Let’s talk about cheats: unfair advantages and cheap tricks that, deployed with imagination and cunning, might mitigate a lot of the unavoidable unmanaged risk of leaping into the gig economy. I call these mechanisms cheats because they are not part of some general theory of systematic risk management. They are situational factors, likely unique to you, for making the leap in a particular place at a particular time. Your cheats come together in your particular pattern of what I call minimum viable cunning.

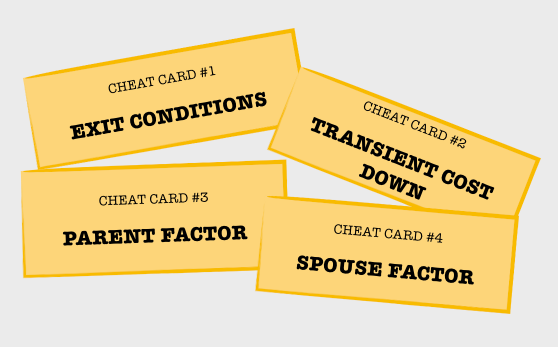

I’m going to discuss 4 common cheat cards that apply to most people, but you can and should think through and identify any uncommon cheats available to you as well.

Let’s recap a bit. We’re now into Part 3 of what promises to be at least a 5-part series on taking your first leap into the gig economy. If you’re already post-first-leap, some of this may be useful for your future leaps. But if it’s all old hat, bear with me. We’ll get back to the non-beginner stuff in a few more weeks.

In the first part, Your First Leap, I set the stage by distinguishing the leap into the gig economy from job searches and entrepreneurial ventures, and identifying common underpreparation mistakes that lead to a lot of people crashing and burning, and returning to the paycheck economy in a weakened state, scarred and scared out of the gig economy for life.

In the second part, Leap Risk, I walked you through an rough estimation process to get a sense of the risk of your leap, and how much of it is unmanaged. Roughly speaking, you can expect about 4 months of ramping to replace every $10,000 (or the equivalent in your country, if you’re not in the US) of fully loaded paycheck income, and optimistically, you can expect to make about half of your income during the ramping phase from gigs. In the example we worked out, a $60,000 annual income led to an estimated 36 months (3 years) of ramping to fully replace with gig-income, and an unmanaged risk estimate of about $100,000 during that period (which you can think of as an income gap you don’t yet know how you’ll fill).

We concluded that you’re unlikely to be able to close the risk gap purely through additional savings because it would take too much time. That’s why you need cheats, cunningly deployed. In fact, even if you could close the gap with money, you probably shouldn’t. Figuring out how to close risk gaps with cunning rather than money is essential early training in gig economy resourcefulness. Because remember: the gig economy is not a single leap, but repeated leaping.

You have to learn to be a goat. If you make it too easy on yourself, you’ll never learn the necessary goat skills.

Let’s look at the four common cheats, in increasing order of importance.

The Spouse Factor

I already briefly talked about the huge effect being married or in a committed long-term relationship on leaps into the gig economy. Even if you’re currently single, this is an aspect you should wrap your head around because it may be a factor in future leaps, beyond your first one.

The example I worked out last time was for a single person (or a single-earner household). It’s much harder to model a double-income couple’s finances, and even harder if you have kids. But there’s an upside to that complexity: a double-income couple can generally get by on a single income almost indefinitely with sufficiently aggressive austerities.

Why? Because people tend to marry or partner-up within their own economic class, and even if one spouse earns much more, the lifestyle tends to be baseline affordable by one alone. At least for a while. You may have to slum it out in the bottom of your social class or move down a rung, but you’ll live.

But as I noted in previous parts, getting married solely to enable gig economy participation is a terrible idea. It’s actually kinda like getting married to get a green card or visa.

In both cases, it can be a great bit of free upside if you want to get married anyway, but a fatal flaw in the plan if you don’t.

And while a financially stable partner can be a great asset, you also have to be on the lookout for the possibility that both of you might have to make leaps at about the same time. This is likely beyond random chance. To make your leap work out, you might have to do something like move to a cheaper city, which might force a complementary leap for your partner too.

In my case, my wife quit her job within a couple of months of me making my leap, in part because of conditions created by my move. She did get a new one shortly after, but for a brief period, we were in a pretty dicey situation.

But with all those caveats in place, if you are married, that fact can either be a huge strategic advantage or a major liability (amounting to divorce-grade stress) depending on how the two of you pool your strategic options. The advantages can range from the small but important things (like switching health insurance to getting a lease on the strength of your partner’s income) to big ones like managing a long ramping period of lowered income.

Even if your partner does not work, they will likely be playing a major role playing defense. As earner, you play offense and bring in the money. But managing a household budget on a volatile gig income, especially during a ramp phase, is vastly more complex than managing it on a paycheck. Everything from strategic prioritization of spending to being very savvy about sales and coupons, is worth real money. If your non-working partner has the right mindset for playing defense, they may be able to squeeze $1.50 – $2.00 in value out of every $1 you bring in. They may be able to basically sustain the same lifestyle you were used to, at a steep discount, simply by being smarter about spending money. A good defense partner is a major force multiplier.

You could do this for yourself of course, but remember, even cycle of brain time you spend playing defense, you’re not playing offense, so it is hugely valuable to have somebody else take care of that, allowing you to focus on the topline rather than the bottomline. Also, in my experience, playing offense and playing defense require very different mindsets that are rarely found in the same person, but are often found in a couple.

And finally, don’t forget: your partner is likely going to be one of the only sources of skills and support you might need that you don’t have to pay for with cash upfront. Chances are, they will not be actually interested in doing things you need done, and might not be particularly good at it, but they will likely do it anyway to support you, while you spin up the means to pay for the services from external sources. Your partner might end up as your unpaid book-keeper, web designer, spreadsheet wrangler, or copyeditor. And you will likely be reciprocating in the future, underwriting their risks.

The great thing is, partners who support each other through leaps into free agency will likely grow together strongly as couples and the relationship will benefit. After eldercare and parenting, it’s probably the richest shared growth experience you can have in a marriage. Of course, handled wrong, it can end in disaster, full of mutual resentment.

So factor in those options in making your plans. It is up to you whether your partner becomes your secret weapon or someone who weighs you down and turns the leap into a crash. To enjoy the former rather than suffer the latter, you must make them a full partner in your leap. A part of the solution rather than a part of the problem. If you cannot, then you must rethink either the leap or the relationship.

The Parent Factor

Even if you’re quite old, chances are, your parents can help in at least a small way. They may be able to give you some money outright. Or you may be able to temporarily live with them. Or they may be able to co-sign an apartment lease with you if you can’t show enough proof of income.

One particularly tough case I heard of was from a young Lyft driver, a Filipino immigrant. He was driving Lyft because his wife had died, leaving him to care for a young infant by himself. He had to quit his job in security work, which did not allow him the flexibility to handle childcare, and had to make things work another way. So he moved in with his mother-in-law, and she let him use her car to make money driving for Lyft, while she handled some of the childcare. He was taking ESL and computer classes at night to level up into something better.

That’s a pretty rough leap into the gig economy. One that could have gone far worse without a parent factor.

Don’t be snobby about parental support. Your parents’ generation probably didn’t have to try making it en masse in the gig economy, so give yourself a break, courtesy your parents (or in-laws), if you can. Inter-generational wealth transfer is a major dynamic in civilized life, and most parents are more than willing to help as much as they are able. Historically, parents in the US helped out their children via enabling early home ownership (for example by helping with a down payment). Helping you launch a gig economy career is the same sort of thing.

Of course not all parents are great parents, and support might come with psychological strings attached and patterns of abusive gaslighting. Be wary of disempowering false narratives, snide remarks about “getting a real job” and “when I was your age, XYZ” (especially if you’re leaping into the creative or artistic side of the gig economy), and general undermining of what you’re doing. And be aware that this is something parents can do unconsciously, without intending to, while still sincerely believing they’re being loving and supportive.

It’s not actually a strategic cheat if you have to pay for material support with your mental health.

(This risk of undermining is present in the spouse factor too, but is often easier to manage, in part because you choose your partner, but not your parents.)

Transient Cost-Down

In our leap risk model, we came up with a risk estimate based on the assumption that lifestyle would remain constant.

Chances are, you won’t maintain the lifestyle, but will be able to execute a planned, transient lifestyle cost-down with little to no loss of living standard. Moving to a cheaper apartment in a cheaper city is often the biggest piece of the cost-down puzzle. If you nail that, the rest falls into place. If you screw that up, other economies may not add up to enough.

If you’re single and have a particularly mobile gig economy strategy, moving overseas to a cheaper operating location is an extreme version of this cost-down move. That playbook has been done to death, so I won’t belabor it.

When I quit, we landed in Las Vegas because my in-laws have a home there they leave vacant anyway during the summers. For six months, we paid them a small rent that was 1/5 our DC rent, a sweet deal for both sides. Then we moved in to an apartment that was 1/3 the cost of our apartment in the Washington, DC area. That was a BIG cheat for a while (a combination parent cheat and cost-down cheat). When we moved to Seattle a year later, we returned to paying roughly DC-level rents. But the Vegas leg of my ramping period was a crucial strategic cheat. I estimate it was worth nearly $35,000 in saved rent alone, relative to our DC or Seattle lifestyle. We basically did a cost-of-living gravity slingshot through Las Vegas, between east and west coasts.

Be careful though: it’s easy to end up fetishizing frugal living (especially if both members of a couple are better at playing defense than offense) and letting the transient cost-down turn permanent. It’s fine if that’s what you were aiming for all along, and there are websites and mailing lists out there to help you with that. But here at the Art of Gig, we are solving for a non-minimalist, non-spartan lifestyle: just on your own terms rather than those of a paycheck employer.

If you are in the US, health insurance can be another big shock if you’ve never paid for fully loaded healthcare. The cost of COBRA (opt-in continuation of employer health insurance up to 18 months after quitting a job) or ACA (Obamacare) may be between 3x-5x the payroll deduction you’re used to. So you may have to make cuts in other areas to maintain the same or somewhat degraded healthcare.

Other countries mostly have more sane and gig-economy-friendly healthcare systems, but have other headaches. No country in the world is entirely friendly to free agency. We live in a world designed around paychecks, so understand the differences that makes to the cost of living, and plan your cost-down accordingly.

A transient cost-down is a non-trivial bit of planning, so don’t wing it. If you don’t have at least a couple of spreadsheets going to figure it out, you’re doing it wrong.

Exit Conditions

The biggest cheat in making a successful leap? It isn’t when or where you leap, but what you leap with.

What are your assets? What are holding in that big figurative bundle in your arms when you make the leap?

The things in that bundle constitute your exit conditions. This is one cheat card you MUST play. The other things can be optional or may not even be available to you, but exit conditions are something you can always design at least a little bit.

The worst exit conditions are: getting blindsided by being laid off or fired with no severance, when you are under immense cash flow pressure or debt, perhaps dealing with family emergencies, and being forced to make the leap empty-handed. Good outcomes are unlikely there, but if you’re ever in that situation, I wish you luck with it.

But if you can do better than that, and not exit empty-handed, your chances improve dramatically.

Some exit conditions are what I think of as low-cunning exit conditions.

-

If you can time your first leap from a job at an old, declining company with a voluntary-retirement scheme, sweet. Grab that exit condition with both hands.

-

If layoffs are being planned, with generous severance packages, and you can maneuver to be on the list, go for it. You may not be one of the people they want to lose, but if they have to meet specific headcount cut targets, they’ll be open to it.

-

If you can exercise good employee perks, like getting subsidized software, just before you leave, do so. If your employer is folding and you get first shot at snagging used assets for free or cheap (like office furniture or valuable bits of intellectual property), go for it.

-

If you have to wait a few months for some stock options or RSUs to vest, wait (but not too long: I walked away from a bunch because the vesting horizon was too far out).

-

If you can get a new, cheaper apartment lease on the strength of your paycheck job just before you quit, do so.

Just be careful: don’t let low cunning exit-condition engineering turn into unprincipled or illegal behaviors. A typical gray-area case is “stealing” clients. You may be bound by a non-compete agreement, in which case it might be outright illegal. Even if it isn’t illegal, it may cost you in burned bridges and relationships, and reputational damage as people tag you as someone who pulls that sort of jerk move. Even if you are willing to take that damage, it might just be a shitty thing to do in that context to other people who don’t deserve it.

But there are also situations where taking clients from a job with you is both a norm in that industry, and the best deal for all parties concerned. Just be thoughtful and avoid hurting others in navigating this sort of thing.

Your main focus, however, should be on high-cunning exit conditions. That’s the real test of your imagination.

The best high-cunning exit condition is one in which you’ve created a live asset, out in the open, that can be turned into a viable foundation for a gig economy business with the flip of a switch. In my case, all it took to flip the switch was a post declaring I was going free-agent, and I instantly had a flood of live goodwill and support flowing towards me (including some sponsorship money, and a lead for what turned into a big gig a year later).

Throw-a-switch leap assets are of three major kinds.

-

Marketing assets like a blog or newsletter where you can start to look for and create opportunities. I had both (the list, Be Slightly Evil, is now wound down, but available as an ebook).

-

Product assets that can be turned into a money-making thing on Day 1. I had a nearly complete book that I was able to finish and put up for sale within a month of quitting. Instant spike of cash flow right when it was most useful.

-

Live, hot leads that can be converted to starter gigs before you quit. I had 2 consulting gigs and a writing gig lined up a month before I quit. They didn’t amount to much, but having any cashflow going was a big deal.

Interesting point about the book: it was a hidden exit condition for me because I was quitting Xerox, where I’d learned a shit ton about print-on-demand economics and the publishing industry. So I was able to self-publish my book in the most efficient, highest-margin way possible, and make serious money off it.

Book publishing is great for reputation, but not generally a good way to make money unless you do it yourself and know what you’re doing. In my case, I did know what I was doing, so the book was a significant chunk of my income throughout my ramp period, and still continues to make decent money today, 8 years later.

So keep a particular look out for this kind of hidden exit condition too: valuable knowledge or skills you’ve acquired in the run up to the leap that you can deploy in ways most people cannot.

Putting it Together

So that’s it for the four major cheat cards, plus any others you have in your deck to play.

Put it all together, lay it all out on the table in front of you.

Stare hard at what you have.

Somewhere in there lies a cunning plan that can cover for your leap risk deficit.

Somewhere in there is tens to hundreds of thousands of dollars in risk mitigation value. Hard, financial, cover-the-rent value, not vague soft-assets value.

Somewhere in there is the key to leaping successfully versus crashing and burning.

If you haven’t yet made the leap, kudos for starting to think about it. Take a deep breath. Even with all the preparation in the world, it’s going to be something of a shock to your system. You will gasp for breath. Your diving reflex will be activated, figuratively speaking.

If you’ve already taken your first leap and survived, congrats. As you’ve no doubt already learned, there are no medals. Employees get employee-of-the-month awards. Startup founders get flattering media coverage and awards at conferences with pitch contests.

But there are no prizes for making a successful leap into the gig economy.

All you win is the opportunity to leap yet again. And again. And again. The reward for leaping is getting started on a learning curve that makes you better at leaping, putting you in touch with your inner goat.

The first leap into free agency and gig work takes a lot of nerve and imagination, which is why most people get involuntarily dumped into it involuntarily, via layoffs or firings, with a high chance of crashing and burning, rather than making the leap deliberately, on their own terms, with vastly better outcomes.

The nerve part lies in making the leap without having a complete answer to the question of how you’re going to make it work.

The imagination part likes in pulling together the minimum viable cunning needed to make it work, using the cheat cards you have available to you.

In these last 3 articles, I’ve outlined a basic approach to taking your first leap. Together, the ground we’ve covered so far constitute what you might call the outer-game of leaping. All the practical stuff.

In the next part, we’ll cover what I think of as the inner game: preparing your mindset and mental models for leap conditions. The really practical stuff.