In the last 3 weeks, we’ve explored the anatomy of your first leap into the gig economy, understanding leap risk, and mitigating that risk with minimum viable cunning. Together, these topics cover what you might call the outer game of gigwork. The practical stuff.

Continuing this 101 series, this time, I want to tackle what I think of as the inner game of gigwork. The even more practical stuff. The inner work you need to do to ensure your new life is a more enriching, high-agency life that allows you to be more fully human than the life you’re leaving (or contemplating leaving) behind. Ironically, the key to doing this is seeing yourself as more of a robot.

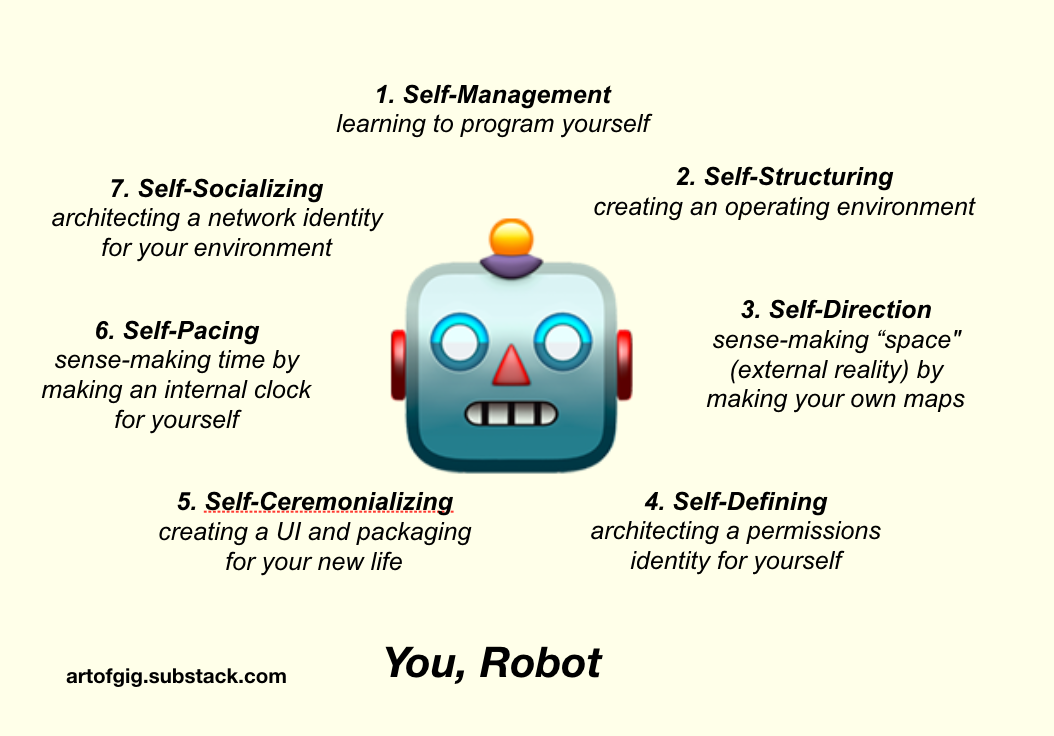

You, Robot

If a job is a simple plastic mask that hides the “real you” that comes out on evenings and weekends, a gigwork identity is an entire robot suit that allows you to express the real you. Lifestyle design is robot design.

Weird, huh? It’s the paradox of the inner game.

The more you can get comfortable in a robotic skin (for a precise sense of robotic that I’ll get to), the more human you can be. The more you resist and hold on to an egoistic sense of your own humanity, the more you’ll be reduced by circumstances to a low-agency Sturm und Drang precious-snowflake zombie controlled by the environment. In the economic outer space that is the gig economy, your robot suit is also a space suit that allows you to survive. Your choice of personas, on the surface, can seem like it’s between being a human non-playable character (NPC) or a high-agency robot character.

The key to unraveling the paradox is understanding that in the paycheck economy you’re already a robot. In the gig economy, you just have to own that fact. And if you own it well, you’ll appear more intensely human to others, the opposite of robotic.

In the gig economy, you’re just insourcing a lot of the robotic aspects of your being that were previously embedded in your workplace environment, and now have to be part of your life environment. In both cases, what they do is create a container for your squishy, messy, human psyche.

In the process of in-sourcing, you’ll be personalizing and customizing to yourself, so you’ll be more free to express yourself. Recognizing this is what dissolves the paradox.

To extend our robots-spacesuits analogy, paycheck employees are also robots. They just don’t realize it because their robot suit is a large shared spaceship containing a lot of people in a single life-support environmental system. The interior fosters an illusion of greater humanity than they actually possess. Being in a robot space-suit outside simply brings that reality so close to you, the illusion breaks. But your space-suit is still more human-shaped than the spaceship.

Inner Game vs. Outer Game

The title of this post, btw, is a hat-tip to an excellent book, Timothy Gallway’s Inner Game of Tennis, which is not particularly directly relevant to our subject matter here, but is a generally good read on developing a creative mindset. It too has a curiously robot-design approach to its subject. Turns out, the key to getting into a zen-like mindset while playing tennis has to do with short-circuiting your ego so you can relate to yourself as a sensorimotor machine that learns and enacts physical behaviors in specific ways.

The inner game of gigwork is much simpler than the outer game, but much harder.

The outer game has a lot of messy and complicated details. A lot of logical puzzles to figure out, non-trivial budget arithmetic, and timing and strategy challenges to solve.

But if you’re moderately smart, none of it is actually hard, just tedious.

The math is not genius-level math. The chess-like strategy elements do not require grandmaster-level skill to work out and play out. The complicated details are more like Ikea furniture assembly than neurosurgery. And none of it requires extreme precision. So you can kinda half-ass a lot of it and figure it out as you go along.

The outer game is forgiving so long as you’re paying attention and thinking and willing to change what you’re doing as you learn.

The inner game though, despite being much simpler in terms of number of moving parts, is really hard. And it is less forgiving. If you manage your psyche wrong through a critical period, it might be the end.

The Case for Flying Blind

Preparing for the inner game is preparing for the evolution of your own psyche through the first few years as you ramp into the gig economy. It is predicting your own emotional reactions and preparing yourself to regulate them in helpful ways. You can’t tell how you’ll react to your first serious cashflow panic, but with the right inner-game disciplines in place, it is more likely to be a good reaction.

But before I outline that preparation process, I want to touch on the case for not preparing. Unlike the outer game, where underpreparation has clear risks and downsides, in the inner game, the benefits of preparing versus not preparing are less clear.

Why? The inner game is hard enough that you could argue the best way to tackle it is to not even realize how hard it is before diving in, and then working it all out under live fire conditions. Then you can look back and marvel at your own survival.

There’s a certain gonzo poetry to that kind of outcome: clueless newbies not knowing a problem is impossible according to more experienced people, and solving it anyway. It’s the stuff of legend.

This approach might even lead to better results sometimes. If you don’t read books about the gig economy or newsletters like this one, which try to prepare you for what you’re getting yourself into, you might pull off some inspired blank-sheet creativity.

That said, I do think survivorship bias in the narratives of these survivors tends to blind us to the fates of those who don’t make it, and perhaps might have with a little bit more conscious mental preparation.

So on balance, I think it is better to look ahead at what to expect for your inner journey. You might end up doing things a little less imaginatively, but you lower your risk of not making it. It’s a worthwhile trade-off.

A possible outcome of going through such mental self-preparation is that you might decide you’re not in fact, psychologically up to the challenge, reassess the true value of a paycheck job, and decide that’s a better fit for you after all.

And that’s okay. That’s great. The more you consciously choose the roles you’re cast into, the better you fit them. If the only thing I achieve through this 101 series is making some of you happier about your jobs and more content to stay in them, that would be a good outcome.

But a better outcome would be if more people left unsatisfying paycheck jobs for more satisfying gig economy careers, and did it well enough to make it.

Building Robot SELF-X

Setting up to play a good inner game is, like I said, not complicated. It’s just hard.

All of the inner game can be summarized as building a SELF-X system. Where X is any kind of primarily psychological support that used to be provided for you by coworkers, managers, or leaders in an employer organization (or in the case of fresh graduates, a university campus and parental support). SELF-X is also a nice name for a robot suit.

The inner game is doing for yourself all the psychological environment maintenance work X that used to be invisibly done for you.

I’m going to lay it out for you in the form of an inventory of inner-game competency areas (or in our allegory, robot design areas) to think about and figure out.

Get your expectations straight: You won’t figure it all out at once. You’ll iterate through approaches on all these fronts as your new life comes together via trial-and-error. Don’t be a perfectionist about any of this. Just pick a starting design, and iterate from there.

I’m going to use the context of a regular job to describe all the X’s, but if you’re a student who has not worked a full-time job before, just substitute the university or school environment equivalents.

Self-management

When you are in a job, you are unaware of the extent to which you rely on other people to manage you. You take and hand out action items, you sit in meetings run according to certain protocols, you take responsibility for certain processes and systems, and so on.

In the gig-economy have to learn self-management behaviors.

Jobs come with other-management philosophies that induce behavioral “code” that then runs to accomplish the work of the organization. Some workplaces are built around annual planning and goal-setting. Others are built around corporate habits like agile development. Still others navigate via mission statements and manifestos.

All vary in how much management they do (ranging from laissez-faire to micromanagement), but trust me, all of them manage you more than you realize, and you’ll feel the management vacuum hard on Day 1.

How do you approach self-management? Think of self-management as programming yourself like a robot. This does not mean you have to robotic in a stiff sense. You can be a gonzo robot like Bender on Futurama. You can be like one of those Boston Dynamics gymnast robots. You can be like a spunky little rover on Mars. But whatever your robot persona, it needs code to run. Code that used to come from others. If you don’t give yourself code to run, you’ll sit there doing nothing.

Seems obvious, but it’s amazing how many people think being your own boss equals not having a boss. You won’t magically be a better boss for yourself than other people were. There’s a good chance you’ll be worse at it. So you still have to learn how to be a good boss to yourself.

Self-structuring

This is subtly different. Most people need a certain amount of structure in their lives (you can take a test known as the California Personality Inventory that will give you a sense of how much structure you need) and when that falls apart, they don’t do well. So you have to build structure for yourself.

Like building deliberate awareness of which Starbucks locations seem to foster what kinds of work moods for you.

Like running experimental schedules to figure out whether you tend to work in 4 hour morning bursts or all-nighters.

Like choosing whether to stock up a nice home-office or rent a desk at a coworking space or live out of a backpack.

Like choosing a computer.

If you think your job is pretty flexible, think again. There are a thousand defaults that are set for you in any job. A job doesn’t have to be industrial 9-5 to serve as a strong forcing function on the structure of your work life.

How do you self-structure? Think of self-structuring as creating an operating system around yourself.

Code needs an operating environment to run in. But unlike the self-management behavioral code you write to run the foreground of your work, the operating environment code is more likely to be assembled from multiple other sources. Your task is that of architectural selection, not construction.

Though this might involve a lot of practical decisions like notebooks and computers and desks, they are primarily decisions that affect your inner mental state. That’s why they’re part of the inner game.

Self-direction

You not only have to be managed in a job, you have to be led, which is an entirely different thing. To be managed is to be given behavioral code to run, and an operating environment to run it in. Together, these determine how you work.

To be led is to be given direction and a motivation, a why. Things to do and a reason to care.

I like A. G. Lafley’s definition of leadership as “interpreting external reality for the organization”. This is not an objective, dispassionate description, but an opinionated, emotional understanding that makes a particular direction of movement seem inevitable and philosophically necessary, rather than merely logical.

And here’s the thing: psychologically, it doesn’t matter whether a leader is good or bad, whether their “interpretation of external reality” is a powerful vision or batshit insane, or whether their direction is taking the company to the moon or over a cliff.

The mere existence of ANY default interpretation of reality and direction of movement is enough to fill the need to be led. You’ll just march along. Perhaps reluctant and grumbling, but you’ll do it.

When you go free-agent, you’re on your own for this vectoring, and people tend to do badly without a sense of direction. They tend to stall entirely, and stop moving.

As a result, one compensatory response is that free agents often fixate on what I call “free and open-source public leaders”. Charlie Munger for instance, is the de facto CEO of thousands of free agents. So are Paul Graham and Naval Ravikant. In a previous era, when the gig economy had a distinctly feminine tone to it, due to the paycheck workplace being less friendly to women, Martha Stewart and Oprah Winfrey were the de facto CEOs for many women trying to run home-based businesses in the interstices of childcare and housework.

But admirable though such public leaders may be, they are not actually your leader!

The only lasting solution is for you to become your own leader. Your own CEO. You interpret your own reality, you set your own direction. Inspired or insane, your own direction is the only one you’ll be able to follow long-term.

Think of self-directing as making and maintaining your own maps, location awareness, and movement.

Don’t underestimate how hard it is. The easy part is drawing a map, and picking a logically coherent direction to go. The hard part is doing it in a way that you’ll actually care about going in that direction enough to take step after step, indefinitely.

Orientation is more than location awareness. It is motivation. The words motivation and motive indicate an urge to movement, not merely Google Maps directions.

Self-defining

In a job, who you are is determined by your job description and responsibilities. As a typical cynical employee, you might not care about titles and status beyond their being linked to compensation and perks and resume-stuffing for your next job. But even a title you’re cynical about molds your sense of self at an unconscious level. If you say enough times to people, I am Assistant Regional Manager at Dunder-Mifflin, it becomes your self-definition. The mask becomes the person. And one of the big effects is your sense of agency is shaped by your role.

In a gig economy, you have to do that for yourself. In my case, identifying as a “sparring partner” was an important early step. Self-definition is not the same as self-classification. Things like 2x2s and taxonomies might help you self-classify, but self-definition is sort of a declaration of who you are, and in particular, how you understand your own agency.

You’re your own boss. What do you give yourself permission to do? What rules that you used to follow in a paycheck job do you now break? What new rules do you now follow that you didn’t before?

In our robot allegory, self-definition is the act of constructing a permissions architecture around your own behaviors.

Think Asimov’s 3 Laws of Robotics. They aren’t “personal brands” or logos. But they strongly define the nature of Asimovian robots. What are the laws of You, Robot? What does “doing the right thing” mean to you? What does “doing the thing right” mean to you? That’s self-definition.

Self-ceremonializing

Another thing that organizations give you is a sense of ceremonial appearance. A way you appear to others in the context of work. This is again far more important than you might think.

So go ahead, order those business cards even if you have nobody to give them out to. Set up a website even if you have only uninspired boilerplate to put on it right now. Spend time cleaning up your LinkedIn. Have a friend take a couple of good headshots. Change your Twitter headline. Put your incorporation certificate up on the wall of your home office even though nobody will ever come by to check.

But don’t go overboard into absurdity. Don’t give yourself awards or silly titles even ironically. It’s a waste of mental energy, and drains seriousness.

The point of self-ceremonialization is to close a sensory-cues feedback loop to manage your psyche. Think of it as setting up mirrors all around yourself, not out of vanity, but to reinforce a way of being.

Some of this will happen naturally through self-structuring. An in-tray on your home office desk is both a ceremonial location for papers, and a cue to work on them. A Dilbert cartoon on a corkboard though, might not have any obvious cueing function for an instrumental behavior. It might just be an attitude set-point reminder, or a reminder of some philosophical principle. That’s part of the pure ceremony. The self-structured environment will get the work done, but it will likely not have the right emotional contours or signal the right priorities. Self-ceremonialization distorts the reality you inhabit in useful ways.

Think of it as taking the orienteering logic of self-direction, and the permissions architecture of self-definition, and using them to distort how the operating environment appears to you. Some things will loom larger, other things will shrink. Some things will be set up to be easier to do. Other things will be set up with guardrails to make them harder to do.

The point is to make your new life emotionally real for yourself, by setting up your own reality-distortion field. Think of self-ceremonializing as creating an effective UI for your new life.

Self-pacing

In a job, you have a reference pace, or workplace tempo. You define your own pace with reference to it. Do you go with the flow? Do you try to overtake others? Do you pace-set for others? Do you disrupt the flow?

But in the gig economy, there is no default reference stream of activity for you to define your own pace against. Think about it. When you start, perhaps you have one client in Silicon Valley going crazy fast, and another in a sleepy Midwestern town ambling along leisurely. Which one do you use as a reference?

Any simplistic reference-pacing will lead to schizophrenia. You have to look inwards to develop your own sense of pace, relative to your own life. You have to create a sort of time zone around yourself, just as ships out on the ocean have a “shipboard time” that is systematically set and reset as the ship sails across different longitudes.

How quickly do you respond to client emails?

What does it mean when you promise someone something “as soon as possible”.

What does “I’ll get to it this week” actually mean when you say it? Does it mean the same thing when you say it to different clients?

In our robot allegory, self-pacing is about sense-making in time via construction of an internal clock, now that you don’t have an external one from a workplace to drive you. It is actually another aspect of self-direction, the temporal dimension of leadership, but I like to break it out because it is a uniquely critical aspect.

The difference between armchair strategy and non-armchair live action often boils down to a ticking clock. The clock is the bridge between strategy and execution.

What is the right pace for the gig economy? It is almost always “faster than you are comfortable with”. The environment will tempt you to its own pace, and as you move across contexts, you might start behaving like a temporal chameleon, relaxing with relaxed clients, going neurotic with neurotic clients. This is the dark side of “being on the clock” in metering/billing terms. If your clock is no more than the sum of billing clocks in your various gigs, you’ve come temporally undone.

Don’t come temporally undone. Build an inner clock. Set your own pace with reference to the state of your own inner game.

One of the best ways to do this is to build up a compounding asset over time. Your internal clock is measurable by the runway you’ve laid out for yourself for that asset to gain value. For me, it’s been writing about business topics. It’s only a fraction of my writing, but it’s obvious when I’m not moving at a decent clip: I don’t have interesting new things to say on business topics. You could almost measure the pace of my consulting life by my rate of publishing decent business-related articles.

Self-Socializing

The final part of your inner game set-up is other people.

In a job, there are typically cultural structures in place to socialize you into a role, and keep you there, primarily via mediated interactions with other people. Happy hours, seminars etc. In the gig economy, you have to do this to yourself. Hell is always other people, but as a gig-worker you get to design your own hell. Make up a mix of social activities to suit your personality. Some mix of meetups, lunches with friends, and sessions at Starbucks should do the trick.

You have to set up the social structure and cultural rhythms you need to function. That much is easy and obvious.

The hard part of self-socializing is understanding how you depend on other people, who they are, and the extent to which they recognize the role they play in your new life, and then rearranging things if they seem to be unhealthy and limiting rather than healthy and enabling.

In a paycheck job, you don’t have much control over who’s in your socialization environment. In the gig economy you do.

You can more easily cut out people who drag you down, and add people who lift you up. But it doesn’t happen automatically. You have to exercise that capability to unlock a lot of the benefits of gigwork. But you’ll be tempted to add/subtract exactly the wrong sort of people, creating a self-defeating social environment for yourself.

In our robot allegory, self-socializing is architecting a network-identity for your environment.

Putting it Together

Let’s summarize. The inner game of gigwork is about constructing a robot suit for yourself, by insourcing things that used to be done for you, which help you manage your psyche as you figure out how to fend for yourself.

There are 7 basic areas of design to think about, as illustrated in the graphic at the top of this issue.

-

Self-Management: Learning to program yourself

-

Self-Structuring: Creating an operating environment

-

Self-Direction: Sense-making “space” (external reality) by making your own maps

-

Self-Defining: Architecting a permissions identity for yourself

-

Self-Ceremonializing: Creating a UI and packaging for your new life

-

Self-Pacing: Sense-making time by making an internal clock for yourself

-

Self-Socializing: Architecting a network identity for your social environment

This is a to-do list and a set of starter cues, with a hopefully helpful robot-suit allegory. I’m not going to tell you how to set up your inner game.

There’s a lot of good and bad advice for all of these areas of design focus out there. How you put your mindset together by putting these robotic parts together, and how you breathe life into it by putting it on, is actually your first big challenge in the gig economy.

There’s a holistic test for if it’s working though.

If you’ve designed your robot suit right, it should become almost invisible to both you and people who see you operating. You should feel a sense of freedom and control from the inside, and from the outside, exude a sense of intuitive agency. People may see you fumbling and stumbling. They may see you gracelessly working through trial-and-error experimentation. But they should get a sense that you know what you’re doing.

If your robot suit is visible (in the form of formulaic behaviors that mark you as as an easily identified “type” for instance, or as a “personal brand” robot that is put together with preternatural poise), it is a badly designed robot suit. Or the suit has become your master, like Doc. Ock’s AI arms in Spider-Man. Many free agents in the internet marketing world unfortunately come across as bad robots, their humanity subordinated to a bad inner game that has pwned them. They look like characters out of a sketch-comedy show rather than people. Parodies of themselves.

On the other hand, if you seem painfully all-too-human, but your behaviors seem whiny, overly vulnerable, and low-agency, you haven’t in-sourced enough of your psychological support environment yet. Like a starving artist who produces no art, but is very loudly human about it, playing the part of a sensitive soul being tossed about by a cruel world. No, that’s as bad as being a formulaic brand-bot. That is performative learned helplessness. That’s being a Sturm und Drang precious-snowflake zombie (I know I already said that, but I like that artistic slur so much, I had to repeat it ICYMI the first time).

Avoid both failure patterns. Get your inner game going right. Invisible suit, visible performance of real agency. Be a live player, not a dead player.

With this post, we’ve covered all the 101 content I wanted to in this series, but it feels like this could use some pulling together, so I’ll attempt a summary post next week, with suggestions for how to pull it all together without getting overwhelmed.