entirely sure the sector needs to exist at all.

My null hypothesis is that organizations that are zombified enough that they cannot run themselves without Big Consulting support perhaps shouldn’t continue to exist, and deserve to be disrupted and displaced by organizations that can do the necessary thinking on their own (with some modest help from us indie consultants of course 😎). And if the market left over when you eliminate the zombie-life-extension segment isn’t big enough to sustain Big Consulting, perhaps Big Consulting needs to shrink.

To me, ultimately, ethics in consulting is simple: it’s a matter of saying no to things.

Which usually means lowering some topline and bottomline expectations, and being content with less. Ethics are a form of self-imposed taxation. Perhaps you can creatively make up for these tax losses with growth elsewhere, but you can’t magically transform the tax-like nature of the beast. You just have to decide that you believe in the things the taxes pay for, and hope that paying those taxes benefits you in unknown ways in the future. If you knew the actual incentives and payoffs for behaving in “ethical” ways, it would be part of strategy, not ethics.

That’s a decision that’s easy to make as an indie consultant, but quite hard when you’re a huge company staffed by an army of grinders all expecting to climb to the top, and led by people who have been grinding so hard, for so long, they can’t see past grinding as an end in itself to existential questions about themselves or their clients.

They live in a world of TINA assumptions — There is No Alternative. A world of elites that has always been run a certain way, around a set of sacrosanct institutional compromises. A way in which they have an indispensable and well-paid role to play; a role that takes hard work to fill. A role they cannot imagine being fulfilled any other way. If you could imagine a different way, you wouldn’t be working in that world.

We’ll see if they’re right in the next few decades, as the world continues to get eaten by software.

Lessons for Indies

To return to my opening self-quote, the mindfulness feedback loop for staying ethically grounded is much easier for us indies to maintain than for big firms, but it’s not trivial.

The big lesson for independent consultants is that strategy decisions are always also moral decisions. Every client you accept, every task you accept, has both strategic and moral implications for you and the client. And even if you both operate in strictly legal ways, and perfectly within the bounds of the contracts that govern your relationships, you’re still going to be held morally accountable for the work you chose to do.

And as I pointed out in the opening, as an independent, you will never have the luxury of blaming someone else for your choices, the way people in big firms do.

The only excuses that will ever be available to you as an indie consultant, for anything you choose to do, are “I needed the money” and “it was perfectly legal and above-board.” Neither excuse has a history of flying well in the face of hostile public scrutiny.

So doing the right thing is, in the long term, the easiest thing if you’re in the indie consulting world, and want to be able to withstand hostile scrutiny with nothing to apologize for or be ashamed about. You don’t have enough maneuvering room to do anything else. Big firms get themselves into trouble largely because they have the maneuvering room to do so, not because they are morally worse than independent consultants.

This is not abstract theory for me. I’ve said no to potential clients when I’ve been in need of money. I’ve said no to doing specific tasks long-term clients have asked of me. But I’m also no saint. After all, my reputation is based primarily on writings recommending slightly evil sociopathic behaviors. But I’m happy to own that.

The point is, whatever you do, and wherever on the spectrum from absolute saint to absolute sinner you choose to land, you can actually choose to own it in a way big companies generally cannot. So make your choices. Carefully.